The Fornicatorum was immovably solid, having been fashioned from heavy Amazon timbers and wide sturdy side panels made of dense ply. It was fiercely resistant to the application of cemented shells. Once I gave the cabinet a kick in some adolescent rage, to find the stylus played on without the anticipated skittering across the vinyl. Several tesserae were displaced and stuck back with denture plastic before my father got home. The Fornicatorum played another part in my life, suggesting further evidence of a suspected Solipsism. I had just just started to play my new 45rpm single of Ray Charles’ Hit the Road Jack, when first reports reached Watford of the assassination of John Kennedy.

One wooden book case in the Lounge contained reading matter for the family ; The European Guide to Wines; Readers’ Digest Condensed Books (Agatha Christie and Neville Shute); a Road Atlas of the United Kingdom lacking several pages and an illustrated edition of the Kama Sutra, all presented by friends of my parents at Birthdays and Christmas. My personal discovery of books is treated elsewhere.

Over the fireplace was a giant sheet of framed hardboard depicting a Purgatorial Landscape with a sly Boschian face, crowned with a sparking tiara, balefully surveying the devastation all around, and, no doubt, also deploring the rising tide of decorative molluscs in the room beyond the frame. Seen from a certain angle you could see that I had used a handful of nutty slack to achieve a barren texture for the foreground swamp. At uneasy sherry parties for neighbours I would often find my proud but uneasy parents pointing at me across the room as the creator of this solemn image of Doom whose pessimism was mitigated solely by the presence of anecdotal coal dust.

My key youthful access to images of art was in the back office of the art room at Watford Grammar School for Boys, where a row largely disappointing Phaidon picture books of the Great Masters were on the lowest shelf with cheap paperback editions of Nikolaus Pevsner and Ernst Gombrich above. I still have a few of post war Phaidon monographs where Botticelli, Van Gogh and Cosimo appear in drab colour tipped in plates sparingly distributed between solid blocks of fuzzy sepia reproductions.

A memorable step was my purchase of Robert Descharnes’ monograph on The World of Salvador Dali (1962) , after going without lunches for the term. It was a sharp spectacle I remember, scrutinising it closely with Phil Beard. We had aspirations to be Hertfordhsire’s Go-To thinkers for Surrealism. Our hand written translation of Les Chants des Maldoror , from the French original smuggled back from Paris by Phil in his underpants, brought us much peer admiration. until Guy Wernham’s translation revealed that there was not a single sentence we had translated accurately. How Surreal is that? we asked. After we left secondary education, Phil and I went up to London at the weekends and get to see real art.

Examining art school candidates at interview I bear in mind my own callow tastes and early fascination with Dali in particular. In the sixth form, I was entrusted with a long expanse of wall surface in the art room over a window by Mr Smith and for a mural painted with a hybrid of Dali and Douanier Rousseau. There was a centrepiece of a telephone with the number “Dali 54842” , a direct use of my parents’ Co-Op divvy number, combined with the anagram of Dali, a tricksiness that was purely subconscious but in advance of discovering a much better anagram for the Spanish Master, Avida Dollars (Hungry for Dollars).

Despite A level and Degrees undertaken, Art did not attract as a theoretical speculation, an exercise in the history of ideas. The basic appeal was that images themselves presented propositions without the necessary addition of spoken or written language. In my childhood, unlike so many of my peers, I always shied away from arguments with whoever, friends, relatives, teachers. This was partly good manners and partly cowardice. Perhaps it was laziness in that I found the sharpening of clear ideas and structuring of responses arduous. Much better was revealing an image, like playing a card, supplemented by a succeeding image and so on. Presenting the image sequence was so much more an act of theatre.

“ That this house regards Buddy Holly as symbol of the decline of the Musical Culture of the Anglo Saxon race…” My responses to anticipated defeat in the ensuing debate would fall into two stages, Sneering, followed by Extreme Violence. In retrospect I was not so much interested in the History of Art (invaded and colonised after 1965 by exiles from other disciplines) but how we make art, and later, how we as consumers or assessors, judge art in terms of success and failure. I found that my best apercus (as John Gage called them) came when without prior deliberation, Often I found myself talking aloud without preparatory notes in lectures in the format of an internal dialogue overheard. My sudden reference to Santa Claus’ lower lip in a permanent state of dampness was unplanned but nevertheless has lived with my audience to this day, although never satisfactorily explained.

There are several factors that encouraged this concentration on the image and its making, rather than its theoretical understanding of its larger context. At UEA we were taught to approach art history in Morellian terms. Was this a genuine Piero de Cosimo? The artist may in the distant past have revealed his identity more in the depiction of smaller details such as ears and finger nails rather than the larger design. That this was, in 1965, at the service of the Art Market seeking to authenticate its speculative purchases, seemed disreputable at the time and proved a pointless skill with art students.

At UEA, students followed the Comparative Method, familiar to any Courtauld student. It was an entertaining exercise like Pelmanism or playing dominoes. On the left screen is a page from the Codex Ionicus of the stoning of Stephen and on the right the same subject from an illuminated manuscript from Crete. Completed artwork, say Seurat’s Grand Jatte, could be on one screen, and a range of studies on the right, a spectacle getting to the heart of the working process. Powerpoint was a distant dream. Even nightmare.

I had my fair share of guilty pleasures in 1965 and beyond. In my Finals I made huge claims for that late Pre Raphaelite book illustrator Robert Anning Bell, a tea towel artist at his best. I am lucky that at all stages in my trajectory I was able to compare notes with Phil who was scrupulous in his tastes, faultless in selection, and ruthless in exposing tosh. I found often that we were discovering the same clusters of images at the same time, and could devise shorthand methods of showing our mutual admiration for the artist. The fierce struggles over ideas were not for us. It saved so much time. We only had to say Edward Hopper and Gustave Caillebotte and a set of cherished understandings fell into place.

My first year at Norwich in the School of Fine Arts and Music, starting October 1965 was the first year of the course. I was interviewed by the Professor of English and Shakespearian scholar, Nick Brooke and discussions were of a gentle, even whimsical cast that touched on abortion and cooking. After I had been offered a place by Norwich, and having rejected a place at Sussex to study English with David Daiches, the University of East Anglia appointed our first teachers, Peter Lasko and Andrew Martindale, the former an ebullient maverick with a glass eye, fresh from the British Museum, the latter from the Courtauld, the son of an Archdeacon of Bombay. In Casting Circles Lasko would be played by Simon Russell Beale, and Martindale by John Le Mesurer. When I foul-mouthed the locals during an interview on Anglia TV, Peter watched my back and saw off sniffy old Frank Thistlethwaite, the Vice Chancellor, who wanted me out. On the first day at University. Frank greeted the new bugs with a clear proposition that undergraduates were only there to support academic research at a higher, a much higher, level. And that we had to buy meal tickets for the canteen.

Until July 1966 I studied medieval art and architecture, my first paper being a reconstruction of Norwich cathedral before the 12th century fire, using imagination and an expanding measure, Later in the year I was encouraged to scrutinise illuminated manuscripts. Solander boxes of green cards bearing duplicate photographs from the Courtauld were lined up on metal shelving. Michael Brandon Jones and Stella Shackle seemed to labour day and night to establish our own Norwich photo resource, while Nora and Linda were responsible for the Slide Library. Linda was married to Mel Clark at the Art School. Trevor Fawcett, appointed Librarian of the Art and Music collection greeted us with a table of books over which he raised his arms. “This it “ he said, “this is your section of the library.” There was however a rich library of periodicals and journals; titles I had never heard of such as the Journal of Public Opinion and the Gentleman’s Magazine. Peter Lasko saw to it we had the regulation yardage of Burlington, Apollo and the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld.

I remember trips to outside collections, at the John Innes Institute and their collection of botanical books, and to Felbrigg to be shown around by the antiquary Ketton Cremer (shortly to leave his working library to the Library).

Andrew Martindale was my Personal Tutor, and I treasure his reflection during one tutorial, that “Women were bloody funny creatures.” I could never look at his wife Jane, a considerable scholar herself, without remembering this poignant reflection and wondered what could have occasioned it.

We associated Andrew with his popular book The Rise of the Artist (1972) and it was this rather than his definitive study of Mantegna that caused merry chuckles among the more salacious of colleagues and students. John Gage was always on the lookout for a good double entendre. I remember his equal delight in discovering the existence of the Victorian periodical Once a Week.

When John Gage and Alastair Grieve were appointed for our second year , our visual vocabulary was expanded to the Romantic and Victorian eras. John Gage’s lectures were stimulating, esoteric and curiously maddening. His books proved to have the same effect on me; Colour in Turner (1969) for example, where the footnotes were the soaring nave of the structure leading to the side chapel of the central arguments. I admired his ability to deliver quotes in a range of European languages without translations. He invited the German scholar Helmut Borsch-Supan Horst Supan to give a lecture on Caspar David Friedrich, then little known in the UK. They had clearly enjoyed the best of hospitality at lunch, John explained that Helmut’s spoken English required a translater and he proposed to fill that role. After 15 minutes John interjected that the speaker was appearing to be explaining the cut of his trousers, Obviously a mis-translation.

From John I learnt much about landscape painting. My first paper for him was intended to be a stylistic survey of "The Norwich School", which I had misheard as "The Norwich Society". I spent a month going through the annual exhibition catalogues at the Norwich Reference Library but was awarded an A grade for my originality in paper, and my wilful regard of what was expected of me. In my Finals papers I remember with fondness John’s identifiable contribution was “Colour Circles” no less, nor more – no question, and no proposition. After my PhD John sent remarkable tasks my way, such as the G.F.Watts show at the Whitechapel (1974), the British Painting show at Munich for the British Council. You’ll find a separate obituary with illustration elsewhere in my website.

I have learnt to call the student group a cohort but this word scarcely covers the the range of new Fine Art and Music Students at Norwich. We were all were delightful and hard working. Lasko pushed us to the limits as he had no experience delivering and testing a syllabus and a curriculum. One student, Alison, in the Music Department did not complete the first year because of overwork.

As I remember them. Heather Parry and Valerie Harrison. Bridget Wilkins, Vanessa Watson, Ben Johnson, John Everett (my best man). Kathy Jenkins , Anne Foster, Michael Servaes, Timothy Raiment and Johnny Barclay. In the Music department, Graham (surname forgotten) John Trevitt and Michael Z Lloyd. Johnny took the reverse journey to mine, beginning in Art History and making his way to Law. Except he was supremely accomplished in both.

Alastair’s teaching suited me more, a close scrutiny of visual narratives in Victorian art and illustration with a modicum of understanding of the social context. Given the wealth of book shops in Norwich it was possible to find the Moxon Tennyson or volumes of Once a Week for shillings. In a Christmas sale at the Norfolk and Norwich Subscription Library unwanted books including a rare pamphlet with a Cotman etching, were sold for virtually nothing. Frederick Sandys was a favourite local son and I got so keen as to view the collection of Sandys portraits in the collection of the Colman Family., building on examples in the Castle Museum such as the poignant Autumn. My inititives were leaked to the local free paper whose headline caused Dr.Gage to guffaw, “ Chris Mounts Exhibition”.

Fred Sandys Autumn, Castle Museum Norwich

I don't think I encountered subsequent appointments to the department, Richard Cocke and John Onians, Eric Fernie and Alex Potts. John House arrived but I didn’t take to his ways at all. Once working at the Norwich School of Art I worked with Jane Beckett and Rosie Ind on a show for the Castle Museum, A Terrific Thing, English Art 1910-1916. This show I remember in particular for two reasons. Firstly the groundplan was designed by Rosie Ind, with a deployment of screens in the shape of a particular Vorticist painting (perhaps Frederick Etchells). At the last minute the Castle authorities (Francis Cheetham) decided that the ten foot high screens had to be raised on stilts so that quards could spot members of the public (hopefully men) masturbating in front of the exhibits, unspeakable acts revealed by the quivering of their trouser legs. My students at the Art School and particularly Steve Nelson, worked hard that final weekend.

Secondly the van with three million pounds worth of British painting from Southampton and beyond, disappeared en route when the driver decided to take a long weekend with his girl friend.

FREDERIC LORD LEIGHTON,

In 1965 with my 2.1 I was encouraged by Peter Lasko to apply for a grant to study for a PhD award. There was a character in Dostoevsky’s The Possessed who chose a wife at random and to shock his friends. I chose to study the works of Frederic Lord Leighton, a profoundly unfashionable artist on the cusp of rediscovery in a bullish art market. Nothing I did could have made him interesting or indeed crucial to our understanding of picture making. With Alastair Grieve as supervisor. I dutifully prepared an extensive catalogue of his works and trailed my way through his stylistic development. Alan Bowness, my external examiner, objected to my attempts to sauce up the black cloth bound A4 tome with chapter headings from Henry Fielding. He unerringly identified that I had succeeded best in describing the retreat from subject matter into formalist experiments of brushwork and proportionality into the 1860’s. And to explore Leighton’s fear of mental and physical decline in old age. Like many of his contemporaries he was uneasy at the passage of Time. I think I disappointed Peter Lasko that after his efforts I didn’t turn up to my award ceremony preferring to spend the money on a box of vinyl records, and made a bonfire of my research notes and photographs as soon as I was doctored by a certificate arriving in the post. Alastair was patient and got me through. For Heide Grieve I volunteered for the WRVS and did a stint with a trolley in the Norfolk and Norwich Hospital.

Alastair and Heide originally lived in a self-initiated Corbusian house in Hingham with David Chadd in the other half. They moved into an elegant town house in Norwich inhabited with the same austere elegance. Oriole and I were round for a meal one winter's evening with Richard Shephard and his wife, whose lectures at UEA were wonderful, "Kafka was Guilty" being my favourite. I marveled at his chutzpah choosing the moment when both hosts were in the kitchen, to warm up the sitting room with not only a few logs but also the log basket. Not for nothing was Dick Shepherd a Dadaist specialist.

What had I learned about Art in the process of postgraduate research? I had enjoyed meeting curators and exploring Art Gallery basements, two sources of scandalous gossip at the dinner tables of the future. I started researching public collections at a time when unqualified librarians were let loose in collections of art works willed to the Local Authority. Even then a significant proportion of catalogued work had already disappeared or was found damp stained and mouldy. Pre-Raphaelite panel paintings were propped up against radiators, watercolours lay directly beneath leaky windows. Small pyramids of cigarette ash lay everywhere, or was it mouse turds? It was difficult to say. In the basement of a provincial basement I remember seeing a ten foot portrait military portait of a posturing Cavalry Officer on horseback, with a paint surface that slipped downwards on its fugitive asphaltum base over the edge of the frame. One tentative hoof was making for the floor.

Never mind, I was told by a council official , our collection will survive Armageddon in a specially designed fall out shelter. The curator did confide to me later that she intended to use the facility herself rather give protection to the Herkomer portraits.

In my research period, 1968 to 1971, Leighton House and William de Morgan House, eager (and comely) researchers were often rewarded with their pick of the smaller elements in the collection. No matter how enthusiastic or glamorous I appeared, nothing of an authentic images came into my possession. Not for the first time my efforts at playing the Art Tart failed utterly.

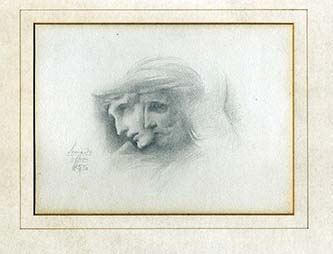

The only Leighton I acquired was this sensational pencil drawing dated 1856 after Leonardo’s Virgin and Child in the Uffizi. Jeremy Maas was a pioneer of the understanding of Victorian painting, through shows in his gallery in Cork Street, He had acquired Leighton’s Flaming June, which tempted the young Andrew Lloyd Webber into a purchase he couldn’t afford. It was to be acquired by the suitably named Ponce Museum in Puerto Rico. Before it was first shown in 1969 Maas showed me the recently acquired monumental Cymon and Iphegenia by Leighton. I loved Maas' offhand attitude to his stock. Knowledgeable but hardly in a state of awe and veneration he revealed over rum and coke how much brighter the surface became when he scrubbed it hard with half a potato. For five pounds he gave me the choice of a drawing from a sketchbook from Leighton’s studies in 1856. As a talisman it meant much to me, a touchstone of what the future president of the Royal Academy had achieved as a student/young artist.

I found Leighton’s bank accounts, and discovered how little he was earning in his later years from completed work. His own bedroom at Leighton House was spare, even austere, lined with grocer’s brown paper, a dramatic contrast to the splendours of the rest of the House, and the Arab Hall in particular. There was evidence that as a young man he joined the Masons and that the sale of Cimabue’s Madonna carried in procession through the streets of Florence to the Prince of Wales in 1855 may have reflected this affiliation. The Librarian of the main London Masonic temple denied huffily that a caricature of the artist in 1858 with his trouser leg rolled up, denoted anything at all.

My sole written account of Fred was when,at John Gage’s suggestion, I reviewed Chistopher Newall’s Lord Leighton in 1990 for the Times Literary Supplement, where in lieu of serious things to say I drew attention to how tiny was Fred at 5 foot 2 inches, with a high pitched squeaky voice and that his landscapes backgrounds had been painted for him by F.G.Cotman, then a young Norfolk painter (directly communicated to me by F.G.’s son Alec Cotman). I was not approached for a review again.

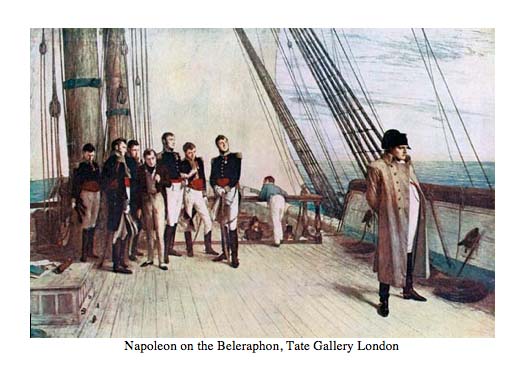

It was heartening that the Victorian masters employed an army of specialists to allow them to concentrate on the whole point of the canvas. Orchardson’s Napoleon on the Belerophon was such a joint production, combining the skills of a specialist for the perspective of the deck planks, a specialist for the sky and yet another who specialised in rigging. Orchardson was left with the figures and various expressions of the naval officers and the tiresome wistfulness of Boney.

It seemed to me incontrovertible that Leighton was gay despite the sheer weight of female pulchritude he cultivated on canvas. Lord Frederick Gower hinted darkly at skeletons in Leighton's cupboards but despite more systematic studies by scholars, no evidence came to light, I was happy to leave the field to the Ormonds, Richard and Leonee who lived near us in Hampstead. Oriole and I were invited for drinks before supper (a phrase we hadn’t previously encountered) and Oriole upset her glass of beer over their white carpet. I gave a talk on Leighton and Rossetti at the Courtauld but disappointingly the Ormonds pointedly left before I started to speak in order to be able to publish their researches without having to acknowledge anything of originality from me.They needn’t have worried. I did confirm in my mind that a collegiate attitude to Art History was a rare tendancy.

A short story by Henry James invented a character called Lord Mellifont, who was at ease, mellifluous in company, but who vanished into thin air when there was no one to listen. If this character judgment is correct it was not the most appropriate subject for a doctoral award which also seemed to dissolve a being forgotten.

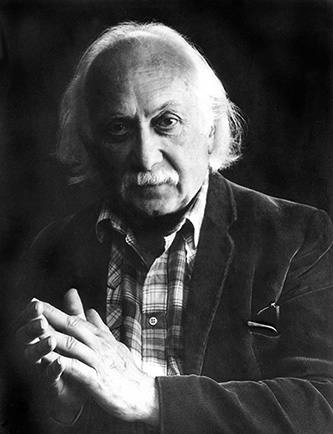

In the period between despair at the vapidities of Fred and teaching at the Norwich School of Art in 1972, I discovered whole new worlds of art in libraries and collections on show. Seeing Edward Hopper for the first time confirmed many thoughts and ideas I’d shared with Phil over the years. If Leighton induced a personal sense of indulgent foppery, and a realisation that late Victorian art had little to say to my generation, the discovery of Percy Wyndham Lewis changed my whole idea of what art and the artist could achieve.It forced me to confront my liberal tendancies with various degrees of nastiness colouring a formidable artistic talent.

THE ENEMY

The Vorticism and its Allies show at the Tate in 1974 supplementing shows I’d seen at D’Offay’s Gallery and the Victoria and Albert offered ideas and attitudes, images and objects that constantly excited and kept inviting me back to extend my interpretations and understanding. Teaching at an art school, I found everything I needed in the products and performance of the Vorticists, imagery that challenged and affronted rather than enriched the spectator,hardly transfixing the sensitive soul with its sheer Beauty.

To make the transition from contemplating Leighton’s study of the graphic possibilities of damp muslin artfully deployed on giant lumps of cotton wool, to Wyndham Lewis’ bully boy paintings and thuggish typography, was a purgative experience. I devoured what I could with no specific intent and no academic ambition, His formal vocabulary was of a set of correspondences I hadn’t encountered, passingly similar to drawings I had years ago when I couldn’t think what to draw. His representational items semed to chime well with satirical interests I had, and here was an artist, the most inventive English painter after Sickert that could write short stories, produce literary and political criticism and who could look after himself (if not other people).

It was possible to acquire first hand materials in the period before the publication of Richard Cork’s Vorticism in the First machine age, 2 volumes 1976. From a London bookshop I bought both issues of BLAST, one previously owned by Fanny Wadsworth with a failed Vorticist drawing on tracing paper tipped in. Books from Lewis’ own library were sold by Froanna including Lewis’ own copy of Hulme’s Speculations signed demurely WL on the titlepage. Froanna had commented caustically on several of the books I bought with chunky marginalia in blue broad brush e.g. “ he didn’t go himself but read about it in the Times.”

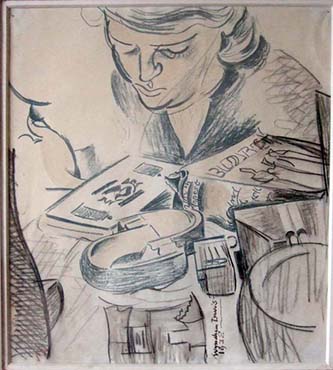

Best of all we bought Lewis’ drawing A Full Table, coloured chalks, 32 x 36 cms dated 1938 from the Mayor Gallery, a drawing that daily surrenders thoughtful allignments of forms and tones as I prepare myself for the day.

Lewis had died in 1957 but several of his coterie were still alive, Hugh Gordon Porteous, D.G.Bridson, Julian Symons, even Lewis’ widow the gentle and elegant Froanna.

I met them all and others in the first Lewis Symposium at the Tate in 1975 chaired by Symons. I had tested out my lecture on Lewis and Gustave Lebon at the University of East Anglia. At the Tate Symposium other speakers seeemed to be more inclined to the liberal left with some ingenious skating around the artist’s Fascist tendancies. I had delighted in my discovery of Lebon’s The Crowd, a study of the Popular Mind although it was difficult to square Lewis’ jagged spiky mannikins with Lebon’s jellyfish imagery. My quote from a Lewis travel book expressing his sympathy with the Action Francaise and Charles Maurras, pleased the fans who had stuck to more obvious sources . Symons asked me whether I considered Lewis to be essentially a Manicheeist. My response seemed to satisfy him, and indeed me after I found out what it meant.

From that moment onward my interpretation of Lewis’ achievement was a lens through which I viewed the world whether it was eighteenth century satire or twentieth century crowd theory, art school politics or American foreign policy.

ART SCHOOL DAYS - NORWICH

I had finished my PhD revisions and had the thing accepted. I turned down an art history job in Birmingham that involved a heavy teaching load as well as spending afternoons sticking newspaper clippings into scrap albums.

Oriole and I were living on the outskirts of the village of Hingham in Norfolk. The Course Leader of the Vocational Design Course at the Norwich School of Art, David Beaugeard lived in the village. At his dinner table I was asked if I knew anybody who could teach Graphic History to his Vocational Design students. Over the weekend I prepared booklists and talks on Graphic Processes and Print Making not having taken in that my students were studying Graphic Design . What I thought was going to be an exercise in print states and prepared grounds, turned out to be Corporate Identity and abstruse exercises in Kerning Text.

I started the following Monday and my whole direction of life changed. No longer could I contemplate the image without pondering the person who created it. Morellian scholarship in the service of the Art Trade, substantiating the attributions looked a useless facility in helping young people who were trying to understand why they were so good at creating objects and images. The correlation of Victorian illustration and poetry I had taught at the University proved of little use to twenty working class kids with low academic achivements. I introduced talking about how films work with a study of Scorcese's Taxi Driver whose narrative and garish editing suited the tastes of the Vocational Design students. The Old Masters seemed something for Christmas cards while Marcel Duchamp was more relevant for his sheer perversity. Before my first lecture on The Large Glass, the older Voc Des students took me to the pub, slipping a mickey into my Guiness that ensured a subsequent wealth of saucy anecdotes about the Great Man.

Jonathan Miller refers to a Suppository attitude to Education, That was me, and my job was to give a glaze of Culture to Shallow Practice. Students resented being presented with the conventional cultural baggage of 'Isms in painting, and glib theoretical constructs. They resented being dragged out of the studio for their weekly diet what seemed little to do with their practice. The values of Liberal Humanism held little sway with one cohort of Vocational Designers who had, in the majority, joined the Junior Wing of the National Front. They were immensely accomplished with projects they were given but lacked any academic credentials. My lectures on Post Impressionism scarcely touched the sides, but Wyndham Lewis went down a bomb. When I had the power teaching across the Art School I extended the introduction of Film Studies into the general syllabus. The Vocational Designers and Degree students seemed to flourish on a diet of violent and shocking films, reinforced when I was in a position, by tutors in Graphic Design some of the film postgraduates from Charles Barr’s courses at the University of East Anglia, – among others Peter, Pete, Leon, Margaret - spanning critical scrutiny from Gracie Fields (Margaret) to Dario Argento (Leon). Rod Brookes was finishing his PhD on Sidney Strube and added hugely to the richness of visual expertise available to students.

Hiring a TV for video projection was unusual in those quaint technological days. I even got a film budget for the projection of spooled films. The previous diet of Godard and Bunuel was supplanted de Palma and Scorcese. Word had got around and there was a full house of students from all courses (200 in the raked seating) to watch de Palma's Blow Out. I had been assured that the film was intelligent, visual and, at heart, a de-constrution of the process of film itself. No one said it started without warning with the POV of a sadistic sex killer in an ice hockey mask stalking a nurses hostel. The stabbing in the shower ended with a comic gurgle The film was the story of the search for a suitable shriek of terror. Until Travolta appeared I was in a state of high alarm, half my audience in a state of outrage or arousal at the Exploitation.

The technician responsible for film projection would add greatly to the mystification of the medium by usually showing the reels in arbitrary order. Certainly Kubrick's 2001 was transformed by the device.

In order to respond to student needs then my interests followed their enthusiasms. This was healthy in that my cultural base and visual repertoire broadened but could also include tangential issues such as sound in design and animation, careers that are commonplace today. Similarly I had every excuse to ignore the modish critical terminology of the day, structuralism, poststructuralism, tropes, and the like. One of the more cheering things said to me on a return to Norwich many years later was that I had been been well below the parapet and let the waves of theory pass me by. Bridget Wilkins had the same experience in her monumental struggle with the staff of BLOCK at Middlesex Poly. Call the activity by any terminology, Complementary Stidies, Liberal Studies, Contextual Studies, Cultural History it was in reality a part of the Industry of Art education and had to be defended, it was thought, against the Bohos, the Pigment Pushers. "Ten per cent of the week at the minimum and no job losses". Bridget and I preferred not to conduct a separate educational weekly ritual, the Suppository, but go forth into the Studio to find out what the little devils were up to. My first expedition into the studio saw me sit on the very chair a student was drawing."Just seeing what you'd say" was my feeble response to his outrage.

Where a broad understanding and spirit of cooperation was to be expected in the art school, the reverse was encountered in Management Structures, rivalries and divisions from top to toe. Graphic Design and Fine Art. Studio versus Lecture room, Photography versus everybody. Library versus the Stone Pates. My dealings with Fine Art staff were delightful, Nigel Henderson, Derrick Greaves (see other section)at studio lunches when Left Bank terms were rife in the conversation.

But the guttural tendancy in Fine Art was always in danger of breaking the surface. I agreed to a joint talk with the painter Bert Irvin to sixth formers at the Ipswich Museum where the Tolly Cobbold show of contemporary art was held that year. Introductions were made and I launched forth, keenly looking for my opportunity to bring Bert into the proceedings. He seemed to have fallen asleep and after 45 minutes, I roused him with the question about gesture and the surface of the canvas. He pondered for several moments. “Dunno really, I just tosh it on.” I never forgot the feeling of helplessness and the surge of energy needed to right the dinghy.

The minimum expected in education was to help them articulate their intentions and avoid the self-indulgent, even semi-mystical tosh of personal reflection. The maximum was to actually participate in the student’s own projects, guiding research, making introductions and generally encouraging. A sort of discrete Diaghilev.

The provision of Art education always felt too good to be true. The constraints in early days were few, and all manner of curious folk emerged in rock bands, performance rituals and literary poseurs That public money might be being squandered by pranksters contributed to a frantic attempt to make it all look harder. Art Schools became Polytechnics which in turn became Universities. The feigning of Gravitas and Innovation encouraged Modularity, the cultivation of spread sheets, filfaxes and corporate perks. Sensible language describing art and its possibilities degenerated to Marketing Jargon, where the student was the Customer and the Teacher delivered the goods. We were staff at the Supermarket.

All manner of academics from Sociology, Public Policy and dry fields beyond, herded the Visual Folk into a quasi corporation to be scrutinised and tested with a corresponding diminution of the study of art itself. In being an external examiner myself and Visiting Tutor I regularly encountered fugitives from distant disciplines that hadn’t the foggiest notion of the Image and its variations. I was seldom irritated because I had no personal ambition to join the Yahoos in their meetings and alcoholic carousing. The spectacle of those jockeying for power and influence, without qualifications beyond a distant certificate, or a smattering of technical understanding, was frankly hilarious and would have vastly amused the author of The Apes of God. I have explained to all my PhD supervisees that among the many benefits of the award such as impressing friends and family, the Doctorate is like a Golden Shield keeps the buggers off your back, sad and superficial though that may sound. Sometimes the only factor that wins you the argument is when you insist the academic title is added to your name on the document’s circulation list.

Why there has never been a sit com based in an art school ? I shall never know. It has the same potential as Hi-De-Hi with curiously similar underlying structures.

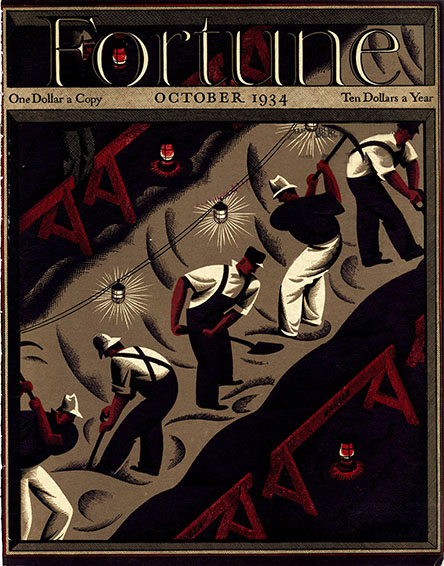

FORTUNE CAME INTO MY LIFE.

Attendance at conferences persuaded me that I had no urge to concentrate my energies on single topics with which I should become associated in the industrial mind. As well as a variant to the naked careerism of presenting research, the published paper was the equivalent of a dog marking its territory.

I did a gig in Oslo at the GRAFIL conference talking about images of the Storyteller for Anna Kristin Hagesaether, our much respected Norwegian MA student. I was on the circuit for conferences organised by American school teachers in Europe, with Cold War imagery in advertising, and Bob Hope as celebrity endorser of consumer projects. As I passed my fortieth birthday I was fortunate to be offered the ideal job at Norwich by Bruce Brown, Head of Design, to work in the studio directly on student projects. “Better having you as a player on the park than shouting from the touchline.”

Regular money was handy as well as the removal of pressures to be responsible for the Art History essay and its grading. It was an observable tenancy that Graphic Design tutors were content to have their students sent out from the studios allowing a longer lunch hour. One illustration tutor told me that she wanted none of her students shown anything that might distract from their own work. My experience was the very reverse, illustrators and some designers were eager to see how other artists responded to the challenge of what Hockney called “ a graphic equivalent”. Damn good to steal from, said Fuseli of Blake. Students were eager, sometimes desperate to see their own visualisations within a political or psychological context, particularly the Editorial Photographers. FORTUNE proved the most valuable of convergence points where the media met.

While still working at Norwich School of Art a wholly new direction came about during a family holiday in Hay-on-Wye. In the late ‘Seventies, the town of Hay-on-Wye had a reputation of being one huge Book Shop; the Cinema, the Fire Station and most available chapels devoted to heaps of books for sale, a few of them actually worth having. Those that remained were sold as slowing burning fuel for central heating. There were summer activities for our kids, Edie and Jack, in streams and pastures nearby. I could easily slope off with a carrier bag at any time of the day and night to start filling the car, a green Mini Estate with a decent sized boot with tailgate.

One shop, we were told, was even open all night. You just left the money in a hole in the wall. Mike Pidgley’s sister had access to an abandoned pub, the Badger, in the centre of the village . There we could camp for the week. Other people, transient guests, would appear, take breakfast, and then never be seen again. One was the actor Tim Spall, presumably observing us as part of his preparations for his next role in a Mike Leigh production.

What sort of book was it that could be bought at two in the morning? With a handful of loose change, when everybody was asleep, I scuttled out to find the dimly lit room in the nocturnal shop near the Fire Station. I was disappointed that there was no assistant in place. And no other customer.

The books were of course inferior to those in the very worst Charity shop, torn, stained, incomplete and unreadable. However the first thing I noticed at the threshold was the smell - a sharp, brittle and high gloss smell. This was not the usual whiff of extreme foxing, dampness or rodent droppings.

In the corner, underneath the wall safe, were three neatly stacked piles of FORTUNE magazines at 20 pence each, mint issues from the early fifties. I found about a dozen issues with photographers I had heard of, mainly features by Walker Evans and Arnold Newman. With this yoke of purchases, I staggered back to the Badger and began to sift through what I had bought. Almost immediately, I developed a hunger for more that night. The nocturnal protocol allowed me regular clandestine visits during the night until the rest of the shop opened at nine.

The determining factor now was how many I could fit in the Mini Estate. The earlier magazines (from the war period) had a mark-up to 30 pence because of the whizz bang factor of armaments and men on the march. The rest of the holiday was a Paradise of gentle ambling through the rolling countryside, with June’s FORTUNE in the evening. I often wonder, by the way, the extent to which I have actually ever ‘read’ the magazine. Just as I got going on some rascal of capitalism, or corporate wheeze, some new scintillating visual feature could be sensed around the corner and my concentration lapsed as I sped through pages in anticipation of excellence.

After a week we were perfectly loaded for the journey back to Norwich, with the purchase of most loose copies from the Night Room piled in the back. I drove with immense tact and care with leaden steering and a song in my heart. Only once did we risk disaster. Stopping suddenly for the traffic lights at a roundabout in Slough, the massive superstructure of magazines lurched forward trapping Edie and Jack in the jaws of the hinged seat. To this day she remembers the smell and the darkness that engulfed her. I remember too the sharp look in Oriole’s eyes as I restacked my purchases in the next lay-by.

The hunger had however not gone away. Once back in Harvey Lane with its huge garage, I could unload, store and sort. Ringing up Richard Booth (Booksellers), I was desperate to track down any copies that hadn’t been rootled out for me.

“No, I think you got them all. But there are two containers coming in from the States next week.” Developing a fiction that I was the reluctant mouthpiece of a large consortium of scholars and librarians (called the CABAL), I bought both containers unseen. I negotiated prices, explaining that the Cabal had unlimited storage but limited budgets. The Booth lorries delivered, and I sensed a profound relief at Head Office they had not been stuck with so many issues, bound and unbound, duplicates and inserts for the Night Shelter. Many were Library discards. Some were mint and unopened. A few disintegrated the moment I looked at them, their amber glue in flakes at my feet.

From the Garage, and reaching to the limits of the garden, came this intense brittle, glossy smell. Later I made finer sensory judgments on the paper characteristics of FORTUNE’s various decades, the antique laid paper of the thirties emitting a bouquet of beautifully ironed elderly linen, the musty twang of the war quality paper stock arousing an earnestness of purpose, the coated paper of the fifties that acted like a nasal de-congestent.

I never really put much store in checking complete runs. I seemed to have most of them, and there was a set for Phil Beard who joined me in the enterprise, and a set for breaking that would be the basis of studying and slide making. No gutters appeared in my teaching imagery, just the majesty of the pages, single and double.

Working as a visiting lecturer at the Norwich Art School I simply didn’t have the clout to develop an exhibition of the material under a wide institutional umbrella. I can’t remember many members of staff at Norwich showing the slightest interest in FORTUNE. One ad-hoc exhibition I mounted in the foyer was removed because a Head of Department wanted to be able to complain the Gallery never showed material relevant to students of Graphic Design. His burly honcho advised me mafia-style that it would not be in my interests to leave the exhibition up despite the student enthusiasm.

Cashing in some shares my father had given me, and with the support of Professor Roy Church, head of the School of Economics at the University of East Anglia, I proposed an exhibition in the University Library, agreed by the dour and suspicious Willi Guttsman, its worthy Chief Librarian. It was to be a tear sheet show but was expensive in glass and fixing. There had to be a catalogue. Penny Hudd, with the help of Sharon Hayles, generously shaped these aspects of the show.

We could now directly approach the contributors to the magazine. Letters received quick replies and the names of Phil Beard and Chris Mullen, that exotic and unfathomable twin Limey research machine, were passed from designer to photographer, to illustrator and to the makers of maps. The delightful Jane Mull whose name and face graced so many FORTUNE Round Tables came over the visit us in Norwich. To my embarrassment she took Oriole and I out for a meal that must have cost as much as the flight over.

The show was much admired by those who stumbled over it and later, in Rochester, generated the interest it should have. Willi did everything he could to suppress knowledge of its existence at the University, even refusing to sell the catalogue on site. Paul Hogarth agreed to come to our private view, but we had decided to feature his reportage work on its own screens anyway. He was contented, giving only a secret smile when hearing about Jane Mull, his research assistant on several trips into the American interior.

To balance any monotony of scale in our world of FORTUNE, Penny Hudd had the Garretto unloading cover made into a ten foot banner, and splendid it was. Phil and I were thinking of making special pyjamas with some of the young Petruccelli’s textile designs in which to attend the Private View.

In its American incarnation in Rochester, the FORTUNE exhibition made a much greater impact. I delivered the contents in one carrier bag to the office of R. Roger Remington at the Institute of Technology. Roger had Frodo-like handed back the keys of power in the department to develop the digital archives at RIT. The display I left to him and his staff. What a trouper he was, and so professional. Oh the joy of seeing the beauty of the display and hearing about its reception by the visitors.

At the time of the show Roger arranged a discussion panel featuring Tony Petruccelli, Walter Allner and Hans Barschel. I still have the tape.. Allner was eager to add to his international reputation, Barschel was wise, but Tony fizzed and laughed with no thought for the future. I told him I would commemorate the work we had done together in some AV mode. Trust me, I said. I do, he replied.

The story of the Summer party of the old hands at the Burcks house in Upper State New York is told elsewhere on my site as is the developmental work for the FORTUNE show Phil and I carried through with Tony. You’ll also find my own account of staying with Tony and Toby in Mount Tabor and documenting his life’s work.

The internet has provided me with the opportunity to extend my compilation in a convenient and flexible way, integrating it with other contemporary magazines, and developments in other visual languages, and to do so in ways no conventional publisher would tolerate.

No doubt one day, a study will be written that does justice to the achievements of this magazine, of this group of people, but until then you will get many happy hours wandering the labyrinthine structures contained within this menu. When that study appears Phil and I will feel insanely jealousy but will also experience a great satisfaction, and expect to be cited, even adored for our original brave and loving efforts.

ART SCHOOL DAYS - BRIGHTON MASTERS AND THE SEQUENTIAL

see also separate section

The Masters Course in Narrative Illustration and Editorial Design (the Sequential) was validated for launch in 1989, in a climate where the very word “Narrative” caused many pure souls to hold their noses. Now, everybody and every event has its Narrative, indeed its story, but then it seemed to corrupt the very idea of Art. “Tell me a story” was tantamount to a surrender to mere illustration and evoked Listen with Mother or Max Bygraves.

In advance of advertising the job running the Course I was invited up to Brighton to be scrutinised. Bruce Brown and George Hardie had known of me at Norwich, and John Vernon Lord's daughter had been a student in Illustration at Brighton. I was invited to lecture on maps and chose to talk about the tyranny of the Ordinance Suvey Map, or the Subjective Diagramatic account of the Landscape. I passed the initial test of not getting pissed at lunch at Marco’s, the departmental Watering Hole near the Pavilion.

Working at Norwich was becoming intolerable. The merger with Great Yarmough School of Art entailed shuffling staff, some with giant bungs to depart. Then came the insidious practice of applying for your own job, or, in my case, being urged to apply to be Head of Complementary Studies, probably to settle a private score of the person suggesting it from behind his hand. The management structure at Norwich gave me little confidence so I was receptive to the idea of moving to Brighton. If you consult the admirable Marjorie Allthorpe-Guyton’s history of the school, the equally admirable A.J.Stephens then Deputy Principal wrote a chapter bringing the chronicle up to date entitled “Bill English and an end to dirigisme…: Imagine this through the voice box of John Le Mesurer, A.J.’s doppelganger.

Much of the creative chaos at Norwich has been written about elsewhere.

Every now and then a memory is triggered. Photocopying documents at the University of East Anglia I got talking to an admin assistant whose husband worked in the CID then investigating financial infelicities at the Art School. She was incredulous at the laxity of procedures and the small mindedness of senior members of staff contacted

A job at Brighton offered a broadening of horizons, a more exciting urban centre and a chance to create rather than respond. For fiteen years contact with the vibrant visual culture of the University pf Brighton, the town’s media communities and the wealth of professional talent requiring a Master’s Course.

My old pal Aaron Scharf (see also section on the Open University) came to give an inaugural lecture, leaving us with the keynote conclusion that it is virtually impossible to imagine anything that was not sequential. This was the licence to take the course everywhere and prove that art was a broad, if unruly, church. The course accommodated paintings of Moby Dick that obliterated each other on a weekly basis, a fold out map of world cinema, evocations of inter-war Berlin, as well as the usual Little Red Wotnot and Gulliver. Only one subject I refused, a tale of a Junior Witch. Not a day passes that I don’t wonder if I curtailed any chance of Marjorie making her fortune.

Thereafter my interests in art followed the individual MA projects and the need to lecture on the appropriate. Switching in 1995 to Practice based PhDs, the need to advise, or at least bullshit intensified.

This approach was the most watertight of excuses to buy more books, and even more books both for tutorials and lectures. It was also an incentive to try and achieve a broader cultural understanding. My Kuwaiti student’s project necessitated an understanding of calligraphic Arabic scripts. Taiwanese students images of the family sent me in one direction. Occasionally the earliest research interests in Brighton would be taken further right up to a PhD award, such as Dr.Jackie Batey’s iron box of advertising simulations, half a marketing analysis and half a Duchampian exercise in an alternative reality(see beneath).

Dr Adele Carroll first approached me at the BA level about her dubious attitude to Graphic Design, only to find I shared her every suspicion. Her PhD was a documentary film supported by intensive researches into the Women’s League of Health and Beauty.

In between Graphic Design BA Course Leaders I was instructed to keep on eye on the second year project work, and spent at least term teaching sound design and the new possibilities of the internet. New technologies promised everything I felt I needed, the storage for retrieval of huge banks of visual data. John Vernon Lord and I faced this shining future created by curiosity and greed, only to find a floppy disc could carry eight images.

I started this section with a description of how I interpreted the concept ART, “The basic appeal was that images presented propositions without spoken or written language.” The Masters Course encouraged me to probe this in a variety of contexts but with due attention to the presence of the written word. Narrative propositions were in contemplation and execution fascinating. It was regarded as a heresy by all Fine Artists teaching at an Art School that you could actually teach artists to do what they wanted to do better.

Working on FORTUNE magazine had sharpened my scrutiny of how photography is used to communicate. Working with Nigel Henderson alerted me to the possibilities of Documentary Photography and the narrative riches of collage. With Karen Norquay and Iain Roy I wrote the Editorial Photography Undergraduate course dedicated to the proposition that it was not sufficient to look mysterious when asked about intent, nor rely on the image alone in its lofty majesty. Writing the documentation for the course documents I found I most enjoyed inventing student profiles of individual need and satisfaction. In launching projects came my opportunity to supply wide contextual information. One project invited a portfolio of photographs on the subject of Kiss.

In Cinema Paradiso mode I supplied a compilation of twenty minutes of what one student called, “a ritual exchange of body fluids.” From Hitchcock to Munch and back again. The first year of students proved we could attract the most interesting and accomplished candidates, Gordon Macdonald, later editor of Photowork magazine, Eric Lesdema and Stephanie Bolt, Maria Short and Danny Green. Clare Strand went off to the Royal College made contact when she returned to Brighton when I worked regularly with her on her projects that took her work to so many international Galleries.

ART SCHOOL DAYS - THE BRIGHTON STUDIO BASED PHD

In many ways the study and the practice of the Sequential decided what art and design I should myself cultivate. There were obvious Pioneers such as Winsor McCay whose artwork I had seen in then Fairleigh Dickinson Library. Using FORTUNE as a base camp I explored American Narrative Painting in Philip Guston and Martin Lewis. The budget allowed us to run a healthy programme of external speakers, Posie Simmonds, etc

The then Head of the Design dep[artment Jude Freeman accepted a PhD candidate in Nabeel Ali, a Kuwaiti student working on a Saudi grant. Being the only member of staff with a Doctorate I was chosen as a first supervisor. Other candidates were accepted on an intermittent, largely unplanned basis but I could slide out of the Masters to concentrate on their studies,

THE PRACTICE BASED PHD

Dr Jackie Batey's PhD project on line

There are arguments as to why the making of images, objects and sequences, might be generally informed by understanding the theoretical constructs that underlie visualisation. The societal context is of considerable importance. It may be a fair expectation that the candidate be aware of the philosophical arguments of the day. The highest academic award cannot be the convergence of intuition, whimsicalities or serendipity. Yes, yes, we know all that.

But what about that visual creator who perhaps started at school, perhaps went to evening classes, attended a Foundation Course, successfully performed the undergraduate entrechat and applied to enter an Masters’ Course. As the portfolio built, as the displays were designed and effected for assessment, as the mature artist’s retrospective revealed a sizeable and significant body of work, exactly why was it that this entire infrastructure, then superstructure be offset even superseded by that thick A4 thesis with footnotes, reference lists, the residue of many interviews, selected periodicals, learned conference papers, and the mighty warp and weft of the conventional thesis.

The original title of your doctoral research would have to be comprehensive as to what you wanted to achieve, and the steps getting there accurately plotted. The pursuit of the distilled phenomena of haemoglobins in a gravity free environment , and the speculation of the role the Merchant Classes played in the English Civil War, suggest a range of reasonable trajectories that bear little resemblance to the body of work generated over three years exploring the role that Emblems might play in the conjuring of Children’s memories of Landscape.

The Studio based PhD, the Practice based PhD, the Phd by Studio practice – call it what you will - converges in a body of work where the critical reflection of the procedures and motives of making are subsidiary to the visual propositions themselves. That the most elaborate, nunaced, explicit or transcendental propositions can be made with pictures alone was the driving force, the consistent armature that held by teaching, my own making of images together, and what I wanted for artists.

In 1995, it seemed easy to start. The only apparent insuperable was the bringing in of External examiners with experience in the Studio based PhD. Practitioners with the confidence to include theoretical and historical constructs were thin on the ground. There were the Bohos (“I just tosh it on”) or the Dry Ones ( “you can read my articles but I am rarely in the studio these days..…”) I shall add more detail in a separate section.

The demand in 1995 was obvious and compelling. Certain art schools teetered into shallow waters. Most of the larger and more prestigious courses insisted on awards only for those candidates who had achieved both a body of work, and a convenetional thesis, in fact demanding a PhD squared. Doctor, Doctor, so to speak. I was contacted by institutions all oiver the world asking for details of what we were doing. Through word of mouth students from Taiwan began to apply because their academic carrers did not progress beyond a certain point at home unless they had a doctorate. If you were an artist, you couldn’t get a Doctorate in your own discipline.

SHORT CONCLUSION-

The award of a Doctorate allowed me to narrow my eyes and breathe deeply at meetings, locked in a sphinx like silence that could be construed as contempt or superiority. Dealing with what research was, what a doctorate should be, seemed to have passed me by. The fees generated from overseas students no doubt did much to assuage any anxiety among the managers.