Florence and Adelaide

Claxton arrear regularly as contributors to the illustrated magazines

of the period. There appears to have been a good representation of

women illustrators such as M.Ellen Edwards who only occasionally gave

a feminine perspective within the magazines on Society, on Love, Ambition

and Reverie. Comparatively little is known of Florence Claxton but she

gained celebrity with the exhibition of her watercolour The

Choice of Paris in the Portal Gallery in 1860, subsequently

published to a mass audience with an almost unprecedented two page colour

spread in the Illustrated

London News of June 1860, the

text accompanying the image showing every evidence of informed hints

from the artist herself (see beneath). The original watercolour is in

the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. It is known

that her father, Marshall Claxton was an artist who, after a period of

study in Rome found a voice in the 1840's as one of the sorry band of

monumental painters encouraged in the Palace of Westminster competitions.

In 1851 he had qualified professional success in Australia and on the

journey back worked in India and Egypt for three years. It is possible

then that his daughters were much travelled and aware of the art world

and its ways. By the late 1850's Florence was beginning to exhibit work

and have several of her illustrations published, particularly in

London Opinion.

TOP ROW - LEFT; "The

Choice of Paris: An Idyll by Miss Florence Claxton." Illustrated

London News 36

(2 Jun. 1860), 541-542.The text that accompanies the image runs,

"The

Pre-Raphaelites were smartly satyrised by Miss Florence Claxton in an

elaborate sketch, exhibited at the Portland Gallery, which, as and artistic

curiosity, we engrave on another page. The picture, as it will be seen,

is divided into two parts–one interior, the other exterior–by a brick

wall. In the interior, the left-hand compartment, the principal group

is that of Mr. Millais presenting the apple to a Pre-Raphaelite belle

ideal,

whom he prefers to a figure of Raphael’s (from the well-known picture

of "The

Marriage of the Virgin"),

and to a pretty, modern, English girl, dressed in the mode of

the day, with plaited hair and crinoline complete. He carries in his

hand a volume of Mr. Ruskin’s, and on the ground is a treatise "On

Beauty," by the same author. On the floor, also, are some of the

famous apple-blossoms which Mr. Ruskin invoked the artists of England

to paint, and the onions, as painted by Hunt, which that gentleman was

so enthusiastic about last year. Behind these we see another Pre-Raphaelite

worthy examining the feet of a female through a magnifying-glass, the

textural surface of which he is copying minutely in his sketch-book.

In the. background at this side is an artist of the middle ages thrusting

one of Raphael’s apostles out of the door; and on the opposite side are

the portraits of Raphael, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and Van Dyck, with their

faces turned to the wall, whilst those of Millais, Ruskin, and–Barnum

are exhibited underneath them to the homage of the public, whilst a mediæval

figure, reclining on a sofa, proclaims their ascendancy through a trumpet.

In the looking-glass over the mantelpiece is seen reflected the window

on the opposite side of the room, and through that window is discovered

the vision of a lady and gentleman walking up a gravel-path to church.

The countenance of the dandy sipping his tea at the left of the fireplace

is intended to express the bitterest feelings of horror and jealousy

at this to him unwelcome apparition. It will be recollected that in a

picture recently produced by Mr. Calderon a lovelorn lady is represented

as about to faint against the garden wall, having just caught a glimpse

of her lover presenting a flower to a girl on the other side of the wall.

In Miss Claxton’s "Idyll," the hapless fair one sees through

the brick wall, for the flower is being presented to her rival (who munches

an apple) inside the room, whilst she is standing outside in a Pre-Raphaelite

attitude of intense affliction. A little beyond this figure is seen an

artist making a careful study of a brick by the aid of an opera-glass.

Looking upwards, we discern a young lady who is being dragged in at the

window by the hair of her head, having lent too favourable an ear to

the serenading monk beneath. Her fiery red hair has partly given way

under the severity of the tension to which it is subject. Behind this

figure is the famous Sir Ysumbras [sic] of 1857, and in the foreground

a pic-nic, where Mr. Hunt’s "Scapegoat" is anxiously waiting

for some of the milk which a female (somewhat after one of the figures

in Mr. Millais’s "Spring") is drinking. The grave-digging nun,

and the sprawling figure of the girl sucking a straw, in the foreground

on the right, will at once be recognised as of the same paternity. This

crowded little composition will afford much amusement to the artistic

world and those who are up in professional incidents and tradition. There

are some follies which are better met by ridicule than argument, and

Pre-Raphaelitism is of them."

The composition is a witty fusion of visual features

from the main works of the Pre-Raphaelite artists, a sort of well constructed

tableau with accessories. The award of the prize by Millais to an attenuated

medieval figure instead of a more conventional ideal of beauty is consistent

with PUNCH's satirical attacks on the movement, typical of the conservative

belief in a Raphaelesque physical type. The tone of the Claxton watercolour

differs from PUNCH in that there is a certain fondness for the motifs,

and even an admiration for the technical complexities in the detail.

Claxton weaves an acid purple hue through the tableaux that is very characteristic

of the movement. I can't think of another such sucess de scandale in

the period that uses this satirical model, knowing winks to a shared

knowledge, fusing the whole into a persuasive whole. It is a catalogue

of information that reads extraordinarily well. Her Idyll precedes

George Du Maurier's satirical exercises A

Legend of Camelot (1866) which gets much nastier with its

references to siupposed preciosity and homosexulaity in the Brotherhood.

The three examples of her work from London

Society are

highly traditional in composition and narrative. Her drapery style, of

line and decoration is a high standard of drawing. The narrative impulse

in her is best expressed by the comparative pairing of men's and women's

dreams, a combination of the erotic and the violent. Her suitors heads

are mounted on the wall as trophies, his comes off to a cannonball.

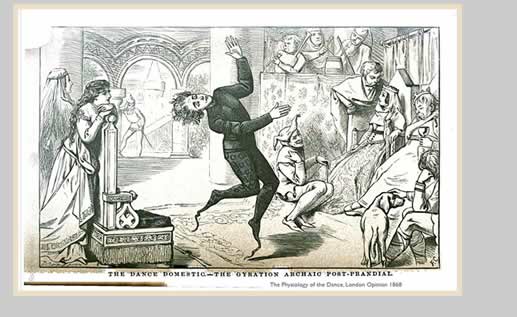

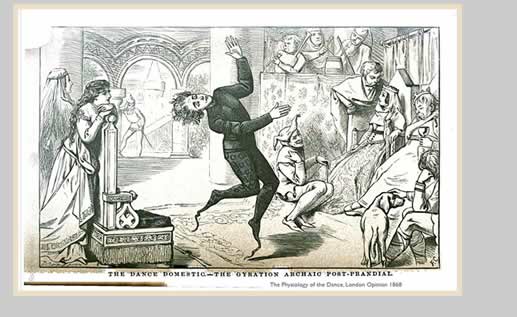

The later drawing is one of a series of satires on Dances through the

Ages (1868) |