BACK

DR FRANK JACKSON, 59A, PRINCES ROAD, BRIGHTON, EAST SUSSEX BN2 3RH

TEL. mobile 07982 032974 text and images throughout copyright

|

INTERVAL BEFORE THE STORM

Dramatis personae The Brotherhood of the Hand, a small society, dedicated to mystery, consists of four elderly men, in equally elderly grey suits, who correspond to the fingers of the human hand. Simon and Annie, brother and sister, have become members of the Brotherhood, as have their friends, Indira, Pei-Ying and Mariko. There is also Adrian the seagull and Sniffer the dog, the eyes and nose of the Brotherhood, Sister Teresa a dedicated nun with strange powers, and Pat, an Irish academic. A new member is Morag, half-policewoman, half-faery. Together, they fight a war against their arch-enemy, Doctor Wrist, and his associates. During a journey to Hyperborea, the land of the faeries, they have succeeded in destroying one of the hated and murderous Wrist family. But now the storms clouds gather. The scene is the seaside city of Brighton.

************

‘We are at war’. There was a silence around the table. ‘You can’t deny it. I know the faeries are fighting a war. They will not admit it, but they are. So are we’. ‘How do you know?’ ‘Instinct, perhaps intuition, whatever you call it. But it is real. Make your own judgement’. ‘If our allies are fighting this war, then they can call upon us to help. They have every right to. If we choose, then what help would we be? Our little group? Would we make any difference?’ ‘It might make all the difference in the world’. Annie stared down at the table, her finger absently tracing the knots and whirls of its wooden surface. In her mind she could see armies marching around the thin contours of the grain, moving inexorably towards the thin straight line of the gap in the table, its edge slightly raised. The faeries’ western wall, defended against an unknown enemy. ‘Annie!’ ‘What! Oh, sorry. I was far away’. ‘Yeah, lost in dreams of your distant paramour!’ Adrian sniggered, grinding his beak together with a rather repulsive rasp. He grinned at Annie, together with a sly look. ‘Oh, shut up, Adrian!’ Annie snapped irritably. ‘Please! Let us bring some levity to this discussion!’ ordered Index Finger loudly. He stared coldly at Adrian the seagull, who rasped his beak again with a rude noise. ‘Let me summarise what Annie, Simon and Morag have told us. Firstly, a murder was committed, and the victim was the faery Hylas. The murder was solved, and the perpetrator’, nodding at Morag, ‘a mechanical cockatrice, was destroyed. Secondly, however, a much more serious development followed. The murder was executed by a member of the Wrist family, who we know wish to found their own dynasty, and become magi, or ruling magicians. To what end we still do not know. But thirdly, this member of the Wrist family, known as the grandfather, was killed by Simon in self-defence in the House of Poseidon, in the faery land of Hyperborea. In so doing, Simon himself very nearly died. We are all very happy that you did not, Simon’. He said this with utter sincerity, and even a note of affection. The others all nodded, smiling at Simon, their faces still pale with shock as Simon had recounted what had happened. Annie looked around. They were all there. The Four Fingers of the Hand, clothed as always in their grey suits, shabby and elderly, as they were. Their three friends, Indira, Pei-Ying, and Mariko, were looking anxious. Pat, the Irish scholar and wit, in his elegant cream suit and garish tie, lounged on the bench, next to the monolithic presence of Sister Teresa, secretly known as the Flying Nun, sitting like a great grey statue in her robes, her half-smiling brown face framed by her wimple. Adrian perched on the end of the great table, his webbed feet pattering, irritably. Unseen, beneath their feet, lay Sniffer, the unbelievably filthy dog, in a shifting pile of matted fur. Annie knew that Sniffer’s black, beady eyes, despite his apparent laziness, and ignorance of personal hygiene, missed nothing. Finally there was Morag, the half-faery policewoman, who had been with them in Hyperborea, sitting grim-faced on her right. Her brother Simon, was on her left, facing the Four Fingers. Annie shivered. She had seen them all do the same, as Simon told his story. The angel of death had brushed their faces lightly with his wings, as they realised how one of their own had been so nearly lost. No longer a game, Annie reflected, as she had thought at the very beginning. Now it’s a matter of living or dying. She suddenly felt that awful jolt of fear that comes with realisation of potential loss, of what might happen, in the worst sense. She tried to scramble her thoughts back and concentrate on what was being said. ‘There are two situations which are now apparent’. Index Finger announced. ‘One is immediate. The Wrist family have lost another member of their family’. ‘Remember they’ve lost a daughter, Venoma, who my sister killed, in mortal combat. In self-defence. They also lost a nephew, Leonard, who blew himself up, trying to do the same thing to us’. ‘True, but it is quite possible, that they will strike at us again, in revenge. How, when, or where, we do not know. If our allies are otherwise pre-occupied, then we can only stand and defend ourselves, for the time being at least. I think they will bide their time, until they are ready’. said Little Finger, abruptly. ‘Revenge is always sweeter, when it is planned’. sighed Sister Teresa. ‘Excuse me’. asked Indira, plaintively, ‘Does that mean that we’re all at risk?’ ‘Yes’. said Index Finger, simply. ‘Fine. Just thought I’d ask’. ‘The second situation is this’. Third Finger interrupted. ‘if the faeries are truly at war, and the dragons are engaged elsewhere, then we are on our own. But we must be concerned with what is happening in Hyperborea. The faeries are our allies. Their situation is our situation. We must do all we can to support them. But what do we know about their possible war?’ Morag held up a finger. ‘This is all circumstantial evidence, not proof. We can only say what we’ve seen. But I believe Annie, and from what we have heard from our paramours, as some daft bird puts it’, she glared at Adrian, ‘ the faeries are secretly at war, like it or not. But what can we do, if they won’t acknowledge it?’ ‘Because they’re too proud!’ Adrian scoffed, making that irritating rasping sound with his beak again. ‘Them lot won’t admit to anything! Not even your precious boyfriends!’ Both Annie and Morag froze, their lips drawn back in fury. Everyone else sat back, waiting. Annie’s surge of fury passed. She relaxed, looking a picture of innocence. ‘What’s the matter, Adrian? Have you had a bust-up with Gerry, Your paramour? I’m not surprised. How she puts up with your bad temper, I don’t know. Sort your own problems out’. Morag leant forward, smiling maliciously. ‘What’s her proper name, Adrian? Is it Geraldine? What a nice name’. ‘Mind your own business!’ ‘She does have a point. Why should she put up with your arrogance and conceit, not to mention downright stroppiness? Put your own house in order, Adrian, before taking it out on anyone else’. Annie smiled sweetly at the infuriated seagull. ‘Order, please!’ interrupted Index Finger. ‘We cannot afford to quarrel between ourselves. There is too much at stake’. ‘Go in peace, Adrian. You must make amends to your true love’. Sister Teresa said this seriously, but with the hint of a grin across her broad face. ‘ Right! I’m off!’ Adrian flapped towards the open window. He perched there for a moment, in profile, lifting his beak disdainfully. ‘Pheasants!’ he muttered, and soared away. Everyone giggled, then Index Finger raised his hand. ‘This meeting is closed, until the next time’. ‘Wait a moment! Simon said, slightly confused. ‘What do we do now?’ ‘Nothing. We wait. The storm is gathering’. replied Index Finger, quietly. Simon sighed and got up, but as he did so, he felt Sister Teresa’s heavy hand on his shoulder. He turned, and looked at the broad smile on her broad, moon-like face. Pat grinned at him beneath his luxuriant white moustache. ‘Pat and I would like to say how happy we were that you survived that murderer’s attack. We may not have said so, but everyone here is relieved and delighted that you have returned to us’. ‘Amen to that’. Pat echoed. Simon felt embarrassed and awkward. He looked around at his sister and Morag, engaged in animated conversation with Indira, Pei-Ying and Mariko. His face softened. ‘I’m glad to see Annie and Morag so happy’. He struggled to find the right words. ‘I mean, I think they seem to be more at peace with themselves’. Sister Teresa looked across. ‘Yes, they are. They have discovered love and affection. Better than sadness and mourning. The same for you. This Ragimund, you care for her very much, don’t you?’ ‘She means a very great deal to me’. replied Simon softly. ‘She can be a ruthless warrior, but she can also be the loveliest companion that I could ever want’. ‘Like a lamb that can turn into a lion, eh? A bit like you and your sister, perhaps?’ Simon looked hard at Pat. But there was no malice, there, only a touch of sadness, or nostalgia. Not for the first time, he wondered about the relationship between Sister Teresa and this gentle Irish scholar. What had happened in years past? He smiled. ‘What do you think will happen now?’ he asked. Sister Teresa shrugged, her robes ruffling around her large bulk. ‘Nothing’. she sighed. ‘For once, we have a space to breathe and enjoy. Soon, the season of war will come, after winter. But’, she smiled back at him mischievously, ‘Let us enjoy it while we can, and take stock of ourselves. Think, instead, of your friends, and lovers’, she added with a broad wink. That is what they did. *************

Days followed days, month after month falling into each other, as each segment of time fell into its allotted space. Christmas and the new year followed as parts in an exorable puzzle, warmed and enjoyed, then put away again as favourite toys in a cupboard until the next year. The kindness of the seasons fell upon them, as inevitable as a warm, comforting cloak. Snow fell in January. Small darting figures, black against the snow, shrieked and yelled as they pulled sledges, leaving soft grey-blue tracks behind. The skeletal forms of trees, against the dark leaden sky. stood like dark cracks in the wintry vision. A dark blue band of sea hovered in the distance between land and sky, poised above the scattered landscape of red and ochre of the city below. The passing of the seasons continued. The white blanket of snow disappeared, to be followed by the cold shreds of rain, laying bare the pallid surface of the soil and grass beneath. Then came the sunshine, its shallow warmth slowly and gradually changing the landscape into varied hues of soft, buttery green and creamy-yellow. Dark green shoots began to pierce the surface of the land, in open spaces and between the pavement slabs, echoing the quiet green leaves that began to unfold and curl, clothing trees once more in the breath of spring. Annie looked out on the garden, seeming to yawn and stretch in pale leaves and dark twigs, after its long sleep. The full light of the sun fell upon her face. She felt happy and content, free from the constant anxiety and worry that had troubled her for the last two years. At last she could enjoy the sheer pleasure of their garden, opening out and finding warmth in its new-found spring. The little brick path that she and Simon had laid, led to the dark end of the garden, that she loved, a small grove, camouflaged and hidden from sight, where they had built a small cairn of flint-stones, dedicated to no-one in particular, but just for enjoyment and simple contemplation. Our little shrine, she decided. Not for anyone , but everyone. Their winter had been punctuated by small gifts and letters from Hyperborea, the land of the faeries. Sometimes they had been just tiny translucent pebbles, still warm from the palms that had clasped them: memories and mementoes of their journey to Hyperborea. At other times, they had been a small page, written on little rolled up parchments. She kept them in a small inlaid box under her bed. Letters of affection from Helios, who declared how much he felt for her. She remembered how he had squeezed her hand tightly, when they departed, asking her when she would come back. Simon and Morag had also received similar messages, which they all kept secret. She also knew, and treasured, how Morag looked, at their New Year’s party – deliciously pretty and radiant, and for once, genuinely – happy, and at rest. Then, too, their birthdays had arrived, with something of a shock. Both she and Simon had suddenly realised that they were now sixteen, a concept of age that Annie was still trying to come to terms with. She had giggled and laughed with the others, like a little girl again, during their joint party, but when the strange parcels dropped with two successive thumps on the garden lawn during the night, they came as an awakening. Both she and Simon had opened them together, to reveal two long faery swords, their hilts bound in black leather, woven in strange curling patterns. With them were two shorter swords, designed for close combat, and not as curved as the larger. She also remembered how their mother had stared at them, her eyes welling with tears, then turned and rushed from the room. Annie had recognised her sword. It was the one she had broken when killing Venoma, now repaired, and still as hard and deadly as ever. Poor Venoma…. ‘Annie!’ She looked down, startled. Simon was standing below her, in the garden, clutching school forms in his hand. He waved and then came in and ran up the stairs into her room. Annie turned away from the window, with a sigh. He sat down beside her on the bed. ‘Where were you, Annie?’ he asked gently. ‘I don’t know. Back in Hyperborea, I suppose’. She grinned at him. ‘You’ve come to remind me of tedious and boring things, haven’t you?’ ‘Exactly. Such mundane and trivial details like GCSEs and our history project, that we have to decide on by the day after tomorrow’. ‘Damn! I’d forgotten all about that!’ She muttered some further, rather choicer words under her breath. ‘I’ll pretend I didn’t hear that. But seriously, Annie what are you planning to do for your project?’ Annie shrugged helplessly. ‘I’m not sure yet. What are you going to do?’ she asked challengingly, folding her arms. ‘Roman trade and naval strategy’. he said triumphantly. Annie burst out laughing. ‘I knew it! You’ve never been the same since you saw that faery trireme in the harbour at Druard, have you?’ ‘No, I haven’t’, replied Simon, dreamily. He pulled himself back with a jerk. ‘Come on, Annie, what’s your project?’ Annie thought for a while, and then, an idea came. ‘I know’, she announced, ‘Hyperborea – a case study in utopian fiction!’ Simon stared at her for a moment, his forehead furrowed with thought. Then he grinned. ‘I think that’s a brilliant idea! Eyewitness accounts, on the spot recording and analysis! Excellent!’ Annie smiled back at him affectionately, remembering when they were just irritated, constantly at each others’ throats. Now, they had been through so much together, their minds and thoughts seemed to mingle, more in harmony. They no longer quarrelled. She was still afraid for him, knowing the deep emotions he hid underneath the surface. Still, the currents of their ideas and views had become closer, as the bond between them had intensified. Her face fell. ‘But I need more than that. I have to refer to published sources, books, anything, to justify it. Where do I find those?’ ‘I have the answer’. Simon held his index finger in the air, somewhat smugly, Annie thought. ‘Do we not have access to an important archive, bequeathed to us by our late friend, Mr Cuttle?’ ‘Yes’. said Annie, slowly. ‘And does it not reside under the curatorship of our good friend, Chris?’ ‘Yes!’ shouted Annie excitedly. ‘And might it not have all the material we need for our projects?’ Annie sat back, happily. ‘You’re right! Why didn’t I think of that?’ ‘Ah, men are from Mars, women from Venus’. ‘What on earth does that mean?’ ‘I’ve no idea. I’ll ring Chris, and set a date and time, at his convenience, right away’. ‘Oh, and, Simon’, Annie called after him, ‘Ask Chris if Morag can come as well, if she’s free. She’s half-faery, so she can probably help me find what I need’. ‘Of course’, said Simon from the doorway. ‘he’s got a soft spot for her. Who wouldn’t, if a pretty young half-faery policewoman wants to come and see your library?’ He winked. ‘Just remind him that she’s also got a very nice faery boy-friend, too’. She winked back.

*************** ‘Are you going to tell the faeries about what you’re doing?’ Morag asked, as they walked up to the large, cream-painted corner house where Chris lived. ‘No. I’m not sure whether they would approve. They might think that I’m giving away military secrets or something. But I don’t see why. No-ones going to believe it anyway’. ‘Probably not. After all, they don’t know what we know, do they?’ Morag and Annie smiled at each other, as Simon rang the doorbell. ‘What a very pleasant surprise! Do come in! Morag, too! Come and have some coffee, before your labours begin’. They followed Chris into the hall. Morag looked around appreciatively at the drawings, posters and watercolours that covered the walls. I wish I had more space for things like this, she thought, remembering her tiny flat. ‘Right’, suggested Chris, as they sat around the table in the conservatory, overlooking the luxuriant little garden, that Chris’s wife, Oriel, tended so well. ‘I’ve now shelved all the books in the Cuttle Collection, so that should be easier for you. Do you want to go and see what there is? Then while you’re doing that, I’ll take our Morag for a tour of the library, if that’s all right with you, Morag?’ Yes, please’. said Morag, feeling delighted and flattered. So Annie and Simon walked down to the garage, where more of Chris’s book stock was kept, whilst he and Morag disappeared into the front room. Annie and Simon looked around the shelves, neatly stacked with cloth and leather-bound volumes, together with rows of periodicals and magazines. ‘Wow!’ Simon breathed. ‘There’s more here than I thought!’ Annie had pounced gleefully on two or three large leather-bound books, spreading them carefully on the small table in the centre of the garage. ‘Look, Simon! Histories of the faeries! These must be priceless! Here!’ She turned over the cover of the book. ‘A True History of Faery. An Account of Supernatural Things by Algernon Harborne, dated 1853! And this one, Being a True Story of Faery-Land, Its Customs and Origins, 1821, by Frederick Pentwhistle! Civilisation of the People known as Faeries, Roderick Simpson, 1921! Here’s another, Customs and Beliefs in Faery Culture, Maeve Warner, 1933! This is gold-dust, Simon! Bless you, Mr Cuttle!’ Simon looked up complacently from his large pile of books. He picked up the one on the top. ‘The Trireme in Greco- Roman civilsation. Including Detailed Plans and inventories of Roman Sea Power. Hiram Sethwick, 1947. There’s more. I’ve got all I want, Annie!’ They staggered up the path, back into the conservatory, with their piles of books, and dropped them heavily onto the table, gasping. ‘I believe you seem to have got what you want. Is that enough?’ ‘Thank you, Chris. Can we take them away with us?’ ‘Of course! It’s your archive now. Your Mr Cuttle gave it to you for this purpose, didn’t he?’ Annie suddenly looked at Morag. Her delight at seeing Chris’s library seemed to have evaporated. She was staring wistfully and longingly at the pile of books on the table in front of Annie. ‘What is it, Morag?’ she asked gently. Morag began to twist her hands painfully. ‘Annie, would you mind, when you’ve finished with them, I mean’, She was biting her lip, sadly, ‘Could I read them? I..I just want to find out more about who I am, where I come from. Please, I just want to know more about my mum, what she believed in. I don’t know anything really about what my background is, my heritage, or anything. It would help me to find out what I really am. I’ve seen my country, and my mum told me a few stories about it. But that’s not enough. I want to find out more. Please, Annie’. Annie reached across, and squeezed her hand. ‘You don’t have to ask, Morag. We understand’. Morag smiled gratefully at her. Chris broke the silence. ‘Anyone want more coffee?’ ************

For the next month and a half, they pored over the volumes that had once belonged to Mr Cuttle. They drank in the concepts, myths and realities that surrounded the faeries that they had come across. Piece by piece, they began to understand the strange people that they both knew and cared about. Sometimes, it was distressing, and Annie wept tears, occasionally having to wipe them from the page she was reading. Simon stayed in his room. For all she knew, he was experiencing the same emotion. They met at meal-times, neither talking about their reading, and the writing that they put down on paper. They became absorbed, not even communicating with their friends and companions. Morag stayed away, busy with police work. But, at last, it was done. Annie walked along the landing and knocked on Simon’s bedroom door. ‘Are you in, stranger?’ ‘Come in, Annie, I’m finished’. Simon was sitting in front of his computer monitor. ‘I’ve done my project as a multi-media presentation! Look, Annie, and be impressed!’ He fingered the keyboard. There, on the screen, was a great faery trireme, oars lifting and thrusting each side as it carved its way through the sea towards them. On board, Annie could see glinting helmets, as the trireme rowed towards them and then turned majestically, revealing the great painted eye on the prow. It swept past, it’s curved stern carved in the shape of a huge swan. The oars rose and fell, splashing and gleaming in the blue sea. She could hear Simon’s own voice in the background, talking about the fighting power and the great cargoes of precious goods, carried in the smaller and rounder ships in the distance. The two great square sails, each bearing the deep blue sign of the pentangle, billowed and flapped, as the helmsmen skilfully leant on the massive steering oars at the rear, to manoeuvre the ship into port, rounded red and gold shields, mounted in a glistening row on the rails of its upper deck. ‘I’m afraid my project’s not as spectacular as that’, Annie said mournfully. ‘I can’t do that sort of stuff. I need some advice. I’m still not sure whether I’ve done Hyperborea justice’. Simon looked at her. She sat fidgeting and uncertain, even confused. ‘Can I make a suggestion, Annie?’ he suggested, rather awkwardly, ‘Do you mind?’ Annie smiled. ‘I can remember times when you wouldn’t say things like that to me’. ‘That’s in the past. We’ve moved on since then. But why don’t you tell us what you’ve found? I don’t mean you should read it out, but just tell it in your own words? This evening, perhaps?’ ‘I’d really like to do that, because I feel so, sort of, self-conscious about it. But you said “us”. Who do you mean?’ ‘Ask Morag to come. She’d really like to. It’s part of her, isn’t it?’ Annie hesitated, and sighed. ‘All right, perhaps I should. I just wish I didn’t feel so worried about it’. ‘That’s because you and I are so close to the faeries. Don’t be upset, Annie. I know its very important to you. Let us help’. ‘OK. This evening, then’. But she still felt disquieted. ************

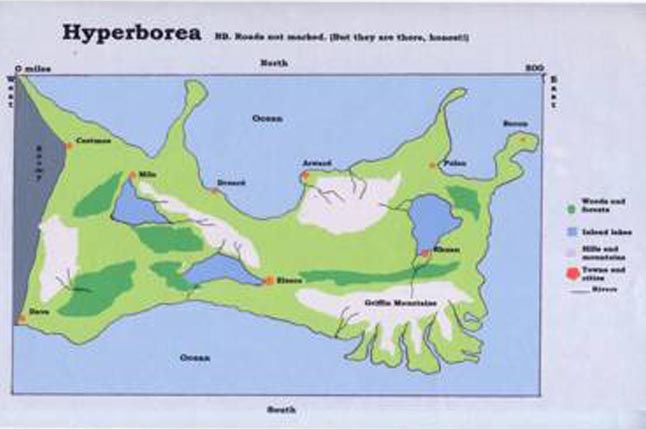

The three of them sat together in Simon’s bedroom. Annie was shifting anxiously through her notes, looking worried and unhappy. Simon was absently ruffling through his fair hair. Morag felt tense and worried. She glanced up at the faery swords, in their scabbards, hanging on the fireplace wall. These children had used these in battle, she thought, long before I knew them. Dear lord, I hope they never have to use them again. Simon looked across at her. She looks so beautiful, he said to himself, appreciating her long slim legs and her profile, the smooth, straight nose, wide soft lips, slightly parted, and her dark eyes, framed by shoulder-length black hair, pushed back behind her elegant ears. (Morag is truly a faery. She so reminds me of my lovely Ragimund, thinking of her with a deep pain). Annie was muttering soundlessly to herself, occasionally brushing back her unruly mop of dark hair. Then, she sat down. Simon pressed a tab on his keyboard, and a coloured map of Hyperborea appeared on the screen. Annie pointed at the map. ‘Look, she said, ‘That’s the land of the faeries, a great peninsula, about the same size as England. There are big mountain ranges, huge and craggy, rising to over twelve thousand feet, and perhaps more. There are three huge inland lakes or seas, whose names I’ve not found out, fed by rivers from the mountains. There are great swathes of forest, deep and dense, as you can see. There are great promontories on the north coast, stretching out to protect the harbours and bays. In the south-west are great fjords, with enormous mountains behind, where the griffins live, though we haven’t seen them yet’. ‘What are griffins?’ asked Morag, bewildered. Simon answered. ‘They’re large flying beasts, with the body and tail of a lion, and the head and shoulders of an eagle. They have strong sharp claws, like a lion. Ragimund told me that the faeries use them as mounts to attack enemies and keep watch. A bit like aerial cavalry’. ‘There are several cities. Elsace, we know, because we’ve been there, with its massive sort of cubic castle. That’s the capital city. But there are others. The great port of Druard, on the northern coast, the main port of Hyperborea. You remember, Morag? Huge, crowded, teeming with all sorts of people and races from many different lands. It was a really wonderful place, so exotic! That’s where we met Helios and Haga’. ‘Of course!’ Morag smiled at the memory. ‘And the horses’. She added. ‘In the north-east, there is Pulan, another port, with the large town of Becon, right on the north-eastern promontory. That’s a military port, where the faeries moor their warships. Their triremes and biremes, Simon, together with other merchant ships. Then, inland, there is Rhuan, between two rivers that flow down from the Griffin Mountains. Helios told me it was one of the most beautiful cities in all of Hyperborea’. Annie said wistfully, and recalled herself. ‘In the west, on the edge of one of the great lakes, is Mila, another large city. Even further west, on the borders of Hyperborea, are Dava, in the south, and Cestmos, in the north. Beyond that, I don’t know’. ‘Annie, if the faeries have such a large port, and have such strong trading relationships, what do they buy and sell?’ asked Morag. Annie was staring absently at the screen. ‘Sorry. It seems that the faeries export cattle, sheep, wool, flax and cotton. They also sell precious metals, which they mine from the mountains. Things like gold, silver, copper and iron, which are in great demand in other lands. But they also make wonderful things in metal, hand-crafted. You know that. We’ve all seen those beautiful things like candle-holders and tripods, bowls and cups. People from other places love them’. ‘I remember! Ragimund showed me this bowl once! It was made of silver, inlaid with gold, in all sorts of abstract patterns! I thought it was one of the loveliest things I’d ever seen!’ Simon exclaimed, excitedly. ‘But what of the faeries, Annie? What about them? What about their culture? Where are they from?’ Morag was leaning forward expectantly, eager to know more about her mother’s people, her people. ‘What did you find out?’ Annie hesitated, for several moments, conscious of Morag’s curiosity. (She has a right to know, she felt. Why, oh why, does Morag seem so desperately curious, about her own background, her heritage? Surely, her mother must have told her? But perhaps she didn’t. Perhaps she kept it from her, wanting her daughter to grow up in a human world. But Morag needs to know. To make sense of who she is, and where she came from). ‘This is where it got difficult’. she began to explain. ‘Why?’ asked Simon. ‘Because all the authors I consulted, didn’t seem to know where the faeries came from. I don’t think any of them had ever been to Hyperborea. We know, but they only seemed to have gone by other accounts from other travellers, and word of mouth. But I will tell you what I think. The faeries came from some Celtic tradition, where they were nomads, and survival was the only thing they cared about. That explains their ancient native language, that even Pat found it hard to decipher. They were wanderers, fighting their way through a world they could barely understand’. ‘Then they were warriors’. Simon murmured. ‘I’ll come to that in a moment. Please, I’m trying to understand this myself. What I don’t know is why they are what they are. I’ve written it up in more detail, but how and when is another matter. Let me give you my hypothesis, what I think happened’. Annie took a deep breath. ‘Let’s suppose that the faeries, in their wanderings, found themselves trespassing into other dimensions. Suppose that they found other cultures and civilisations that they could borrow from, and adopt as their own. Suppose that they found our world. They saw ancient Greek and Roman civilisations, models for what they hoped to find in their own land, if they could. They eventually found a place, a country, that they could call their home, after all their search. They settled there, and retained all that they had learnt, the architecture, the culture, together with others that they had seen – warfare, customs and life. They settled, and made it fertile, but jealously holding onto the way of life that they had established, keeping themselves at a distance from others. They became what you might call a static society, rooted in a homeland that they dearly love and would fiercely protect to the death. That is Hyperborea’. Morag looked down at the floor, her hands were nervously twisting around each other, though she didn’t even notice. She spoke. ‘I believe you, Annie, I really do. It all makes sense. But how and why have they become so involved in our world? Why do they even bother to have any communication with us? Why should my Mum, come here and marry my father, and become a policewoman? What brought her here?’ Anie looked down at her notes again. She desperately wanted to give Morag some reassurance but she wasn’t sure how to. ‘Look, Morag, The authors of the books I’ve looked at, are a bit better on this. They seem to say that the faeries have a close kinship, their words, not mine, with our world. It may be that they know our world better than others. I found a passage where, who?’ She looked down again at her notes. ‘Here, old Pentwhistle said that he thought the wife of a landowner, who he was distantly acquainted with, was a faery! He claimed that the faeries knew our world so well, that they intermarried with earthly women, that they produced children, both faery and human! He thought it was marvellous, that it would improve the human race no end!’ ‘Thanks very much. It’s nice to know I’m of good breeding stock!’ ‘Annie didn’t mean that’. Simon intervened, hastily. ‘You’d better finish. I think I know where this is going’. Annie began, sadly. ‘They ride out into our world, arrogant, and determined to make their presence felt. If you look at all the old mediaeval stories, like Gawain and the Green Knight, Sir Orfeo, and so on, they can be seen partly as a translation of our old myths, but also as descriptions of what actually took place. The faeries rode out in Preston Park, not so long ago, when we first came across them. Their world is shaped by our world, but our world has been shaped by them! We’ve been there! We’ve seen it!’ ‘But there’s more, Annie’, Simon interrupted. ‘Its about them. Tell us why I’m in love with Ragimund, who I still don’t understand, and why both of you have found affection with faeries, whom you never met before until we went to Hyperborea?’ Annie walked across and sat down on Simon’s bed, next to them. ‘Do you remember?’ she asked quietly. ‘When Helios asked me to come to his old home, outside Elsace, where he grew up, and meet his family? He wanted both of you to come too. It was because he wanted to show me what faeries were like. Do you remember?’ Simon and Morag nodded. ‘It was wonderful’. Morag said wistfully. ‘It was one of the first times in my life when I felt I belonged. Apart from the police force that is’ she added hastily. ’But’, she went on gently, ‘the faerys made us so welcome. His mother and father, who looked so like him, his cousins and nephews, his grandmother and father, and the little ones, children, rolling and tumbling around, and pulling my hair. The older ones, though they didn’t look old at all, sat on chairs, and laughed, as we all sat around that bonfire outside, with tables and oatcakes toasted in the flames. Haga sat by me, and held my hand, and told me funny stories, just like here, only better, and naughtier. Whoops! They were good, though!’ she added defensively. ‘I can imagine, especially with his tongue stuck in your ear!’ Simon said, with a mischievous glance at Morag, who blushed suddenly, then smacked him hard across the arm. ‘You should talk! You and Ragimund, well! And as for Annie and Helios….’ Let me get on!’ Annie said hurriedly, standing up suddenly. ‘We all need to understand this’. She looked down at her notes again. ‘We know, by now, and through personal experience, what faeries are like. But, through research and analysis, I also know about the faery culture, and what it means. Faeries are raised from childhood to accept war, and to defend their land, that they have fought so much for. Let’s take it from an early stage. They are monogamous, in that when they commit themselves to a mate, it is for life. This is easier because they do not age. They love each other until death, however that happens. They live for a very long time, and they are so much older than we are, or we can imagine. But they live and love, like we do, and protect their land, that they wanted so much. But there is more. We know now, that they live, because of that, in a very militarised society. Every faery is a soldier as well, man or woman. Every faery child has an education, which is very comprehensive. Languages, science, poetry, but above all, self-sufficiency. As soon as they walk and talk, they learn how to bear arms, every single one. They are brought up on the arts of war. If their parents are called away for service, the older children look after the households and the farms, until they return. Every faery is a potential soldier, from when they are very young. They are taught the use of weapons, and fight whatever threat there might be. From the age of twelve onwards, they are part of a military family, and subject to military service. They are drilled in practice and become skilled with all sorts of weapons – spear, shield, sword, bow, and so on. They know how to ride horses, sail ships, and even ride the griffins, if need be. Their childhood is based upon knowledge and experience. They will be sent out on patrol, they will ride as messengers, they will man oars on your beloved triremes, Simon, as well, as part of their training. They become versatile and strong, and skilled. They are trained to fight. To the death’. ‘Do you remember, Morag?’ Simon interrupted. ‘When we passed their schools, those long low buildings, and the children outside were practising forming battle formations, and swordfights? You were quite horrified!’ ‘I was’. Morag shivered. ‘I thought they should be playing hopscotch or something. Just playing. Just being children. But now Annie’s said this, I find it rather terrifying. What happened to that time we thought of as childhood?’ She looked across at Simon and Annie as she said this, and felt chilled suddenly. Simon caught her eye. ‘Annie and I don’t have a childhood any more. We lost it long ago, when we became involved with the Brotherhood. Its gone. We’ve grown up, long before our time. We’ve had to fight and kill, to survive, and defend ourselves. We’re not children, now, and never will be again’. ‘’Let me finish!’ Annie said sharply. She came and sat down again beside Morag, and looked at her steadily. Morag wasn’t sure what to do. She looked at Annie’s large, gentle brown eyes, thinking how deep and soft they were. Not the eyes of a child, she thought. She began to be aware of what Annie was saying. ‘Morag, you mustn’t judge the faeries. You are half-faery yourself. I haven’t finished what I was going to say’. ‘I think you are, too! I’ve seen you both! Your eyes turned grey! I saw it! Don’t tell me that I imagined it! Wait a minute! All this is a pretence! You’re trying to tell me that I’m not a faery at all! You’re just telling me to go home and not be so silly! All this crap about what faeries are! All a load of shit! Piss off, the pair of you, and good riddance!’ she stood up suddenly, and then Simon’s hand on her shoulder pushed her down again, firmly on the edge of the bed. She looked at Annie’s eyes. They were hard grey. She looked up at Simon, standing beside her. So were his. ‘Your eyes are grey”. she said somewhat stupidly. ‘So are yours’. Annie said, flatly. They sat next to each other, staring at the map of Hyperborea on the screen of Simon’s monitor. ‘What brought that on, Morag?’ asked Simon gently ‘I’m sorry’. said Morag, miserably. ‘I don’t know why I lost my temper. The least of all, why at you? I don’t understand it’. She turned and looked at Simon. ‘Particularly you, Simon. You were almost killed there. Please forgive me’. Simon smiled and leant across and playfully ruffled her hair. ‘Stupid copper’. he said, affectionately. ‘That wasn’t the faeries’ fault. You just didn’t like what you were hearing. But there’s more. Let Annie finish’. Annie stood up again, and gathered her notes. Her eyes were her normal dark brown, Morag noticed. ‘It’s wrong to see all faeries as the same’. she paused. ‘Some of them are different. A lot are dark-haired, like Ragimund’. ‘Helios and Haga as well’. Simon muttered, slyly. Annie ignored him. ‘Some are very blond, and some are red-haired, and even freckled, like Helios’s cousin. Do you remember, Simon?’ Simon nodded. ‘Of course. You sat talking to her for ages, when we met at his parents’ farm. I thought that she even had a tiny little trace of an Irish accent. She reminded Annie of Rosamund’. ‘Rosamund?’ Morag asked, enquiringly. ‘She was human, but became a faery. She was killed in the great battle on the beach, a long time ago’. ‘Oh’. Said Morag, meekly. She decided not to ask any further. It was obviously too painful. Annie put her little sheaf of notes down on the desk, next to the monitor. ‘They are tall, beautiful or handsome, as the case may be, and they can be the gentlest, warmest, kindest and most loving people you could ever meet. Hospitable, caring and sometimes very funny and humorous. Do you remember Helios’s little nieces braiding your hair into little love knots, Morag, when we were all sitting around the bonfire outside? Mine was too short, but they had great fun with yours!’ ‘I know! Giggling all the time, and sniggering at Haga! Cheeky little things! Took me ages to unwind them next day!’ Simon interrupted. ‘They write wonderful poetry as well! They recited them to us. And they make lovely music and sing beautifully. Not campfire stuff, but very melodic and terribly moving. They sang in their own language, a kind of Gaelic, or Celtic, or something, but very expressive. Well, I appreciated it, which is something which doesn’t happen often’. ‘No, it usually takes an earthquake. But the real point I want to make is this, and we had an example of it just a moment ago, between us. Its… I’m not sure how to explain it’. ‘Bad temper? Violence? Raging fury? Sudden change in mood? Volatile?’ ‘That’s it! Volatile! That’s what I want to explain! Just like you were, just now, Morag!’ ‘Thanks. Just blame me, as usual’. ‘No listen!’ Annie dropped on her knees, clasped Morag’s hands and gazed up at her earnestly. ‘You lost your temper just now, and so did we, because something close to you was threatened, as you saw it. That’s why you lashed out. That’s what faeries do! If they feel something very important to them, their security, their loved ones, whatever, they do the same! Think, if you wanted to make a faery really angry, what would you do?’ ‘Threaten their land, their home?’ Simon said, softly. ‘Yes!’ ‘Is that why they are so fierce and protective about their western boundary? Why they’ve built a huge wall there against their enemies’. whispered Morag. ‘What?’ They both stared at her. ‘Well,’ Morag said, uncomfortably. ‘When I was talking to Haga, he said something about it. But when I asked him again, he became evasive, and changed the subject. He just didn’t want to talk about it. I didn’t know why at the time’. ‘The same with Helios’. ‘And Ragimund. I was a bit puzzled about that’. They all looked back at the map of Hyperborea. There was a dark line, that stretched unendingly from north to south, ending at the coastlines. There was only dark grey beyond, with a stark word, “enemy”. ‘So that’s it’, Annie murmured. ‘That’s why they’re preparing for war. There’s a new threat. They’re getting ready to defend their homeland. They wouldn’t tell us, because they don’t want us to be involved. It’s not our fight’. ‘Yes it is!’ They both looked at Morag. ‘Your eyes have turned grey again, Morag’. Simon remarked, quietly. ‘I know! I also know’, Morag continued, her eyes still fixed on the screen, ‘that’s the land where my mum was born, where she grew up, and played as a little girl. Her home, that she loved so much, even though she never really talked about it. Perhaps it’s mine, as well. I know I’ve never felt such happiness in my life, when I was there. if I have to fight for it, I will. I owe it to her, and to myself. If I can, I’ll go back, with or without your help, if necessary, and,,, defend it. I mean it’. Annie sat back on her haunches, her hand on her knees.

‘You really are a faery, aren’t you, Morag?’ she said very carefully and quietly. ‘Yes, and proud of it! Annie leant back and grinned. ‘A faery copper! We’re so proud of you, too, Morag’. Simon stretched and grunted. ‘None of us have ever been the same since we went to Hyperborea. We’ve all changed. Is there something else, Morag? What is it?’ ‘Tell me what my mother said to you in Purgatory! I’ve already said to you that I know you met her there, even though you lied to me. I can forgive that. But do you really think I can be at peace unless I know what it was she said about me? What was she doing there? Was she sent?’ Simon stared at her blazing granite eyes, wide and unblinking in her white face. ‘Tell her, Annie. She needs to know. We’re not children any more and neither is she’. Annie nodded. He was right. ‘She wasn’t sent to Purgatory, Morag. She chose to be there, to help the poor people who were suffering so much. She was doing her best to give them some support. They needed it so badly!’ she said in anguish, remembering the terrible things they had seen. ‘That’s my mum all right. She would do that. But what did she say?’ Simon pulled out his notebook. ‘We only talked to her for a short time, but I’ll tell you her exact words, because I wrote them down. “She will not dwell in the past, in grief. I want her to live her life, on her own, without a burden that will hang over her. She must make her own path, free from anything that might hold her back. I am gone from her. I am dead. She has to realise that. I will not be a shadow behind my daughter, constantly following her footsteps in life! You may think I am a cruel mother, but I am a faery. I know what will be right for her, and I will not stand in her way. Her path and her destiny is hers, and hers alone. She has to realise that”. Simon stopped, thinking of those words that had seemed so harsh. Morag sat still, her shoulders slumped. She began to sob soundlessly, tears trickling down her cheeks, leaving faint black marks as her mascara ran. Simon moved to comfort her, but Annie shook her head. Instead he pushed a box of tissues over. Morag took one and dabbed at her eyes, then stared at the faint dark marks on it, crumpled in her hand. ‘Excuse me, I need to go to the bathroom’. She got up and stumbled blindly through the door. ‘Do you think she’ll be all right?’ asked Annie, nervously. ‘I think she will’, replied Simon confidently, though he was not at all sure. It was ten minutes later when Morag reappeared at the door. She looked composed and serious. She walked silently over to the bed, sat down, threw herself back onto her elbows and began to giggle helplessly! Simon and Annie looked at each other in consternation. ‘Morag…’ ‘You pair of silly sods!’ ‘What… sorry… I don’t understand…’ Simon stammered. Annie’s mouth was open in confusion. ‘You idiots! You just gave me the best news I ever had!!’ Both their mouths hung open now. ‘I think I’d better explain’. Morag hoisted herself up more comfortably on her elbows. ‘She was saying, she really, really loved me, and giving me her blessings! All that stuff about burden and shadow, following my own path, was her way of doing that. It’s a kind of mother-daughter code that we had since I was about eight. I must admit that my mum had a rather odd way of conveying her feelings. She must have thought that you would give me the message without knowing what it meant, only you didn’t, to spare my feelings’. ‘We’re truly sorry, Morag. We didn’t know’ ‘You weren’t meant to. Only she and I knew’. Morag paused. ‘She obviously thought you were genuine, but didn’t know you well enough to tell you what she really meant. Thank you, Simon, Annie’. She sat up, cross-legged. ‘This really means so much to me’. ‘So, all this time, we’ve been worried sick about you and how you would react and…and…’ Simon spluttered indignantly. Morag leant across and stroked his cheek. ‘It doesn’t matter, Simon. Though I wish you’d told me before’. She looked across at Annie. ‘Don’t look so miserable, little sister. I’m all right. I’ve come to terms with losing my mother now. I’ll probably go home and have a little weep to myself, but I feel at peace. However, I do want to know something. How on earth did you get into Purgatory? Not many of us lesser mortals can do that’. ‘It’s a long story’. Simon sighed. ‘Anyway, we’ve told you and the rest of the Brotherhood already’. ‘And Sisterhood’ added Annie, mechanically. ‘ I probably wasn’t listening at the time. I wasn’t particularly happy, if I remember’. ‘Well, Nicolas Flamel put us in touch with a guide, who said he could get us in. We met him on Brighton Pier, playing the machines. Then he got us to see the Dance of death in a graveyard, with skeletons, so that we could get an image macabre that would get us there, which we did, by accident. Then…’ ‘Hold on. You went to see dancing skeletons and music and everything, then you got hold of this image thing…’ ‘This guide had secret photos taken of us for identity purposes…’ ‘I’m not sure that’s strictly legal’. ‘Anyway, we met up on the beach early one morning, and he took us to Purgatory. In a little rowing-boat, called Daisy’. ‘Daisy! A little rowing-boat!’ ‘You heard! That’s how we met your Mum!’ ‘I don’t think I will ever forget that awful place’ Annie whispered, her face torn in misery. Despite her apparent scepticism, Morag knew they were telling the truth. This was no fantasy. ‘Who was this guide? Did my mum know him?’ Annie giggled. Simon laughed. ‘I doubt it. A skinny little punk, with bits of body-piercing here and there. His name was…and you probably won’t believe this. Cosmo! ‘Cosmo!’ ‘Cosmo Hermes, to be precise’. Morag burst out laughing. ‘But he was a really good lad’, Simon added, hastily, ‘and looked after us, even during our so-called interrogation by Captain Zeno’. ‘A jumped –up stupid little schizo squirt, Zeno, I mean, who hadn’t a clue. He stamped our documents, before he fell over screaming. You’ve still got them, Simon, haven’t you?’ ‘Yes. I have. Do you want to see them, Morag, as proof?’ Simon said, pointedly, reaching for a file. Morag looked startled, realising that she had seriously irritated them both. ‘No, no, Simon. I do believe you. Even the bit about Cosmic Herpes, or whatever he’s called. Only that I don’t think anyone else will, outside the Brotherhood and Sisterhood. My Mum’s words have given me enough’. ‘Do you remember Venus?’ Annie asked, sharply. ‘Venus?’ ‘She was a skinny little girl, with long brown hair, and legs like matchsticks’. Simon said, rather crudely. Morag’s eyes widened in recognition. ‘Of course I do! We used to play together!’ She sat upright. ‘She was my Mum’s little waif! Mum rescued her from whatever you might arguably call a family, who’d just discarded her. Mum tried to feed her up, but she always went and threw it all up in the bathroom. She had severe anorexia, because no-one loved her, only my Mum. She looked after her, as best she could’. ‘She starved to death. She was with your Mum in Purgatory’. ‘Morag looked down at her hands clasped together. ‘I’m glad she is. I know my Mum would always look after her, even after death’. She looked up suddenly. ‘Do you think that Purgatory is a place where people, who have died before their time, go, until someone or other decides what to do with them? Do they have a second chance?’ Simon and Annie remained silent. ‘Stupid question, I know. Look, I must be going’. she got up suddenly, causing Simon to tip over on his side. ‘I’ve got work tomorrow. Annie, your project’s going to be really good, I know it. See you both soon’. ‘Wait! shouted Annie as Morag was turning the handle of the door. ‘What about your father! Do you remember him?’ Morag froze, her hand still on the door-handle. She turned around and looked at both of them, steadily, her dark eyes glistening. ‘No, I don’t. I wish I could. I don’t know even whether he’s alive or dead. That’s the truth. I must go’. She opened the door and went out. They both continued to stare at the closed door. ‘Well, that’s it. Another ripping adventure, and let’s go home for tea’. Annie turned to look at him. ‘You know that we can never go home for tea again’. she said, sadly.

*************

Simon woke up next morning to find a wailing banshee in his bedroom. At least, that’s what he thought it was, after a night of turmoiled sleep. Instead, it turned out to be his dearly beloved sister, Annie, who was rampaging up and down over his already over-strewn bedroom, picking up discarded clothes and throwing then down again, for no apparent reason. ‘Whassamater?’ he croaked. The fearsome banshee thrust two sheets of paper, stapled together, under his nose. ‘Read that!’ it screamed. Simon, who was in no state to read or even argue, gaped blindlessly at it. Eventually he made out a few words. “End of term Project results”. ‘So what?’ It was the wrong thing to say. The banshee began to gibber again, and finally he began to rise up from the submerged depths into a semblance of consciousness. ‘It’s Saturday!’ he said accusingly, ‘at the crack of dawn’. ‘It’s eight o’clock in the morning, you moron!’ the banshee hissed at him. ‘Read it, or I’ll throttle you!’ He fumbled at the paper that had been so rudely thrust into his hands. He turned the page over, and looked at the bottom of the second page. ‘Annie!’ he cried in delight. ‘You got an “A”!’ ‘Never mind that! Look at the comments!’ Simon decided to assert himself. ‘No! Not until I get dressed and have a cup of tea. I will then give you my measured opinion’. ‘Right!’ his lovely sister snarled. ‘You do that. Here’s yours!’ and threw a brown envelope at him. She stomped out, slamming the door behind her. Simon groaned. The beginning of a bad day, he thought. Annie in a raging fury. Just what I need. He opened his letter. Ten minutes later he emerged into the kitchen. Annie thrust her letter, and a mug if tea across the kitchen table towards him. She was still seething. ‘Read it! she commanded, furiously. Simon glared at her, and then looked at it. “Ms Wheeler has certainly used her fertile imagination, though it is unlikely, and inappropriate that she has chosen to present her hypothetical land in such a barbaric and military fashion. I do not understand why she seems to cite the male-dominated role of warfare as some kind of model for any civilised country, imagined or otherwise. Such a concept is totally unacceptable, though she has, at least, provided a role for women as equal to men, and rightly so, including a matriarchy, which is, in present-day terms, highly commendable, in relation to the demographic proportion of present society….” ‘I see what you mean. But, don’t forget, Annie, she’s never been there’. ‘But why should she represent any society as some kind of battle between men and women? Equality was just accepted as natural in Hyperborea! None of this rubbish about Eve being created from Adam! Women having to fight for their rights all the time! That’s happened in our world! Men and women as equals is normal in Hyperborea! Why should she always judge other worlds by the standards of our own? Its our world that’s wrong, not theirs! Stupid, politically correct bitch! Always judging other people by her own narrow view! Doesn’t she realise that other lands have other ways? Its pathetic and arrogant!’ ‘Don’t over-react, Annie. She just hasn’t realised that other worlds, and other peoples have their own ethical standards and moral principles, sometimes different from our own. Why should she? Unlike us, she doesn’t know that Hyperborea really exists. What she sees is the filthy mess we’ve made of our own world. She’s just trying to find a path through it, just like we are’. ‘I suppose so. I just don’t like this conceited, self-righteous way people have of doing it’. ‘She’s just trying, Annie, like we all are. Where’s the rest of the mail?’ ‘Oh, no, I forgot!’ She began to riffle through the pile of mail on the kitchen table, and gave a cry of joy, as she pulled out two small brown scrolls, tied with red string. ‘It’s from Helios! And this one’s from your beloved Ragimund!’ Simon snatched it from her, eagerly. Annie was crying quietly, as Morag had done the day before. She lifted her head and stared at him. ‘Does yours say the same?’ she asked, very quietly. Simon finished unrolling his parchment, and spread it out. ‘I’ll leave out the soppy bits. “Simon, our enemy has now declared war on us. They are marching with a mighty army against our western defences. My sister, Gloriana, has declared a state of emergency, and full mobilisation. We are now at war, Simon. This was not our doing. But we must defend ourselves to the very last. I pray that you and your sister may be able to come and support us, if you can. Our land, our home is at stake. We need every ally we have……”’ Simon put his head in his hands in misery. ‘Helios says very much the same’. Annie sniffled. The doorbell rang. It rang again, insistently. They remained at the table, listening to the sound of their mother walking down the hallway, and opening the front door. The sound of voices floated through, one soothing, the other agitated. They knew who it was. Morag burst through the door, looking slightly distraught, in her dark CID trouser suit and white open-necked shirt, her radio flapping against her hip. ‘Have you heard!’ and stopped as she saw the open scrolls on the table. ‘I see you have’. She slumped down at the table, opposite them. Their mother had entered silently, and glanced down at the table. ‘That is bad news, isn’t it?’ She pulled up a chair, sat next to Annie and hugged her fiercely. ‘Tell me’. She coaxed. Annie, muffled in her shoulder, whispered, ‘The faeries have gone to war, Mum’. ‘What!’ She looked up angrily at their father who had just come in. ‘Why didn’t we know this? We are still Watchers!’ ‘We both know the reason why. I fear there is more. A very large seagull dropped this on the doorstep, just as I was picking up the milk-bottles, and then flew away. It’s addressed to you’. He handed it to Simon. ‘It’s from the Brotherhood!’ he cried. ‘It’s sealed with the image of the Hand’. He tore it open, and then his face crumpled. He put it down slowly. ‘I’ll read it to you. “Annie, Simon. We have terrible news. We will be attacked tonight! Doctor Wrist and his family are planning a siege of our headquarters! They wish to destroy us once and for all! We know this from our spies. We have sent out messages to everybody to gather here, to fight off this great threat. This is not a false message. Adrian is delivering it to everybody, including your friends. We need your talisman, and that of Morag’s too. Come no later than five. Bring weapons! Signed, the Four Fingers”. Annie burst into tears again. Everyone else sat or stood, silently. The light had dimmed, still gleaming on the scrubbed table-top, that shone luminously, the edges and rims of mugs and plates glistening, scattered across its surface. A speeding car droned in the distance. ‘I have to go now. I’ve got a job to do. I’ll see you later’. Morag disappeared through the door. ‘I’ll see you out’. called their father, as he followed her. Morag was just opening the front door, when she felt a warm hand on her shoulder. ‘What are you going to do, Morag?’ Mr Wheeler asked gently. Morag turned to face him. ‘I’ll be there’. she replied quietly. ‘You can count on it. I’m sorry for leaving so quickly, but I couldn’t bear the sadness in there. It upsets me’. ‘I understand’. Mr Wheeler smiled. Then he frowned. ‘Morag, I must tell you something. I didn’t want to add anything even worse in there. My wife and I are no longer Watchers. We have resigned’. ‘But you can’t do that!’ exclaimed Morag, horrified. ‘They won’t let you!’ ‘We’ll see about that. Please keep this to yourself, Morag. We can trust you. After all, you have become part of the family, now’. Morag smiled sadly at him. ‘You’re the only family I’ve got left’. she whispered. ‘You’d better go. I must call my wife. Like you, we have things to do before tonight’. Morag turned and clattered down the front steps. Their father watched her get into her car, and drive off. Simon and Annie sat next to each other in the kitchen, lit only by the grey sky, scumbled through the half open blinds that cast a shadowy pallor over the cupboards and stove. They held hands to comfort each other. ‘The enemy outside and the enemy within’. Simon muttered. He looked hard at Annie. ‘Will you promise me something?’ Annie nodded. ‘If I don’t survive tonight, will you bury me next to Annabelle? Just to, sort of, keep her company?’ ‘Don’t say that, Simon!’ Annie cried sharply. She managed a rather wan smile. ‘They can bury me next to you and her, as well’. Brother and sister sat listening to the rain, beginning its insistent patter against the window and the wet road outside. There was a distant rumble of thunder. A petal detached itself from one of the flowers in the glass vase on the table. It floated gently down to the tabletop, without a sound. ‘There’s going to be a storm’. Annie said, very quietly. ‘It’s going to break right over our heads’.

Frank Jackson (10/01/1) Word count - 10549

|

BACK

Annie’s revised may of Hyperborea.

Annie’s revised may of Hyperborea.