BACK

DR FRANK JACKSON, 59A, PRINCES ROAD, BRIGHTON, EAST SUSSEX BN2 3RH

TEL. mobile 07982 032974 text and images throughout copyright

|

|

The House

Dramatis personae The Brotherhood of the Hand, a small society, dedicated to mystery, consists of four elderly men, in equally elderly grey suits, who correspond to the fingers of the human hand. Simon and Annie, brother and sister, have become members of the Brotherhood, as have their friends, Indira, Pei-Ying and Mariko. There is also Adrian the seagull and Sniffer the dog, the eyes and nose of the Brotherhood. A new member is Morag, half-policewoman, half-faery. Together they fight a war against their arch-enemy, Doctor Wrist, and his family, both past and present. The scene is the seaside city of Brighton. **********

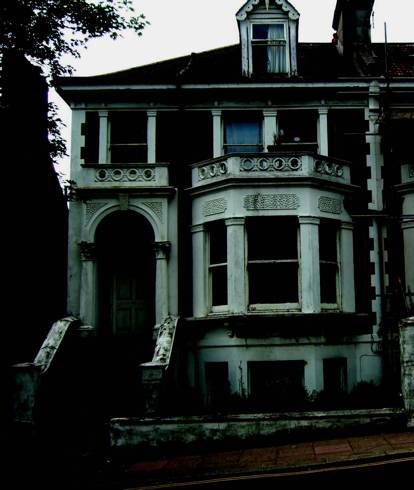

The house looked any other house in that street. It was a long road, stretching down towards the southern seafront in Brighton, consisting of large semi-detached houses on the right-hand side, looking east, and on the other, even larger detached houses, some still with their verandas above their windows. This house was one of those semi-detached ones, a late Victorian house, that still retained some of its external ornaments, with Corinthian columns framing the front porch, some parts of its acanthus leaves missing, tiny terraces in front of the upstairs windows, faced with gaping oveoles, and sculptured brackets underneath the windows. It was not a very inspiring house. Despite its size, it was dirty, and decaying, uncared for, and very shabby. Paint had peeled off its exterior. Though its brickwork was painted a rusty-red, the white stone trim and paintwork had turned grey with dirt and age. The large bay window, and that of the basement below it, was closed off from the world by old, equally grey curtains that made the house look as if it were, itself, aged and blind. It was not just this that had led Simon and Annie to stand on the pavement outside, staring up at the exterior. It was not just that the house itself seemed to hold secrets, that it seemed to embody a latent anger, as if it was holding its temper with difficulty, ready to lash out at others. Nor was it the uncared forlorn aspect of a down-at-heel gentleman, bearing the heavy toll of life, that intrigued them. It was something far more mundane, but puzzling. The house had no number. ‘I thought all houses had to have a number, or at least a name. Aren’t they supposed to be registered or something, Simon? How do they expect to get any mail?’ ‘I’ve no idea. It’s really strange. Come to think of it, I’ve never really noticed this particular house before. It was only when we were counting down the numbers as we passed, that I realised it. Part of my innate curiosity’. Annie still stood hesitantly in front of the steps leading up to the grimy front door, inside the porch. ‘I’ve got a strange feeling about this house. As if I’ve seen it before, in a dream. Or maybe, in a nightmare’. She suddenly shivered. ‘It’s not very friendly, is it? It makes me feel as though someone has just walked over my grave’. ‘Annie! That’s not a nice thing to say about someone’s house!’ ‘Well, how do you know it’s someone’s house? It doesn’t look like it’s been lived in, at least not for a long time. It looks really neglected, as if it’s waiting for somebody, or something. Well, I’ve decided’. ‘You’ve decided! Decided what, if I may be so bold, dearest little sister?’ ‘It’s time we honed up our detective skills. I would suggest, as your dearest sister, that we repair forthwith to the nearest estate agents, which is just up the road, and make enquiries’. She complained, hotly, ‘Just because you got there first, and popped out just before I did, doesn’t make you my elder brother. In any case, the last one out is always the best. So there!’ Simon knew better than to argue about birthrights with Annie. ‘Lead on. Let’s find out’. The bell rang as they went in. The young estate agent looked up as they came in, with a smile of welcome, though he was not expecting any business from them. ‘Good morning.’. said Simon grandly. ‘My child-wife and I would like to enquire about a house that we might purchase’. Annie glared at him, in fury. ‘Hello Simon, hello Annie’. said the young estate agent, completely unperturbed. He knew their sense of humour well. ‘To what do I owe this pleasure?’ ‘Can you tell us anything about the house down the road?’ Annie asked, deciding to take the initiative from her infuriating brother. ‘The one that doesn’t have any number’.

The young estate agent frowned, and looked puzzled. ‘It’s down Ditchling road here, isn’t it? I’ll just have a look in our files’. He went over to one of the large grey filing cabinets at the back of the office, and began to sift through the documents inside. Then he shook his head, and sat down again behind his desk. ‘I don’t understand it. There’s no record of any house in that place that we have. It just doesn’t seem to exist at all. We always have some documents relating to every property around here. Why are you so interested in it?’ ‘We’re just puzzled about it. Why hasn’t it got a number? Surely it must have?’ ‘I agree. But houses don’t necessarily have to show it. It must be number 203. What I suggest is to check with the postal directories in the reference library. They must have it there. That’s all I can do. Sorry’. ‘Well thanks for your help, anyway’. ‘Not at all. Anything for you and your…child-bride’. He sniggered. Annie gave him a hard stare, and a very stony look at Simon, then they went out. ‘I suppose you thought that was funny!’ ‘I did actually. Anyway I think he fancies you’. What! Some spotty-faced little clerk1 Do me a favour!’ ‘Where are we going now?’ ‘Try giving your brain a bit of rest, since there’s not much left of it, and try concentrating on our destination. We’re going to the reference library, to check out that house! And if you say another word, I’ll give you a good slap! Got it?’ ‘Message received and understood. Signing out’. ‘Good!’ Brighton Reference Library was housed on the top floor of the museum and art gallery. It was a place that Annie always liked, partly because it was peaceful and quiet, with friendly staff, but also for its comfortable size and decoration. It had a very high ornate ceiling, with large tables and chairs that were just right for working on and spreading out maps and documents. The bookshelves were filled with volumes and records of Brighton’s local history, and among these were old postal directories, dating back well into the nineteenth century. They settled down happily with a pile of these to look through. After half an hour, they sat back and looked glumly at each other. ‘Well, we’ve been through right back to the First World War. But they haven’t really told us anything much. And the most recent ones have the number, 203, but no names of who lives there. the only trouble is, that there are three different directories – Kelly’s, Pikes and Towner’s, and they just haven’t got them all here’. ‘Why don’t we try a few earlier ones? Those houses were probably built in the 1890s. Might be interesting’. Simon wandered over to the shelves and came back with a small pile of bound directories. ‘Let’s see. Harrison, T. Dental surgeon. 1901, and 1902, and 1903’. ‘Harrison, T, 1904 and 1905’. ‘1906. Guess what? ‘Harrison, T?’ ‘No! The Reverend G. Wirts. Strange name. What’s the matter, Annie?’ Annie was looking at him with a strange look on her face. She began scrabbling furiously through the remaining directories, watched by a curious Simon. Then she stopped, and stared at the open books in front of her. She pointed at the one closest to her. ‘Towner’s Directory, 1907. There’s no name and no house number. They’re missing! It’s the same with 1908, 1909 and 1910!’ Simon picked up the next directory, and began leafing through it. ‘1911. It’s listed here! Otto von Helde, esquire, music teacher’. Annie was scribbling something in her notebook. She passed it over to Simon. He gasped. She had written: W. I. R. T. S. W, R. I. S. T. ‘An anagram!’ ‘Exactly. So why is Doctor Wrist’s grandfather, if it is him, living in Brighton at that time? Why does he start off as a reverend? To give himself a cover? Why does his name and house number disappear for the next three years? What was he doing?’ ‘Hold on. There are rather a number of flaws here. Firstly, it might not be registered because the occupants have changed. Secondly, it might be registered in another directory. Thirdly, it’s all too much of a coincidence’. ‘But that’s the point! It’s a secret address! He comes as a reverend, probably in disguise, because everyone trusted a clergyman at that time, then he mentions he’s going off to do missionary work abroad, and he’s going to rent his house out to a photographer friend, who doesn’t want to be disturbed, and so doesn’t register for the post, because he doesn’t want any, so he can get on with his dirty work, capturing people and ruining their lives, just because he enjoys it!’ ‘Excuse me, try keeping the noise down a bit. This is a library’. Annie looked up at the young librarian. ‘’Oh, I’m really sorry!’ she stammered in embarrassment. ‘It’s just that we’ve discovered a big secret’. ‘Well, try to keep your secrets a bit quieter in future’. He grinned, winked at Simon, and then walked off. ‘There you go again, Annie’, remarked Simon wearily. ‘showing me up in front of the public servants’. ‘Shush. This is a library, remember? Let’s put these books back. I want to have another look at that house’.

***********

They stood on the pavement outside and stared hard at the house, both thinking about what secrets it might hold. It still looked forlorn and decayed, and seemed almost to glower back at them. ‘It’s not a very happy house, is it?’ remarked Simon. ‘There’s no-one around, is there?’ ‘No. Why? He looked suspiciously at his sister. ‘I just thought I might take a little peek through the letterbox’. Before he could object, she darted up the steps, knelt down and pushed the letterbox flap. It was tight and rusty, but she managed to open it enough to peer inside the dim interior. It took both her hands to hold the flap open, and for a few seconds she could see very little. The Simon saw her body stiffen in shock. ‘What is it, Annie?’ he called anxiously. Instead of replying, she waved her hand to him to come and look. He looked around quickly, then went up the steps to the letter-box and pushed it open painfully. At first, he could see very little in the dark hallway. ‘Look to the right, where the mirror is, on the wall’. Annie suggested behind him. He peered again, and could just make out a large mirror, mottled and dimmed with age. There was something, a piece of paper, wedged into the frame. Then the letterbox snapped.

‘Owwww!’ he yelled. ‘It bit me!’ ‘What did?’ ‘The door! This house!’ He shook his hand up and down in pain, and glared at the door angrily, wondering whether to kick it. ‘Did you see the piece of paper?’ Annie asked urgently. ‘I saw it. Annie, you were right, after all!’ ‘Let’s get back and compare notes’. ‘And nurse my fingers! I hate that house!’ They sat together around the kitchen table, Simon still sucking his fingers. I’ll probably get rabies now’, he muttered gloomily. ‘Then I’ll turn into a screaming madman, foaming at the mouth’. ‘Well, that’s nothing new. Come on, Simon, try to remember what you noticed about that handbill. At least, I think that’s what it was’. ‘It was old’. ‘I know that!’ ‘It was sort of yellow and faded. It looked very old-fashioned, like some of those old Victorian and Edwardian adverts. I could only see a few bits of what was actually written. Something about “modern photographic apparatus” then something, something “family portraits”, “privacy of your own home”. What else? No, I remember! “likenesses guaranteed” Then there was a photograph, or what looked like it, on one side. But it was too dark to see properly’. Annie was scribbling furiously on a blank sheet of paper, then stopped. ‘I’ll add in what I saw’. she said grimly. ‘Then we can put it all together and see what we’ve got’. She began to write furiously again, while Simon tried hard to think of anything else he could remember, though nothing further came to him. The hallway had been too dark to see further than a few feet into its gloom. A few minutes later, Annie passed over the sheet of paper. She had written out part of the handbill. Simon looked at it. Geo. Wr ___ Photographer

? Family _____ Portraits_______ A Speciality Accurate __________ guaranteed! Modern photographic apparatus No Studio required. Charges_____________________ _________mounted and framed

To be found at_________________________

‘What do you think?’ asked Annie quietly. ‘Do you still feel I’m wrong?’ Simon stared at the incomplete advertisement, thinking hard. ‘No, I don’t think you’re wrong at all any more. I just couldn’t understand how or why Doctor Wrist’s grandfather should hide himself down here. But I think a lot of photographers at that time must have moved down here from London, and set up business. But we didn’t see any address, did we?’ ‘ No, but it must be that house! How else would we have seen the handbill?’ ‘I know, But, Annie, something really worries me about that house. There’s something very wrong, and I don’t know whether it has anything to do with magic, or fantasy. But I don’t think it’s real! At least, not in the way that we would know it! Can I tell you what I believe? You might not like it’. ‘I think I already know what you’re going to say, Simon. But say it anyway. We need to know what we’re up against’. Simon leaned back, with his hands behind his head. ‘That house is haunted. It doesn’t belong there anymore. It’s a house that has come back from the past, which no-one, apart from ourselves, even notices or sees. Why? Has it come back for some purpose? Or is it’, he paused, ‘ a place where really bad things have gone on inside? Is that why it seems to have come back from the past, as if it’s haunted itself? It doesn’t exist here! It shouldn’t exist here! It’s malignant, a nasty presence that has no place here now!’ ‘And what’s your conclusion?’ Annie asked gently. ‘We need to exorcise it. To send it back to its own time and place. To let it rest in peace where it belongs’. Annie was silent for a few moments. Then she spoke, quietly and sincerely. ‘I agree with everything you say, Simon. You and I think the same. It’s not the house I’m frightened of, even though it is malignant and carries a sense of evil about it. But I don’t blame the house. I blame the people that used it, for their own twisted ends!’ She was silent again for a moment. ‘You know what really makes me so angry? Because Doctor Wrist’s grandfather not only destroyed Rosamund’s family, and almost certainly others, but they actually charged them money for it! How callous and vicious can that be! That grandfather of his must have enjoyed that so much!’ Annie’s voice was loaded with venom and sheer fury. Simon looked at her, and then looked away. “I think that you and I should take on a little spot of burglary tonight. I suggest that we should take a very good look at the inside of that house. I’m not happy. I want to set this straight once and for all’. Annie gaped at him. For once, she could hardly find words to speak. ‘Simon, you’ve just pinched my line! Are you serious?’

He gazed up at the ceiling of the kitchen. ‘Yes, I am. Believe it or not, Annie, I care about Rosamund and her family. You don’t have to tell me, because I know already. Her family were destroyed by the creature that lived in that house, and she survived to become a faery, only to die in our battle. Our battle, Annie. I don’t like revenge, and you know that already, but I do care about justice, and I do care about doing some good in this world. So that’s where I stand. All right?’ Annie just sat on her kitchen chair in amazement. Then she finally managed to ask something. ‘Simon, aren’t you frightened of this? Of going into the unknown?’ He burst out laughing, and then groaned piteously. ‘Of course, I am! I’m absolutely terrified! Anyway, are you coming, or do you want to stay at home?’ ‘You complete, utter idiot! Ask a silly question!’ ‘I take it that’s a yes’. Annie was silent for a moment. ‘Are we going to tell the others?’ ‘The Brotherhood of the Hand, you mean? I don’t think so. If we’re going to perform a spot of burglary, we shouldn’t involve anyone else’. ‘Not even Morag?’ ‘Definitely not Morag! If she knew, then she’d do her best to stop us. She’s a policewoman, remember? She’s got a career ahead of her, which we can’t jeopardise. Anyway, she’s been through enough for the time being’. ‘So it’s just you and me then?’ ‘I guess so. We can always make up a cover story, if we get caught. We could just say that we were passing by and saw something suspicious, so we went to investigate. That’s more or less true, any way’. ‘In the middle of the night?’ Annie asked sceptically. ‘Well, we both suffer from insomnia, don’t we? You wanted to go for a walk, and I came along as a dutiful brother to protect you’. ‘Ha!’ Annie snorted. ‘More like the other way round’. ‘Whatever. Shall we make it midnight? Mum and dad will have gone to bed by then’. ‘Until they get woken up by the police banging on the door, holding us by the scruff of the neck, arrested for trespass and burglary’. ‘All the more reason not to tell anybody else about it, then. “It’s all right officer, they were just sleepwalking. They do it all the time”’ ‘Hmmm’, was all Annie could think of, in reply.

*************

It was nearly one o’clock by the time they set off. Not only had their parents gone to bed later than usual, but they had had their usual squabbles about what to take with them on their nocturnal expedition. Annie had firmly quashed Simon’s ideas about taking bolt-cutters, hacksaws and crowbars. ‘No you can’t! They’re too heavy, make too much noise, and they provide incriminating evidence! “Oh, yes, officer, I was just sleepwalking and I found myself in this strange house with this bag of housebreaking tools. Can’t imagine how they got there”. I can just see the police buying that one!’ She also firmly vetoed the idea of wearing balaclavas (‘Too itchy!’) and of blackening their faces (‘It’ll ruin my complexion!’) In the end, Simon had to settle for dark jeans and sweaters, a small screwdriver, and a small Swiss army knife, with various attachments, one of which, Simon claimed, could extract stones lodged in horses’ hoofs (‘Very useful. Just the thing if we meet a faery on her horse. We can offer her a bit of on-the-spot maintenance for her trusty steed’).They also carried their heavy torches. The torches however, were essential. Nearly eighteen inches long, powered by six large batteries, they could be focussed from a wide glare down to a narrow beam of light. Being heavy, they were also useful as a weapon, as Simon and Annie had found in the past, when attacked by their enemies. So it was a lightly equipped patrol force that went out that night, to find out the secret of the mysterious and unnumbered house. As they drew nearer, the house seemed to grow larger and larger, and, as they stood outside it, became a huge forbidding fortress. The street-lights seemed to emphasise the shadows that it cast. The windows gaped at them like empty eyes. The front doorway was completely dark. They both shivered. It had been one thing to sit at home in a warm kitchen and plan their strategy. It was quite another, to be confronted with this cold, dark bulk, that seemed to breathe a stench of foreboding. Annie hesitated a moment, then quietly went up the front steps, and, reaching through the darkness, found the doorknob. She twisted it. It was firmly locked. She retreated down the steps and shook her head at Simon, who motioned with his hand to the side of the house. There was a broad passageway along the side of the house, but still dark and shadowy. Under the front steps, on the right, was a small panelled door, grimy and worn. ‘That’s to store the coal in, for heating’. Simon whispered. Annie nodded. She didn’t feel like speaking. There was the sudden sound of a car approaching. They flattened themselves quickly against the side of the house. For a moment the car’s headlights illuminated everything and then it was gone, the noise of the engine receding in the distance. The wall felt clammy and cold against their backs. Simon breathed out, and then shone his torch briefly ahead. ‘A great big wooden fence. It must be about eight feet high’. He walked up to it and began to feel his way along it. Then her stopped and came back to Annie. ‘There’s no door at all. It’s too high to climb’. Annie felt behind her. She felt wood, not brick. ‘Simon’, she whispered. ‘There’s another door here. It must lead into the basement’. She felt cautiously along the side of the door, and felt a cold metal handle. She turned it. There was a slight creak, and the door opened inwards with a slight creak, for about two or three inches. They stared at each other. The door was open, but to what? ‘Are we, or aren’t we?’ ‘We are’. With that, Simon pushed the door open and moved cautiously inside. Annie followed him, feeling the damp musty air of an old and forgotten room. They stood inside what was probably once a kitchen. Large wooden counters, grey with dust, ran along two sides, with a white ceramic sink, festooned with cobwebs, in the corner. Facing them was a filthy dilapidated gas range, its burners red with rust. The floor was paved with stone flags, barely visible through the layer of grease and grime that covered them. The whole room smelt of decay and rot. They shone their torches around, taking care to make sure the beams of light did not show through the front window. ‘There’s another room at the back there. That must be the scullery, where they did the washing and laundry. There’s even an old dolly-tub in the corner, where they washed the sheets. That little room over there must have been the larder, where they kept the food cool. No refrigerators in those days’. ‘How do you know all this, Simon?’ asked Annie. It was partly out of curiosity, and partly to offset the feeling of dread and gloom that had descended on her, now that they were inside this terrible house. ‘Just reading, I suppose. I’ve always wanted to know how people before us lived. There’s a small narrow flight of stairs there. It must lead up to the main rooms’. They began to walk slowly and cautiously up the little winding staircase, leaving footprints in the deep dust on each tread. Annie didn’t want to look up. Instead she concentrated on each step. She glanced at the talisman she wore. It was dim and lifeless. Not even a faint glimmer. ‘Simon’, she whispered. He paused. ‘What?’ ‘The talisman doesn’t seem to work here. Have you still got…Ragimund’s stone?’ ‘Right here’. he patted his pocket. ‘Come on. We need to look upstairs’. At the top of the stairs was a small door. Simon gently pushed it open, then waited for a few seconds. There was not a sound to be heard anywhere. It was as if the house itself was holding its breath. Then they moved quietly from under the stairs into the hallway. It was even darker here than on the stair. No light filtered from outside. Annie could just about make out a dull glimmer on the wall opposite, which she realised was the mirror, and a small yellow shape. ‘There’s the handbill!’ she whispered, and pulled it out from the mirror frame. As she tucked it into her pocket, she realised that she had unconsciously avoided looking at the mirror itself. ‘Shall we try upstairs first?’ whispered Simon pointing at the stairs, that went up the left-hand wall. He began to walk slowly up. The silence hung around them like a shroud, as if they could literally feel it. The stairs were carpeted, but like everywhere else, were grey with dust. They paused on the half-landing. Before them was another short flight of stairs, at right-angles to the ones they had just climbed. They led to another landing with three doors opening from it. As they mounted the stairs, they saw another door at the end, towards the back of the house. ‘Three bedrooms and a bathroom’. muttered Simon. He was trying to keep his bearings in the gloom of the house. On the left-hand side of the landing was another small, narrow staircase, that led up towards the roof. Annie tugged on his sleeve. ‘I want to see what’s up there! Don’t ask me why! I just do!’ Something was telling her that there was something important and terrible upstairs. Simon looked at her dim shape with surprise, and then shrugged. He carefully began to walk up the little narrow staircase. There was no carpet here, only bare dirty wood, that creaked and groaned slightly under their feet. It led to a small panelled door, which was also unpainted, and cheaply made of pine planks. There was a small latch and something else next to it. Simon shone his torch at the door. ‘It’s a lock! But it’s on the outside! Why?’ ‘To keep someone a prisoner perhaps?’ whispered Annie. ‘What is this room anyway?’ ‘It’ll be a servant-girl’s bedroom. They always put the servants up in the roof. Oh, no!’ Annie stared at him. His eyes were wide with fear. ‘I hope she’s, she’s not still in there!’ Annie gulped. ‘We’re just going to have to find out, aren’t we?’ She pushed past Simon and tried the door. It opened. She pushed it open and they peered into the room. There was no-one there. They looked around at the tiny little room. They could see, from the glimmers of light from the street-lamps outside, through the bare dormer window, that it was very small, only about eight feet square. There was very little furniture. Along the left-hand wall was a small iron framed bed, with an iron bedhead. It was covered by a thin, grubby mattress. On the other side, close to the window, was a little washstand with a bowl, and a china jug, both of them chipped and cracked. Hanging from some nails on the wall opposite the bed, were some rusty coat-hangers. A filthy little mat partly covered the bare floorboards. ‘Whoever the servant was, she didn’t have very much. Nothing personal, no pictures or anything like that. It’s just like a prison cell……’ He broke off suddenly, his torch focussed on the metal bed-head. ‘What is it, Simon?’ cried Annie anxiously. ‘What have you found….Oh, no!’ She gave a strangled little cry of horror, as she saw what Simon’s torch had revealed. Locked around one of the uprights of the bed-head was a set of iron manacles, joined together by a chain. The manacles were joined together by two small padlocks, that would imprison the wrists tightly. They were old and rusty, but still looked cold and cruel. Annie stared at them with anger and revulsion. She could imagine a young frightened girl, locked to the bed, with no means of escape, crying, miserable, alone in the dark at the top of the house. Simon bent over and picked up something from the floor. With an effort, Annie pulled her gaze away from the manacles, and shone her torch on the thing that Simon held in his left hand. It was a old wooden ruler, about a foot long. As Simon turned it over, they both saw some brownish stains along the back. ‘It’s what he used to beat her with’. Simon said, in a very cold, hard voice. ‘He must have really enjoyed it’. Annie began to sob very quietly. ‘Poor little thing. She was probably younger than us, in her first job, not even knowing that she was going to work for a depraved monster like our Mister Wrist’. ‘Put it down Simon. I’ve seen enough. What was that!’ They stood and listened. There was something moving about downstairs It was a skittering, pattering noise. Then it stopped. Then they heard a low rumble. It ceased. Then it started again, and ceased. Then there was another. Silence descended. Annie walked as quietly as she could towards the door, and listened intently. At first she could hear nothing for a few seconds. Then she heard it again. It sounded like heavy breathing, like the moving of the wind over the sea. And she could also hear another lighter breathing sound, between the heavy breaths. Then there was another small pattering sound. It stopped. She looked back at her brother. ‘Simon, we’ve got to get out of here! That wasn’t rats or mice! It was something else!’ She pulled hard at his arm. Simon was still looking at the bed, his face pale in the dim light. ‘Simon! For goodness sake! Let’s get out, now!’ She dragged him forcibly towards the door. Simon looked around at her. ‘What?’ he said blankly. Then he realised. He heard the sounds for the first time. They went down the stairs, carefully, their unlit torches in front of them. For the moment, all was silent. Simon stopped at the foot of the stairs. ‘We need to check the bedrooms!’ he hissed in her ear. ‘His laboratory, or darkroom might be there!’. There was no sound any more. Just a heavy, enveloping silence. Simon pushed the first door open. He gasped. Annie peered over his shoulder, after looking around behind her. She gasped, too. The room was filled with large wooden benches, covered with strange dusty glass beakers, retorts, and globes, some of them mounted on small iron tripods and small metal frames. Some contained a dark mouldy liquid. A small Bunsen burner stood on a small table next to one of the benches. On another lay a small tank, now empty, for developing negatives or glass prints. But it was the lingering smell that prevented them from going any further. It was the strong, acrid smell of sulphur. Simon closed the door quietly. He stared at Annie. ‘That’s not a photographer’s studio. That’s an alchemist’s laboratory! That’s why he could capture people, through their likenesses, and make them do what he wanted! So he could destroy them! That’s what he liked! Power! And he enjoyed capturing them, so he could do what he liked with them! Except that Rosamund managed to escape! I think she managed to take his photograph, somehow, and got away because of that!’ ‘Simon, we haven’t got time!’ She was listening again to the heavy breathing. It seemed to come from the next room. She heard that tiny pattering sound. It seemed to come from downstairs. ‘We’ve got to get out of here, now!’ she whispered urgently. ‘Let’s check the next room, and then we go. All right?’ Annie nodded. She was just as curious as Simon. He opened the next door, and peered in cautiously. ‘This is his bedroom’. It was a large room, with a massive double bed, covered with a large stained mattress. A large rag rug lay on the floor between the bed and the door. Two small, rather flimsy painted chairs stood in a corner. Behind the door stood an enormous wardrobe, or armitoire, as Annie remembered it. The curtains that hung at the bay window, left the room in a twilight atmosphere. There was no sound at all, here, or from downstairs. Simon began to walk across to the bed. He could still see an imprint of someone who had laid there, on the mattress. The rug suddenly moved under his feet! He pitched face first onto the bed. The mattress reared up and enveloped him, folding over to imprison him like a trapped fly! As Annie opened her mouth to scream, one of the small chairs darted forward and behind her, so she fell backwards onto it. The other chair flew through the air and landed upside-down over her head, encasing her securely! The wardrobe doors opened wide with a loud creak and wooden grunt, its black interior gaping wide like an opened mouth. The chair on which she was trapped began to move slowly, inexorably, towards the jaws of the wardrobe! Smothered under the heavy weight of the mattress, Simon’s hand groped desperately towards his pocket. The weight on him was overpowering. It stank of damp, urine and, sulphur, that made him choke with nausea. His hand finally grasped what it was looking for. He pulled it out, and thrust it against the weight above. There was a terrible groan of pain, and the mattress folded over him, suddenly flew back. He rolled off the bed, stood up, saw the rumpled carpet and kicked it away into a corner of the room. Then he saw Annie, still thrashing and gasping, between the two chairs, being drawn towards the open wardrobe. He grabbed the bamboo legs of the chair above, and pulled with all his strength. The chair resisted, and then it came free. He hurled it savagely against the far wall, where it broke, disintegrating into pieces. Annie had leapt off the chair underneath her, seized it and threw it into the wardrobe. Its doors suddenly closed with a small shriek, and snapped shut. ‘Downstairs, now!’ They rushed out, and down the stairs, then stopped. Between them and the front door stood large grey shapes. They recognised them immediately. They were large wooden armchairs, heavily upholstered, their outlines barely visible in the dark atmosphere of the hallway. Annie looked down. Their marks led back to the doorway on their left, just behind them. Another armchair stood behind them, blocking off any escape from the back of the house. ‘Into the sitting-room! We can break a window to get out!’ shouted Annie. There was no reason for being quiet now. They rushed in and looked around wildly. Facing them was another enormous shape. It was a large upright piano. Towards the back of the room, something skittered on the floor. They could just see what it was – a small glass-fronted cabinet, with two glass shelves inside, and a mahogany frame. It scuttered for a few seconds on its four feet, and then climbed up the wall. It climbed up the wall. It pattered across the ceiling until it was upside-down above them. The piano began to rumble and move forwards. Neither Simon or Annie had any clear recollection of what or why they did next. But Annie hurled her torch, that she was miraculously still clutching, upwards at the cabinet. It struck it, splintering its glass doors. The cabinet screamed and fell with a crash onto the floor in front of them, upside-down, it’s brown mahogany legs, capped with claw feet, waved frantically in the air. The piano loomed over it. ‘Quick!’ shouted Simon. They ran around and began to tip the piano forwards. It was incredibly heavy. They pushed with all the strength they had. It began to topple forwards. It fell with a crash, and a jangling of piano keys onto the tiny cabinet, smashing it utterly. Small fragments of glass scattered across the floor. One of the small brown legs fluttered briefly and then was still. The piano uttered a heavy groan, and then settled. Dust rose in clouds in the room. But there were two other large armchairs, facing them, in front of the large bay window. They turned and ran back into the hall, Annie picking up her torch, that had fallen close to the doorway. The armchairs were still there, barring their way. They stood for a moment, helpless. Annie glanced sideways at the mirror. Her mouth dropped open. Then she screamed. It was her scream that made Simon act. He threw his own torch straight at the mirror. It splintered and broke, the shards of discoloured glass cascading onto the floor. A wonderfully sweet scent of something filled the hallway. It remained for barely a second and then disappeared. Simon fumbled in his pocket again, until he found what he wanted. ‘Annie! Give me the hand-bill! Now!’ She had collapsed into a kneeling position, but reached numbly around until she found the paper that she had taken from the mirror-frame. She handed it dumbly to Simon. There was a sharp flare of light. Simon was holding a small lighter under the handbill. ‘Let us out now!’ he shouted. ‘Let us out or I’ll burn this place down!’ He touched the lighter to the handbill. It began to burn from the bottom corner, the flame beginning to lick up, the paper charring in the heat. There was an absolute silence for two or three anxious seconds. Annie sat on her heels, staring ahead of her, rocking gently back and forth. Then the chairs moved. With a low rumble, they slowly moved aside to leave a small gap. There was a click, as the front door opened, and moved ajar. Simon seized Annie by her sweater and dragged her upright. Pulling her behind him, still holding the burning paper in his right hand, they squeezed through the gap, and through the front door into the warm night air. They stumbled down the steps. Simon dropped what was left of the burning handbill, and stamped it out. They heard the door close behind them. Simon suddenly saw a car with headlights coming up the road towards them. ‘Quick!’ he muttered and clasped Annie in a lover’s embrace. The car passed them but not without blasting its horn, together with a few jeers and catcalls. Then it disappeared. But Annie was still clinging onto him tightly. She was trembling violently. Simon realised something was wrong. He held onto her and steered her across the road, where they sank down together against the wall opposite. Annie held her face in her hands, her breath coming in long shuddering gasps. Simon, still feeling rather shaky himself, waited patiently for her to calm herself. She had seen someone in that mirror in the hallway, but what? Finally she put her hands down, and stared at him, her eyes large and dark in her pale face. ‘Simon, I saw a, a face in the mirror!’ ‘Perhaps it was your own reflection’. ‘No! No, it wasn’t! It was somebody else!’ It was a young girl’s face! She had her hair loose, and she was in some sort of nightgown, I think!’ Annie took a deep breath, while she remembered. ‘Her face was so thin and pale! And her hands! Her hands were pressed right up against the glass, like this’, and she stretched out her hands outwards to demonstrate. ‘She was trying to say something to me! I could see her lips moving! Images don’t move, do they? But this one did! Then you broke the glass, and she disappeared! But do you remember that beautiful smell, Simon, when that happened? It was so different from all the other smells in that awful house. It was almost…..fragrant!’ ‘I know. I smelt it too. But what does it all mean?’ ‘I don’t know. I’m too tired to think any more’. She looked across at the house. ‘It doesn’t look at all miserable now, does it?’ The house didn’t. In fact it looked shrunken, tired, an old grey man in his last years. The brooding menace seemed to have gone, dissipated in the soft night breeze. Simon looked at his watch. It’s well past two in the morning. We’d better go back and get some sleep’. They got up rather painfully, and slowly made their way back up the hill to their own house.

************

Annie got up late the next morning. She had slept badly. The image of the girl’s face had kept reappearing in her dreams, but she still couldn’t understand what the girl had been trying to say to her. Tired and still confused, she walked down the stairs towards the kitchen. On the hallway table, she found a note from their parents to say that they had gone shopping. She looked in the mirror cautiously. All she saw was her own face, with dark, sleepless rings under her eyes. On a sudden impulse, she picked up the telephone, and dialled a familiar number. She was surprised when she went into the kitchen. Simon was sitting at the table, a mug of tea next to him. several sheets of paper were spread out on the tabletop in front. Annie noticed with alarm, that he was still in the clothes he had worn last night. There was still a whiff of damp and decay around them. Annie poured herself a mug of tea, and sat down quietly next to him. ‘Simon, have you been up all night?’ ‘Yes. I couldn’t sleep’. He spoke in a flat monotone. Annie looked down at the sheets of paper, and gave a start. They were covered with doodles, of houses, and mirrors, and small plans of the house they had visited the night before. There was a single recurring word, heavily underlined, on every sheet –“WHY?” Annie looked up at Simon. ‘You’d better go and have a bath, and change’, she said softly. ‘Those clothes really stink. I’ve just arranged a meeting with the Brotherhood of the Hand. We’d better edit what we need to say, in case Morag’s there’. He nodded, got up and went upstairs. Annie stared down at the sheets again, full of alarm and anxiety. Why was he so low in spirits, and why was he so obsessed with all this business? It seemed to have affected him badly. He wasn’t, was he…? ‘Oh no!’ she groaned to herself. They had arranged to meet the others at midday. As they walked down towards the seafront, Annie tried to engage him in conversation, about what they should tell the others. But Simon ignored her. He carried on walking, his head down, his hands buried deep in his pockets. As they walked down New Road, past the library, he suddenly muttered, ’I’ve got to do something, I’ll catch up with you later’. Annie watched him go. He was walking in the direction of the museum and art gallery. A terrible feeling of anxiety welled up inside her. But she continued on towards the meeting-place. They were all there at their normal café table on the beach – The Four Fingers of the Brotherhood, their three friends, Indira, Pei-Ying and Mariko, Morag, half policewoman, half faery, Pat, the Irish scholar, his white panama hat at a rakish angle, the large bulk of Sister Teresa, smiling sweetly, Adrian the seagull, waddling about on the end of the table, hungrily eyeing any available scraps of food, and Sniffer the scruffy dog, lapping at a bowl of guiness, lying next to them. They greeted her with joyous shouts, that faded away as they saw her face. ‘Where’s Simon?’ asked Pat. Annie drew a deep breath. ‘He’s coming later’. ‘No he’s not’, replied Pat, turning around in his seat. ‘He’s coming now’. Simon walked slowly towards them, carrying something. Everybody looked at him as he stopped at their table. They all knew, from his tight drawn face, that something was terribly wrong. He dropped the piece of paper he was carrying onto the table in front of Annie. ‘Read that’. he said in a dull voice. Then he turned and walked away quickly. Annie stared at the photocopy on the table. She read a few lines, and burst into tears. She tried to get up from the table. ‘Simon!’ she shouted. ‘Simon!’ she shouted again desperately, But he was already lost in the milling crowds on the promenade above. ‘I must go after him!’ But Sister Teresa’ large hand grasped her by the arm. ‘No, Annie. You must let us all read this first, and then tell us how it relates to what you were both doing last night’. Annie sat down again, miserably. The others all crowded around to look at the document, Mariko’s arm comfortingly around her shoulders. It was a newspaper article, heavily ringed around in biro, and dated November 19th, 1910. “A DISTRESSING MURDER The Brighton and Hove police are investigating The corpse ,bearing the marks of frequent The case continues.” ‘Does this have anything to do with what happened last night, Annie?’ asked Index Finger. His voice was friendly, but puzzled. ‘Yes, it does. A lot’. ‘Perhaps you should tell us about it, Annie’. suggested Middle Finger. gently. ‘But what about Simon?’ cried Annie , looking around wildly. Sister Teresa suddenly grasped her arm firmly. ‘You stay here, and tell us what happened. This is worse than I thought. Morag, will you go and find Simon, and talk to him?’ ‘Yes, but why me?’ asked Morag, surprised. Sister Teresa smiled at her. ‘Because you and Simon understand each other’. Morag stood up. ‘All right. Don’t worry, Annie, I’ll find him. I think’, she said, glancing up at the crowded Brighton Pier behind them. I know where he’ll be’. She set off towards the promenade. Sister Teresa leant over towards Annie. ‘Trust me, Annie. She is the best person at the moment. Now tell us all that has happened to you’. *************

Morag walked along the pier on the eastern side, through the throngs and couples of people out for an afternoon on the Pier. As she passed the arcades, the bleeps, cries and general electronic hubbub rose and swelled, then subsided, the sea of noise receding to the undertow of soft rock music over the tannoy of the pier’s DJ system. No sign of Simon on that side. She turned around and walked along the west, back towards the shore. Then she saw him, halfway along, leaning on the rail, looking out at the sea. She stopped, and leant on the rail about a yard away. ‘Simon, it’s Morag. Can I talk to you?’ ‘Stay away from me!’ It was so sharp that she recoiled. Simon seemed to relent. ‘I’m not very good company at the moment’. ‘I don’t mind’. she replied. After a moment or too, she said quietly, ‘Come back down with me. Your sister’s really worried about you’. ‘Is she?’ Now or never. ‘Yes she is. Very distressed in fact. She thinks you’re going away from us, like she did. Are you?’ She could see it had jolted Simon. He looked at her, startled, and paused. ‘No. I don’t think so’. He looked out over the sea again. ‘Morag, Can I ask you a question?’ ‘Of course, you can. You know that’. ‘Have you worked on any serious murder cases yet?’ She hesitated. ‘Not as yet, no’. ‘If you uncovered a crime, a murder, which was so horrible, so cruel and sadistic, that it revolted you, what would you do?’ ‘Simon, if you’re talking about that newspaper report, that happened over a hundred years ago!’ ‘But what if the effects of that murder were still around, and you found it. like we did, last night? Wouldn’t you still feel sorrow and grief for what happened? Tell me, Morag! I really need to know!’ Morag turned and stared at the sea below. ‘I don’t feel that one can take the law into one’s own hands. I’m a cop. I provide justice, and the right of everybody to live their own lives. I can’t make life or death decisions’. ‘You haven’t answered my question, Morag. If the crime was so sadistic, done purely for enjoyment, for pleasure, without any care for morality or for the victim, what would you feel? What would your faery side do?’ ‘My faery side would probably tear them apart! Stop it, Simon! Why are you asking me this? It’s not about me, it’s about you! Why do you want to know?’ Simon sighed. ‘Because I want to understand why I feel such grief and hatred in me. What happened last night enraged me so much that I’m not rational any more. I’m not walking away. I’m just trying to make sense of how angry I am, and what I can do about it, and I really don’t know why or how!’ Morag was silent for a moment. Then she put her hand out onto Simon’s arm. ‘I do understand. I’m not sure whether I would be able to control my own anger, and my faery anger, in such a situation. But I do have a suggestion’. ‘What is it?’ ‘Find out the name of this young girl. At least you can give her a name, so that she’s not a lost soul. Whatever happens from there, I can’t tell you. But it’s a start. You told me yourself, Simon. This isn’t about revenge. I’m giving you back your own advice’. Simon laughed. ‘I can’t refuse that, can I?’ He stood up and began to walk back towards the shore. ‘By the way, Morag, has anyone told you you’ve got a really nice bum?’ Morag stared after him for a moment, and then ran after him. ‘I’m going to give you a good slapping for that!’ The people around them on the pier, laughed and applauded. They arrived down on the beach, out of breath, and red in the face. Only Annie, Sister Teresa, Sniffer and Adrian were there. ‘Sit down, both of you’. said Sister Teresa. ‘I have something to say’. They sat down silently. Annie looked appealingly across at Simon, her face desperate and worried. Simon smiled at her. She smiled back, realising that he was no longer away. He had come back. ‘The others have gone, to think about what you and Annie found out last night’. She sighed. ‘Oh, I wish, sometimes, that the pair of you would not be so obstinate!’ ‘Why should we?’ replied Simon defiantly. ‘What’s going on?’ demanded Morag. ‘Have they been doing something unlawful, that I should know about?’ She looked at both of them accusingly. ‘My dear, said Sister Teresa, sadly. ‘Yes, but no. They have touched the face of evil’. Morag looked around. ‘I don’t understand’. she said weakly. ‘You will. When Annie and Simon tell you. But not now’. Sister Teresa looked hard at Simon, but she spoke softly. ‘Simon, I am going to say this to give you comfort. I know how much grief and sadness there is in you, as a result of your actions last night. Think back. When your sister cried out, you broke that terrible mirror. Am I right?’ ‘Yes’. said Simon slowly. ‘I thought Annie was in danger’. ‘When you broke that mirror, what happened? Tell me!’ ‘It broke, and there was such a sweet smell. It was wonderful! It was fragrant!’ It smelt like, like, lily of the valley, those little flowers that come out in the spring!’ Sister Teresa sat back and sighed. ‘You released her soul, as I would call it, or her spirit, if you prefer. That was the scent of that poor little girl. She is free now. You have done a wonderful thing Simon. You might not know it, but you have’. She buried her head in her large brown hands. ‘I don’t get it!’ squawked Adrian. ‘What’s this about spirits and things?’ ‘Have I got this right? You broke into a house last night and released a soul or spirit, or something? That’s breaking the law!’ Annie stared at Morag. ‘Go on then. Arrest us. If you dare!’ Morag stared back at Annie. ‘You know I wouldn’t’. Sniffer raised his head and broke the silence. ‘Don’t be daft, Morag. You can’t prove it. Annie and Simon did what was right’. He paused to take another sip from his bowl. ‘Sister Teresa’ s right. This is far more important than breaking laws. Your mother would know that!’ That stung badly. Morag got up, her anger boiling over. ‘Don’t you think my mother knew what she was doing! How dare you!’ ‘Yes she did, and so should you! This is more than trespassing! Ask Sister Teresa!’ ‘Be quiet, all of you!’ Sister Teresa folded her large, hooded arms in front of her. ‘The Brotherhood, and Sisterhood of the Hand is no longer just a society of amateur detectives. It is a group of people, of all species’, looking at Adrian and Sniffer, ‘who are. whether they like it or not, fighting against evil forces, inside a whirling universe, that they, at present, neither know or understand. I do not understand it myself, though Annie and Simon might have some concept of it. But it is crucial, for all our sakes, that we stand by each other, and share the same principles. We may have to break laws to do so’, looking directly at Morag. ‘But we have gone beyond all normal things. We have to fight an evil, in order to do good. We are not judges: we have to do what we feel is right. That is all I can say. The rest I leave to you’. They were all silent. Then Sniffer spoke. ‘Sorry to speak out of turn with you, Morag. We all know you’re a good lass. You’ve got problems of your own to sort out. We know that. But, shall I tell you a joke, that I knew when I was in the French Foreign Legion? They all groaned. ‘I’m going to tell you anyway. My mate, he said, “whenever you have enemies, always occupy the high ground’. ‘Go on,’ sighed Annie, ‘Why do you have to occupy the high ground?’ ‘Because you’re better than they are, and….’ he looked at Adrian. ‘You should know this better than anybody’. ‘Course I do! Because it means you can piss on your enemy from a great height!’ he squawked in delight. They all groaned again. ‘Anyway, I thought it was funny. Right I’m off to find Pat in the pub. You coming, Adrian?’ ‘You bet! Plenty of nosh around!’ The four of them remained sitting around the table. Annie came round and sat next to Simon. She squeezed his hand gently. ‘I thought I’d lost you’. she said very softly, so that no-one else could hear. ‘Please don’t go away from me again. I need you. You’re my brother. I love you’. ‘I won’t’. Simon squeezed her hand back. ‘I promise’. ‘We must all depart, like the others. I have visits to make, to my old people. They need talk and conversation. Farewell, until next time’. Sister Teresa beamed at them and then strode off, her heels clattering among the pebbles. ‘Come on back to our house for supper, Morag. I’m cooking, but I promise you it will be good!’ ‘I don’t know’. But Morag thought of her lonely little flat. ‘Please come, Morag. We both want you to. You can meet our parents, and have a good supper. Simon is really good at cooking, finally! We can tell you everything about what happened last night’. ‘Thank you, I would like to come. I suppose that means I have to give you a lift, doesn’t it?’ ‘No pain, no gain. Please come, Morag’. Simon said sincerely. They drove up the Ditchling Road, talking happily. Then Simon shouted. ‘Morag! Stop!’ She pulled in quickly. Simon and Annie got out and stared at a large semi-detached house on the same side of the road. ‘What is it?’ she asked in bewilderment. The house gleamed with bright paint. The flower-boxes were filled with geraniums. The steps were newly repaired. Inside they could hear a child laughing. A young woman came across to close the curtains across the front window. She waved at them before she did. There was a garage at the side where a car sat, complacent as a cat. It was a happy, prosperous dwelling, a young family warm and secure inside it. ‘Was that the house?’ Morag asked. She was looking forward to eating and being warm inside a house herself. ‘It was’. Morag couldn’t see the expression on Simon’s face. ‘It wasn’t like that. The house we went in has gone. I don’t know where. And that mirror. I smashed it, because I could’nt bear it’. Why was that, Simon?’ Annie asked quietly. ‘It wasn’t just because of me, was it?’ Simon didn’t answer, immediately. Finally, he said. ‘The mirror of our life does not reflect us. It reflects what we might become’. ‘Simon, is that a quotation?’ ‘No. Perhaps. It might be. It was just something that I felt. Let’s go and have supper’.

Frank Jackson. (06//08/10) – word count - 9789

The house that Annie and Simon visited that night.

|

BACK