|

The return of the Alchemist

Dramatis personae

The Brotherhood of the Hand, a small society, dedicated to mystery, consists of four elderly men, in equally elderly grey suits, who correspond to the fingers of the human hand. Simon and Annie, brother and sister, have become members of the Brotherhood, as have their friends, Indira, Pei-Ying and Mariko. There is also Adrian the seagull and Sniffer the dog, the eyes and nose of the Brotherhood. Sister Teresa a dedicated nun with strange powers, and Pat, an Irish academic. A new member is Morag, half-policewoman, half-faery. Together they fight a war against their arch-enemy, Doctor Wrist, and his associates. The scene now, is not the seaside city of Brighton, but the Mediterranean island of Malta.

“Lying trapped, this message is written by Francesco of Seville, a humble soldier of arms in the service of the Knights of Saint John. I pen this message from the grave, in which I shall soon reside, in this barren rock of Malta, my last home and resting-place. My comrades are too weak and injured to lift the stone under which my legs are crushed. They have gone and I shed my tears, but my sword is by my side, and I trust I will give a good account of myself, when the Turks overwhelm us at dawn .We have no hope of succour, though we can see our companions across the water, who have now had to abandon us to our fate. We do not blame them. They cannot do otherwise. Soon the might of our enemy will fall upon them also.

They are ringing the chapel bell! I can hear our enemies shouting in derision, thinking it is our last call for help. It is not. It is our last act of defiance, before they sweep us away. They have burnt and destroyed all the things in the church, which they might desecrate, and now we await our fate. Here I lie, but my faith remains strong to the last. I can hear death over me, flapping his dark monstrous wings. But they will not prevail. I am secure in my faith in my Lord. Let them come!”’

Annie had finished reading her brother’s attempt at describing the last stand of Fort St Elmo, conquered by the soldiers of the Turkish empire, during the siege of Malta in 1565, nearly four hundred years ago. She looked up.

‘Why did you write this, Simon? she asked quietly. They were standing in Fort Saint Elmo, on the end of Valletta, now completely rebuilt, looking over towards Vittoriosia, across the Grand Harbour, crowded with small and large ships of all descriptions, where the last stand of the Knights of Saint John had held out for so long against the great Turkish invasion. The great fort of Saint Angelo lay opposite, its huge limestone-yellow walls both threatening, and secure.

‘I don’t know. I just identify with what the people at that time must have felt. I was talking with Ray, as well, who told me a lot of things about that period in history’.

Ray Cassar, and his wife, Ina, and his daughter, Claire, were friends of their parents. They were Maltese, and had a house at Naxxar, near the old capital of Mdina. Ray knew the history of Malta well, and Simon had listened avidly to him, as they drove back from the airport at Luqa. Simon had been captivated by Ray’s account, together with Ray’s collection of model soldiers, that Simon was equally excited about.

Annie grinned at him. ‘You’re not going to write a history of Malta, are you? I know you. You really like history. If, and possibly when, you go to university, you could do a degree in it’.

‘Perhaps I can. What about you?’

‘I don’t know. Psychology and Sociology?’

‘You’re good at that. But we can’t forget what we came here for’.

Annie’s smile faded. ‘I know’.

Earlier, in fact more than two weeks ago, they had come back, bruised and shaken, from their experience of a world beyond their control. Sister Teresa had brought them home, and explained quietly how it had happened. As a result, their parents had decided that they all badly needed a holiday. They had come with them to Malta, a small island in the middle of the Mediterranean, and the scene of many battles and invasions over the centuries. Both Simon and Annie were tired and miserable, and they both needed to recuperate. They had gradually relaxed, both swimming and snorkelling in the deep rocky seas around the island.

Annie had fallen in love with the sharp vividness of the landscape, its low arid hills, low dry-stone walls, the cacti and the small, slithering wildlife contained in it, the little green geckos, that darted around the small villages, and the enormous churches that stood as centrepieces in the midst of small, baked limestone dwellings, that tumbled, rectangle upon rectangle, around them. It was the little passages and courts, small oases from the heat, that enthralled her. It was a stony, barren island, but with so many Neolithic and Roman ruins, dotted here and there, that she felt that she could literally pick up pieces of history, and hold them in her hands. Ancient peoples had once stood and talked, and lived their lives, in this small island.

The week before, they had sat around their usual table, on the beach in Brighton.

‘I am so glad that you and your’ parents are going to take a well-deserved holiday!’ announced Index Finger, grandly.

‘You certainly deserve it’ added Little Finger.

‘Why?’ asked Annie bluntly.

They were all there, at the beach café where they met in the summer months. The Four Fingers, Adrian the seagull, Sniffer the dog, their friends, Indira, Pei-Ying and Mariko, Pat, the scholar, and Sister Teresa, the large robed nun, who sat quietly beside Annie. It was she who spoke first.

‘Because’, she paused, ‘You might well find out a lot more than we can, about our enemies, Doctor Wrist and his family from hell, and about other things besides’.

‘About what we are doing, and where we might be going?’

‘Of course. Your mother and father have asked you to go to Malta with them, for a purpose. To finally meet Nicolas Flamel, the great philosopher, the man who has achieved immortality. Where else? He is at home there’.

‘Fine! snapped Morag. ‘Don’t mind me! I’m just an accessory’.

She had walked down as silently as she could, and joined the group. She still felt bitter that she seemed to fulfil such a small role in the Brotherhood, and that they almost ignored her.

‘I just want to play my part, that’s all’. she muttered sullenly. “Apart from getting shot by an arrow, and nearly strangled, I don’t seem to have done much’.

‘Do not worry, Morag’ rumbled Sister Teresa, comfortingly. ‘I think your time will soon come. Have no doubt about that’.

Annie squeezed her hand. ‘Honestly, Morag, we’re not excluding you from anything. We all know your strength and courage. We just don’t want to get you into trouble. At least, not at the moment’.

‘I suppose being a copper rather compromises me, doesn’t it?’ replied Morag, bitterly.

‘Not at all, Morag’, Simon reassured her. ‘just think of yourself as our tactical strategic weapon, to be suddenly unleashed on an unsuspecting enemy’.

‘If you say so’. Morag said, resignedly.

‘Believe us, Morag, we need you’. Index Finger spoke sincerely. ‘We will need everybody when the time comes. But not now’.

‘But what do we do in the meantime?’ asked Annie, looking around the table.

‘Nothing’. This was Middle Finger. ‘We take advantage of this breathing space to rest, and put together all the information that we have on the Wrist family. Then we can decide upon a strategy for the future. In the meantime, I suggest we all take a holiday’.

‘No more meetings until Simon and Annie return’. added Little Finger, the shortest and plumpest of the four. ‘Hopefully, they will return with more information’.

‘I declare this meeting closed, and we can reconvene in two weeks time’.

‘We’ll send you all a postcard’. Simon grinned.

As the meeting broke up, amidst a chorus of farewells, Adrian sidled up to Morag. ‘You’re a bit of a keen copper, aren’t you? Bet you just need an outlet for that nasty temper of yours. Almost as bad as Annie’s’.

‘Cut it out, Adrian!’ Annie snapped.

Morag fixed him with an icy glare. ‘Yes, and I’m saving it for foul-mouthed carrion birds like you’.

Sniffer chuckled into his bowl of Guiness.

Adrian spread his wings, with an indignant squawk, and soared off into the bright blue sky.

Sniffer looked up at Morag. ‘Don’t mind him, lass. He’s just winding you up. He’s a bit fed up like the rest of us, as well. And he hasn’t had any grub for at least half an hour’.

‘If he eats any more, they’ll have to register him as a jumbo jet’. remarked Simon maliciously, who had overheard the exchange.

‘Yeah, well. I reckon we could all do with a holiday. Have a good time, you two. See you when you get back’. Sniffer ambled off in the general direction of Pat, and the pub they frequented.

Annie looked at Morag. There were two red spots of anger on her cheeks.

‘Do you two want a lift home?’ she asked tersely.

They drove home in silence, Morag still fuming. As they got out of her car, outside their house, Annie turned around, and leant on the car’s door.

‘Can’t you put in for a holiday, Morag? You deserve one as much as anybody. You’ve taken a lot of punishment lately, You really need a break like everyone else’.

‘I wish’. Morag said gloomily. ‘If I’m lucky I might get Christmas off, but I’m not holding my breath. They always give preference to married cops with families. Spinsters like me don’t get a chance. Anyway, have a good time. Send me a postcard’. She put the car into gear and drove off. Simon and Annie watched as she disappeared down the road.

‘I wish she was coming with us’. Annie said, sadly.

‘So do I. She needs it. Annie, I’m really troubled about her. She doesn’t really know whether she belongs or not’.

‘I know. I can see it in her. She’s confused and insecure. I wish we could do more to help her. She means a lot to both of us’.

‘We’d better finish packing’.

They turned and went back into the house.

The main street of Valletta was crowded with tourists, avidly scouring the shops and stores on each side for Maltese lace, knitwear and glass, all specialities of the island. Simon and Annie didn’t care very much for the tourists, or for the commercialisation of the island, but they did like the colour and character of the buildings they passed, and the general friendliness around them. The sun was hot on their backs, even though it was early September, and late in the afternoon. Annie pointed up at a large building on their right.

‘What’s that, Simon? It looks really Italian to me’.

‘I think it’s an apartment block, with shops, underneath, on the ground floor. It’s a really nice building, isn’t it?’

I love the colour of it. It’s honey-yellow, with pairs of little rounded windows. What’s it made of?’

‘Limestone. It’s quarried here. Almost every building is made from it. It’s quite soft, but it hardens with the sea air’.

‘What are those little enclosed balconies all along it, held up by stone brackets?’

Simon stopped and looked up. ‘They’re a bit like the kind of things that you get in Arab countries. They have screens on them there. It’s so you can look out on the street below, but the people in the street can’t really see you. You’re inside, but you can enjoy the outside as well. I think, in Arab countries, they call them, what is it…..roshan’.

‘I like Malta, even though it’s rocky and stony’. She tucked her arm inside Simon’s and they continued to stroll down towards the main gates, and the huge roundabout outside, where the elderly Maltese yellow buses gathered, to take their passengers around the island.

Simon stopped dead, staring at the tourist information office across the square.

‘I don’t believe it!’

‘What?’ asked a puzzled Annie.

‘Look! Who do you see?’

She looked, and gave a squeal of delight.

‘I can’t believe it either!’

‘Shall we spring a surprise?’

‘Why not?’

They walked purposefully across the square, and stopped behind the slim, dark-haired young woman, who was standing outside the office, reading a brochure, her suitcase beside her.

Simon clapped his hand on her shoulder. ‘I arrest you for being here! You do not have to say anything which might incriminate you, but I…..’

The girl whirled around in fury, her hands whipping up to defend herself. She stopped, stared at them and then laughed in delight.

‘Simon! Annie!’

‘Hello, Morag!’

They hugged each other.

‘Tell us what you’re doing here. Morag’.

They were sitting in the bus, going towards Saint Paul’s Bay, where their parents had rented a large apartment on the seafront. They had just clambered on it in time. Morag’s suitcase was perched precariously in the luggage rack above them, and Simon glanced apprehensively at it from time to time, in case it fell down. The bus was crowded, and the chatter of Maltese and English filled the interior around them.

‘Well, I took your advice and asked my boss, Melrose, if I could take any holiday time. I would never thought he would, but he said “take a week, and be off with you”’. I couldn’t believe it, because we were so short-staffed! But I think he pulled some strings, so I booked a flight here, at short notice. I came in to Luqa airport, this morning, I was just thinking of seeing if I could book a hotel somewhere, when you surprised me. I still need to do that’.

‘No, you don’t’. said Annie quietly.

‘Stay with us. Our apartment’s very big, and it has a spare bedroom’.

Simon looked at Annie, who nodded vigorously.

‘We’d like you to’. she said very quietly.

‘But what about your parents? What will they think?’

‘Morag, I think our parents will be very happy to see you. They know you’re one of us, and I know they like you. That’s settled’.

Annie settled herself back on the seat with her arms folded, a large grin on her face.

Morag looked helplessly at Simon who shrugged. ‘The wise guru has spoken. My pretty sister has made up her mind’.

Annie opened her eyes wide. ‘Simon, you just paid me a compliment! What’s come over you?’

‘I’m just in a good mood. Make the most of it, while it lasts. We’re really glad you’re here, Morag’.

Morag smiled. ‘Come on, tell me. How have you got on with the local talent?’ ‘Really, Morag, what an improper question to ask!’

‘Get lost, Simon. Go on, tell me. have you been snogging, and fondling in back doorways?’

‘None of your business, Morag’. said Annie, loftily.

‘Oh, so you have, then. Good. Any room for another one?’

They all burst out laughing.

“Our two knights of the Order of St John, de Guaras, and Captain de Miranda, sat like two black beetles in the breach, on chairs, too badly wounded to stand, swords by their side. I saw them, by turning my head to look up. It was spear and sword, dagger and pike that day. We fought like furies, though all were wounded. Thank God, I have survived so far. There are so few of us left. There is no-one around me. I still have strength to write this, and I pray to God that the cursed Turks will not find it on my body. This is the last testament of St Elmo. There is no hope. I pray that Christians everywhere will always remember us. We fought to the end. I commend my body to the Lord, and wait for the last battle. We did all we could. We did all we could. Amen”.

Morag looked up from Simon’s view of the great siege of Malta, and asked exactly the same question that Annie had asked a few days earlier. ‘Why did you write this, Simon?’

They were sitting on the balcony of their apartment, that looked out over the dark expanse of St Paul’s Bay, Simon didn’t answer at first, but got up and leant on the rail, gazing out over the vivid blue Mediterranean sea.

‘ I suppose that I identify with that battle. The savagery, the despair, and just the sheer bravery of it. To fight right to the end, knowing that everything was lost, but just simply not giving up, ever. It doesn’t matter that they were Turks and Christians. They were all human beings. But just to fight on like that, whatever faith you had. I find it just, I don’t know, almost unbelievable, and terribly, terribly sad’.

Morag looked around, biting her lip. Annie was sitting, hunched in a corner of a chair on the other side of the balcony. She was totally silent. Morag couldn’t bear it any longer.

‘Simon, please forgive me, and don’t answer if you don’t want to. But tell me, is it because of the battle that you fought a while ago? Before I was around?’

She waited in fear for Simon to explode. But he didn’t. He was quiet for a few seconds. Annie remained motionless.

‘Oh, damn! I’m sorry! I wish I hadn’t asked! It’s not fair on you! I’ve not even any right to know!’ Morag got up abruptly, feeling desperately embarrassed and furious with herself.

‘Sit down, Morag’. said Annie, quietly.

She sat down, feeling very foolish, but was then suddenly aware that they were both smiling at her.

‘Tell Morag about our battle, Simon. She should know’.

Simon leaned back against the balcony railing. ‘Before you came into the Brotherhood, and Sisterhood, Morag, we had to fight a great battle. We had to stop an invasion, just as they did in Malta, all those years ago. No-one outside the battle will know anything about it, because it was fought in another dimension. But it was savage and bloody, and it hung in the balance, until we got reinforcements. We were fighting daemons, and we eventually defeated them. But we lost a lot of our own – faeries, dragons and….our Mr Cuttle’.

‘He didn’t even need to be there. But he did come, and he was killed. A lot of us were badly wounded as well’ Annie whispered.

‘It’s not something that’s easy to talk about. But you’re one of us. We can tell you. That’s why I’m so interested in the great siege here. We can identify with it, even though it was so long ago. Yes, it is connected with our own battle. We can understand it, and feel for the people involved. War is cruel and evil, Morag, but sometimes you have no choice. They didn’t, and we didn’t. That’s why we feel incredibly miserable at times’.

He fell silent.

Morag decided to change the subject. ‘I’ve got a date this evening’, she said, rather smugly.

‘Not with that rather dishy Swedish teacher that you were talking to at the beach this morning, by any chance’, enquired Annie, mischievously.

‘Might be. Anyway, you take care of those young Swedish students of his, which you seem to have done already. I’ll deal with the teachers. See you later’.

‘Remember, Morag, we want a full written report, when you get back’.

Morag stuck her tongue out at him. ‘Only if I’m lucky’.

After she had gone, they remained silent, staring out at the dark sea. Then Annie stirred. ‘I’m going down to the sea and paddle my feet in the water’. She looked across at Simon, almost timidly. ‘Will you come with me? I think there are things to talk about, just you and me’.

‘Yes’, replied Simon, very quietly, ‘We do need to talk’. He stood up. ‘Dad’s going to tell us tonight, whether we’re going to meet Nicolas Flamel’.

‘He’ll find us’.

They walked quietly down the small road to the shore, where they had found a low rocky shelf to sit on. They paddled their bare feet in the cold Mediterranean water. The sea gurgled and lapped around them, a small occasional splash sounding the presence of some small marine creature. They listened to the softness of the water moving against the stone beneath them. ‘Why do you hate Ragimund, Annie?’

Annie sat bolt upright, startled. She had not expected such an abrupt question. Ragimund, as a faery queen, had fought with them in the battle. She was fierce and dark-eyed, who, at first, had seemed vicious and brutal. But she and Simon had developed a relationship, which Annie knew was a strong one. She had often taunted her brother about it. But she had not realised just what it meant to him, until this moment.

‘I don’t hate her Simon! It’s just that I….I’m trying to find the right words to express what I feel!. She took a deep breath.

‘It’s just that I don’t understand, how you and Ragimund have come to care about each other so much. She was cruel to you in the beginning. I don’t understand it because you’ve seen so little of each other. I know she’s very beautiful, and I’m sure that she’s not as nasty as when we first met her, but I just can’t understand why you’ve fallen in love with her! She’s a faery!’

‘That doesn’t mean she’s not unattainable. Have you ever heard of love from afar, Annie? That’s what I feel about Ragimund. But there’s more you want to tell me, Annie, isn’t there? Please, Annie, I really do want to know about what you’ve not been telling me. Now is the best time’.

Annie looked down at the deep, swirling water for what seemed a long time.

‘I’m afraid of her, Simon’. ‘Why?’

Annie clasped her hands together. ‘I’m afraid that one day she’ll take you away from me, and we might never be brother and sister again. I can’t help it. I’m not jealous of Ragimund, please believe me, but I’m frightened that we’ll never be the same. That’s what’s been on my mind all this time’.

Simon spoke very quietly, so that she had to lean forward to hear him.

‘What if you fall in love with someone, Annie, in the future? Does that mean they’ll take you away from me?’

‘I hope not’. Annie said sincerely.

‘Then why should you think that Ragimund will take me away from you? You’re my sister, Annie. I love you. It doesn’t mean that if either of us fall in love with someone else, we have to give that up! I don’t believe that the bond between us will ever be broken. It can’t be. That’s our strength. That will always be there. Ragimund has sisters too, who she loves. Do you think she would ever walk away from them, even if she and I fall in love with each other? I wouldn’t expect her to, and nor would she. Try looking at it in another way. If people fell in love with somebody else, doesn’t it mean that that bond we have is made stronger as well, by the happiness of those that share that bond?

Annie sat staring into the deep waters below. She didn’t say anything.

After several minutes, she spoke. ‘Simon, I really think you’ve become a faery’.

Simon got up. ‘I knew it was a mistake, telling you this’.

‘No!’ She pulled his arm fiercely, forcing him to sit down again. ‘What I mean is, I totally agree with you!’

She stared hard at his face. ‘What I was going to say is, that you’ve matured so much, more than I have. You see things I can’t see. Simon, you’ve just lifted a terrible burden from me. That’s what I was worried about. And you saw that!’ She pulled his arm again. ‘ I promise you, sincerely, that I will never tease you about Ragimund, and that I will never be rude about her again. I understand now, Simon, I really do. Thank you. I love you very much’, She gave him her radiant smile, that he could see even in the dark. ‘At the risk of being soppy, will you give me a big hug?’

Simon obeyed, still bewildered, and not quite knowing what he had said to make Annie so happy.

‘Hi. I thought I might find you down here’. said a mournful voice behind them.

They looked up. Morag stood behind them, looking rather morose.

‘How did your date go, Morag?’ Simon called.

But Morag was looking around. She had sensed terrible tension in the air. Her faery instincts told her that something momentous had happened around Simon and Annie.

‘Have you two had a quarrel?’ she asked quietly.

To her surprise, Annie and Simon both burst out laughing.

‘Right, that’s it! If you two want to make fun of me, go ahead! I’m going to bed!’ ‘Morag, come back here! We’re not making fun of you at all!’

She turned back, reluctantly, and paused again. She could still sense the acridity of tension, but it was rapidly disappearing. Something had been and gone here, she decided. Simon and Annie moved up so that she could sit down on the ledge between them.

‘My shoes are killing me!’ She pulled off her high-heeled sandals and dipped her feet into the water. ‘Oh, that’s better!’ ‘So what happened, Morag?’

‘Well it was a really nice romantic evening. Nice food, plenty of wine, soft candles, until,’ she paused. ‘Until what, Morag?’

‘Until he started telling me about his pregnant wife back home in Malmo’.

Simon quickly suppressed a giggle. ‘How awful for you, Morag’. he said solemnly.

Morag glared at him suspiciously.

‘Well, at least I got a nice meal out of it. Come on, what have you two been talking about?’

Annie didn’t reply. She had turned to look at where a dark figure was climbing down towards them.

‘Over here, Dad’. she called.

Their father came and squatted down beside them. ‘I’ve got some news at last’. he said quietly. ‘Nicolas Flamel would like you to come and see him tomorrow evening at ten o’clock. He has an apartment in Mdina, the old capital of Malta. He said he would very much like to meet you’.

Simon and Annie remained silent. Morag looked around at them both.

‘I’m coming with you’. she said flatly.

‘Morag, I’m not sure,,,’

Their father held up his hand. ‘It’s all right. Morag is invited too’.

‘I am?’

‘Yes, definitely. I’ll drive you down to the main gates shortly before the meeting. Because the streets are so small, cars aren’t allowed into Mdina itself. I can come and pick you up when you’ve finished. By the way, Morag, how was your evening?’

Morag groaned. ‘Please don’t ask’.

‘That bad, was it? Oh, well, I’ll see you all at breakfast then’. He got up and went back up to their apartment.

‘You can’t complain any more about being excluded now, Morag, can you?’ Simon laughed.

‘I suppose not’. Morag said thoughtfully. ‘Tell me, what do we actually want from this meeting?’

‘What does Nicolas Flamel want from it?’ suggested Simon. ‘He must have some purpose’.

Annie shook her head, and sighed. ‘I don’t know. But apart from meeting an immortal philosopher and alchemist, we’ll just have to wait and see’.

They sat in subdued silence, the sea still murmuring quietly around them.

************

“I, Don Mesquita governor of Mdina, the Citta Notabile, hereby give thanks to God for our deliverance from the infidel in this year of our Lord.. I have ordered a service of celebration to take place in our blessed cathedral, and now note down all that has transpired y the actions of our citadel.

On hearing of the Turk’s intention to beleaguer our small fortress, my intentions were simple. Having so few men at my disposal, I ordered those Maltese sheltering within our walls to dress as our foot-soldiers, and commanded them to man our ramparts on the side from where the Turk would attack. I caused what cannon we had to be run up to the walls, and fired what little shot and powder we possessed, towards the enemy. They paused, thinking that we were as strong and formidable a garrison as they have otherwise encountered. We waited to see if our trick worked.

Behold! The Turk became afraid of the losses he might endure if he was to attempt so strong a position as ours! His siege guns began to withdraw, as indeed his troops also. He is now at a loss. Our Brethren in Birku and Senglea still hold. The gunfire from the battle there can be heard throughout our city. Pray God that reinforcements will arrive soon. Otherwise, all may still be lost”.

‘Is there a moral to this story, Simon?’ asked Annie, quietly. They were sitting on a bench, outside one of the two narrow gates that led into Mdina.

‘I suppose it means don’t be taken in by false appearances’. Simon sighed. ‘But it did happen. All Mdina had, were a lot of Maltese refugees, but they still frightened off the Turks’.

‘So perhaps we shouldn’t take this Nicolas Flamel at face value then?’ volunteered Morag.

‘I’m not saying that. I just mean that not everything should be taken as it seems. But that doesn’t mean the trick wasn’t right. The governor actually saved a lot of his people, by means other than just fighting the enemy. That’s another way of looking at it’.

‘That’s true’. agreed Annie. She stared at the narrow gateway that led into the small, darkened streets of the mediaeval town. Their father had dropped them at the entrance, and now they had to walk through Mdina to find Nicolas Flamel’s house. ‘We’d better go. It’ll soon be time’.

They walked through the gateway, all wearing jeans and dark sweaters against the chill of the evening air. The dusk and quiet swallowed them.

They walked on through the narrow quiet streets. There were no cars, only the distant hum and tone of people’s conversation as they passed by. They turned left, and then right, past the Chapels of Saint Nicholas and Saint Peter, onto the main, central Villegaignon Street. The quiet and peace of these little avenues, narrow and slightly crooked, was overwhelming to their ears, so used to traffic noise. They passed by even smaller and emptier streets on each side, only encountering others in small groups or couples. Not even conversation could be heard now.

Morag gazed around her in awe.

‘It really feels like a mediaeval town! So enclosed and quiet! I keep expecting a patrol of soldiers in armour any minute!’

It was true. They were all conscious of being enclosed by the high stone walls of palazzos and churches, through which the streets, sometimes no more than large alleyways meandered, like streams finding a path. Small shrines, with the upright figure of a saint enclosed within them, marked the sharp corners above their heads .The lighting of the street-lamps was dim, and far between. They were moving towards a small cluster of narrow streets at the far end of Mdina, just beyond Carmel Street. It was here that Nicolas Flamel lived.

At last, they found the doorway they were looking for. It was open, leading into a small stone-paved corridor. At the end was a small flight of steps, that stopped at a large panelled door, slightly ajar. They went up the stairs and paused. Simon tapped gently on it. The door swung open. They looked at each other, and then walked in.

The room was large and square with a high ceiling. Two French windows opened out onto a long balcony on the right, looking out over the dark plain of the countryside. Directly in front of them were three tall leather chairs, upholstered with small brass rivets, their backs towards them. They were grouped around a small table, beyond which a small stone fireplace contained a brightly glowing gas fire, that occasionally sputtered. Two other high-backed chairs, mounted on pedestals, stood at each side of the others. The walls were filled with shelves of leather-bound books, their golden titles on each spine glinting in the light from the fire. Two shaded electric light brackets, each side of the fireplace, provided a dim and suffused light to the interior.

They stood and stared, uncertain of what to expect. Then the right-hand chair slowly swivelled around. The figure in it stirred suddenly.

‘Good evening! I was expecting you. I am Nicolas Flamel’.

The voice was warm, almost musical, and deep, as if the speaker spoke his words with great care. Nicolas Flamel was not what they had thought. Not a tall, ascetic, gaunt individual, but a small, rather rotund man, whose hair had thinned to reveal a shining pate, but who still possessed a full grey beard, a slightly hooked nose, and two very sharp black eyes beneath bushy grey eyebrows, that looked at them penetratingly. Any resemblance to Doctor Wrist instantly evaporated.

‘Pray, let me introduce you to my dear wife, Peronelle’. indicating with a hand towards the other chair. It turned around. A small plump woman, with a mischievous round face sat there, her needlepoint sewing in her lap. Her grey hair was neatly pinned back in a bun.

‘Greetings to you! We are not exactly as you expected us to be, are we? she chuckled. Her voice was equally warm, but slightly higher than her husband’s. ‘This is a good meeting, tonight, is it not, Nicolas?’

Annie, still open-mouthed, suddenly remembered her manners. ‘We…we must introduce ourselves. I’m…’

‘Annie! I know’. said Nicolas Flamel, cheerfully. ‘This is your brother, Simon, and this, if I am not mistaken, is your new sister, Morag, daughter of Moran’. You are all, I take it members of the Brotherhood, and Sisterhood, of the Hand. It is a great pleasure to meet you at last’.

‘Ah, Morag! Well, I never! You look so much like your mother’. Husband dear, would you like to pour the tea for our guests’

‘Of course, dear’.

He got up to pour the tea very precisely from a tall samovar-like teapot into the small china cups and saucers arranged on the small table in front of the fireplace. Annie glanced at Morag, and was suddenly shocked. Morag’s face was crimson with fury, and her body was tensed as if about to spring out of her chair. She shot a warning look at Simon, on the other side. He nodded. He had seen it too, and reached out a hand towards Morag. Too late.

She sat upright in her chair. ‘Don’t you think this little charade has gone on far enough! All this cosiness! You expect us to believe you’re great immortals, with the elixir of life! Come off it! You’re just two old people who are having a big joke at our expense! Come on, who are you? Sid and Gladys from Blackpool, probably!’

Nicolas Flamel paused in the act of pouring the tea. ‘Oh dear. time for my little trick’.

He put down the teapot, held his left hand outstretched, palm outwards, and said very quietly, ‘Vene’.

Both the talismans that Annie and Morag flew off their fingers. They found themselves looking at Nicolas Flamel’s left hand, where both their talismans now embraced his third and fourth fingers, next to each other, A similar ring, slightly larger, encircled his index finger. All three rings were glowing brightly, pulsing with white flashes of light that highlighted the shadows of the room.

Nicolas Flamel put down the teapot, and sat down again in his chair. He held up his left hand, with the talismans still glowing, and looked at them rather absently.

‘Well, my children, you have come home to me. Now back to where your rightful place is. Vene!’

Morag and Annie, still half-standing, looked down at their hands. The talismans were back, still glowing brightly. They sat down abruptly, amazed. Only Simon remained standing. He looked at Flamel and Peronelle. They smiled back. Simon suddenly believed them, or rather he felt he believed them.

‘Doctor Flamel, Mrs Peronelle. These are your creations aren’t they? You created them when, or soon after, you became immortal. You made them. But why?’

‘ I will tell you, Simon, and the others too. But only after we have had tea! Peronelle, my dear, will you look after our good faery there? I fear she is somewhat distressed’.

Morag was sitting, quietly sobbing, feeling mortified and ashamed. Annie was standing by her, her arms comfortingly around her shoulders. Peronelle pulled out a small lacy Maltese hankerchief, and waddled across to her. ‘Good for you, my dear. You were right to challenge us, Your mother would be proud of you. Pull your chair over to mine, when you are ready, so we can talk’.

For several minutes, nobody talked. They drank tea and ate what proved to be rather delicious English Eccles cakes. Then Nicolas Flamel looked around. ‘We must talk’. he said, abruptly. ‘This is what you came for, and quite rightly. But first, let me tell you more about the talismans’.

He stared into the glowing gas fire, with its artificial coals. He spoke without looking at them.

‘I created the talismans soon after we became immortal. I wanted to build some things, some elements that I could throw out into the world, that would protect, and heal, and at the same time offer a far-flung link between those that they would gravitate towards. The talismans I created are protectors. They have the power to distinguish between good and evil. They come to those that they trust, and bring them together as agents of communication. My purpose was to sow seeds of harmony, to enable those who received them to use them for beneficial purposes, for the good of humanity. And, ideally, to provide with knowledge, those individuals who possessed them. That is why I know all about you. They report back to me, you see’. ‘So they’re spies!’

‘Not in the way you mean’. replied Nicolas Flamel, still staring into the fire. ‘They tell me who is worthy of bearing them. But I have lost touch with many of them. That is why I am so happy to see two of my creatures together in this one room. It has not happened for a very long time’

‘We know of a third one’. Annie said quietly. ‘It belongs to Jezuban, a faery, who we rescued. I’m not sure whether she really knows what it is’.

‘Jezuban! So the faeries possess another one also! That is indeed good news, husband!’ exclaimed Peronelle, her needlepoint forgotten on her lap.

‘It is indeed. And you are faery, are you not, Morag?’ Nicolas Flamel turned and looked at her steadily. ‘Did your mother give you the talisman?’

‘Yes, she did. She never explained why. She just said that you must look after it for me. She said that I would know when the time comes’.

‘She was wise. She loved you very much, Morag, and she trusted you. You must never forget that. We knew her well. Her judgement was always sound. Don’t be sad, young woman. You are in good company’.

Peronelle said this with a chuckle, and a sharp glance at Annie and Simon.

Morag sat, with her head bowed, clutching Peronelle’s hankerchief in her right hand. The talisman was glowing gently, as if in sympathy. She looked up.

‘I’m sorry’. she said quietly. ‘It’s just that, that I don’t know how to understand, or take all this in. I’m just not used to it. I know Simon and Annie are, but I’m frightened’.

‘Of what, dear?’ asked Peronelle, gently.

‘Of what I don’t know’.

Simon had been gazing intently at Morag, but now he decided to interrupt. ‘Doctor Flamel, how many talismans did you create?’

Nicolas Flamel turned his chair around on its pedestal, so that he could look at Simon.

‘I really don’t know’. he admitted, frankly. ‘A large number, but I cannot remember’. ‘So there are more?’

Yes, but some of them I have not heard from, for some time. But there is something else that you should all know’.

He paused. ‘Do you know why I used the emblem of the hand? No? Let me explain’.

‘You must realise that the hand is one of the most flexible and pictorial ways of representing truths. The talismans have an outstretched hand, like so’. He held up his own hand, palm forwards, the fingers outstretched.

‘This is the gesture of peace, of innocence. It shows that you do not wish, or bear harm to anybody. That is the signature of the Brotherhood, and Sisterhood of the Hand, as you know it. But the hand has other qualities. It can be used to define mathematics, that is. it can count. It can be used for astrology, for telling the fortunes according to the heavens. It can symbolise the number of saints in a religious faith, and above all, it can be used as a universal system of communication, between peoples who have no common language. It can also be used to provide conversation between those who cannot speak, or who are deaf, and those who can. The human hand is a wonderful thing. It can hold tools, it can work materials, and it can paint pictures, or finger a keyboard to make marvellous music’.

They were all quiet for a moment.

‘I often wondered’. Annie said, finally. ‘It just seemed just a peaceful symbol to me. That’s always how I’ve thought of it, whenever I’ve looked down at the talisman on my finger’.

Simon leaned forward, and said abruptly, ‘Doctor Flamel, how is it that you and your wife have become immortal?’

Nicolas Flamel leant back in his chair, clasping his hands on his lap. Peronelle sighed deeply.

‘A good question. I wish I knew!’ he chuckled. Peronelle giggled to herself. ‘Quite by accident, I assure you. All the signs of the universe were in alignment, the conditions were correct, everything seemed in order. So it happened. Peronelle was with me, and we held hands together’.

‘Then what happened?’ asked Annie excitedly.

Nicolas Flamel leant back in his chair even further and laughed out loud, a deep rich sound.

‘Nothing!’ he cried. ‘Absolutely nothing!. We stood there, feeling rather vexed, and then we retired to bed together, feeling somewhat annoyed, I must say’. ‘So that was it? No great flash of lightning, or anything?’

‘Not at all. We only realised in the days and weeks that followed’.

‘You see, my dear’, said Peronelle, gently, putting down her needlepoint again, ‘We stopped growing’.

‘Our hair, our nails, our teeth, just remained as they were on that night. They have not changed ever since. A year later, we looked at each other. It was then that we realised. In our former time, people age quickly. Most do not , did not, live beyond fifty. At the time of our immortality I was aged sixty-five, my wife, Peronelle, only fifty-two years old. We have remained thus throughout the centuries. You see us now as we were then, although, I have to confess, in rather more contemporary clothes and costume’.

‘A great improvement, too’. remarked Peronelle, taking up her needlepoint again.

‘Can I ask you something? said Annie quietly. “I know it’s a stupid question, but’, she hesitated, ‘What is it like to be immortal?’

The question hung like a heavy drop of water, poised in the space above the small group. Annie desperately wished she hadn’t asked.

‘Nicolas, I think you should answer the young lady’.

Nicolas Flamel turned to look at the glowing gas fire again. ‘Immortality is not a blessing , but a curse. To see those who you know and love, age and die before your eyes, is a terrible thing. To know that you will outlive them and their children, and the children’s children, is a dreadful burden to bear. In many ways, it is almost a punishment for achieving what perhaps should not be achieved. All one can do is to preserve the goodness and kindness that one has within oneself, to try to pass on to others’.

He stopped. Peronelle looked at him fondly, and took up the story.

‘We had to disguise our own deaths, with funeral services. We caused a tomb to be erected for Nicolas and I, but we took care to disappear shortly before. You remember, Nicolas, my love, how we visited your own tomb over two hundred years later, and how amused you were?’

Nicolas laughed, and slapped his knee. ‘Of course I do! I was so tempted to say to those gawpers, here I am! But, of course, I couldn’t. Instead we have become nomads in this world, living here, living there, in many different countries, forever moving on after a number of years, lest we invite suspicion for not aging like the rest. That is the saddest part of our existence’.

‘You remember, Nicolas? How we had to pretend to have died in a shipwreck? Once in a volcanic eruption, and then again eaten by crocodiles.! We certainly had to be very imaginative! But I rather enjoyed that part. Disguising one’s own death can be such fun!’ She giggled again, happily, at the memories.

‘ I am now six hundred and twenty years old. I must say I prefer the twenty to the six hundred!’ Then Nicolas Flamel continued, in a sober voice.

‘We have witnessed so many wars and conflicts in our years. But we have been but observers, powerless to deflect or change the appalling things that have happened, in this world of ours. I wish we could. Instead, we carry the great weight of grief and sorrow wherever we go. We do not travel lightly. We drag the dead mass of might have been, and what they should be, in our wake’.

But how do you live? And why Malta? asked Simon, anxious to break the atmosphere of melancholy that had settled upon them.

It worked. Both Nicolas and Peronelle burst out laughing. ‘That is an easy question to answer. We simply buy properties, wherever we go, and sell them at a profit. Then we buy another, and another, just for ourselves you understand, and we invest our income, so that we can live as a comfortable retired husband and wife, wherever we place our roots’.

Morag found her voice. She had been sitting quietly, trying to take in what had been said. ‘So you didn’t turn base metals into gold?’

The elderly couple laughed even more loudly, Nicolas wiping his eyes in mirth. ‘Heavens, no! That is just a myth, that fools believed in! Fool’s gold!’

Nicolas laughed again, and wiped his eyes with the back of his hand. ‘But your second question, why Malta? The answer is that we feel at home in this place. Where you are staying, is the place that Saint Paul was reputed to have come ashore, and converted the people of this island to Christianity. The people here say that they are the first Christians. But let me ask you a question, Simon. Why are you writing about the great Siege of Malta?’

‘Because I admired the courage contained in it. I suppose, also’, Simon spoke quietly and slowly. ‘it seems to be related to what we’ve done. Annie and myself, and Morag, too’.

‘Now is the time to tell me further about your adventures. I must confess to some curiosity’.

Morag stood up. ‘I must go, I have no part in this, really’.

Peronelle leant over and patted the seat behind Morag. ‘Sit down, dear. Now. You should hear this. Nicolas, I will tell their mother and father to fetch them tomorrow morning. Our night will last a long time. They will stay here tonight’. She got up from her chair sharply, and flourished a mobile phone. ‘I will ring them now. Please proceed. I will be back shortly’. She swept past and into the corridor outside, where they could still hear her muffled voice speaking.

‘Please commence’. suggested Nicolas, and sat back in his chair, expectantly.

For the next two hours, Simon and Annie related their story, hesitantly at first, and then more confidently, as they began to piece together everything that had happened since they had joined the Brotherhood of the Hand. They corrected each other over certain issues: at other times they spoke to each other, describing their feelings and emotions at crucial parts of their journey. There were points when both brother and sister seemed as if they would break down, particularly at desperate moments. Yet it did seem as if it was a catharsis, a way of coming to terms with their own loss and grief. Nicolas and Peronelle listened quietly, only interrupting now and then, to clarify, or understand things that were uncertain or confused.

Morag sat, spellbound, hanging on to their every word. She had never heard them talk about their experiences so freely and movingly. She began to understand why they had avoided talking in detail to her about what had happened. She had gleaned a certain sense of what had happened before she had joined them, but she had never realised the extent of their pain and sorrow before. She listened intently, every so often irritably wiping a tear from her eyes. She understood now, Annie’s occasional bouts of deep sadness, and Simon’s interest in the great Siege of Malta. It was their way of trying to come to terms with their loss of childhood, and their struggle to make sense of what had happened to them.

At length, they finished. Nicolas sat gazing into the fire. Peronelle absently picked up her needlepoint again, that had lain in her lap throughout the narrative. Simon and Annie looked exhausted, their eyelids beginning to droop. Simon stared ahead of him. Annie sat clasping, and unclasping her hands in her lap.

‘I’m very happy to have been able to tell you all this’. Annie said quietly. She looked across at Simon. ‘I think we both are’.

Simon raised his head. ‘Yes it is. We’ve never talked about anything in such detail before, not even to each other. It’s given us patterns, ideas, things that we hadn’t recognised. But it raises some other very important questions, which we still need to ask you’. ‘I see’, said Nicolas, absently. ‘Such as?’‘Are there such things as different dimensions and entrances to them?’

‘You should also say exits as well’. Nicolas replied gravely. ‘They are as important as entries. Yes, there are. They shift and move, as you have experienced for yourselves. There is no map, no formal diagram. They come and go as they occur. A few are permanent and well-established, such as those of the faeries’, glancing at Morag, ‘and the dragons. But others are transient, fleeting, here and gone. That is all I can tell you’.

‘How can we track down Doctor Wrist and his family?’ Annie asked sharply.

‘He and his family are an abomination! Nicolas spoke with a sudden passion.’They seek to become magi, for power and influence! Let them come to you, because they are uncertain, and therefore, fearful of you. They will come to you, from wherever dark hole they are hiding!’

‘Defence, not attack. How many times have we heard that before?’ groaned Simon.

‘It is the only way. You will not find your way through the universe’. ‘What is the universe?’

It was Morag, who had blurted out the question even before she realised it. She blushed and looked away from Simon and Annie, who were staring at her, open-mouthed. Nicolas Flamel sighed, and sat upright in his chair.

‘How many times have I been asked that question? My answer has always been the same. I do not know. That is enough’. He said this sharply, but then leant back in the chair with an air of resignation. ‘It is better that, as the very last question, you should ask, what now?’

‘What now?’ asked Simon, rather uncertainly.

‘Ask your questions of the dead!

They looked stunned.

‘I mean this. If you want to find other answers, then you must seek them out from those that no longer live’. Nicolas hesitated. ‘If this is what you wish, I will send you a guide in due course’. He looked across at Peronelle, who nodded slightly. ‘You will know him, when you see him. I think that is enough for this night, my dear’.

‘These young people are drooping like wilted flowers! You will stay for what remains of the night. Annie, Morag, you will sleep in our spare bedroom. There are two beds there. Simon , there is a very comfortable couch in the small bedroom to the left. Go to sleep now! Nicolas and I still have much to discuss’.

Too weary to argue, they got up and moved from the door. Nicolas called after them. ‘We will not be here in the morning, my friends. We have other places to be. Sleep well, and….our blessings upon you’.

As Annie passed through the door, she turned and looked back. She saw two elderly plump figures, one dressed in a brown tweed suit and waistcoat, slightly shabby and crumpled by wear. His round, bearded head was nodding slightly, his face lined with tiredness and age. Opposite, his wife looked at him, her kind, rather dimpled face peering out above a rather shapeless brown woollen dress and sweater. Her face was frowning as she stared worriedly at her husband. Then the door closed, and they were gone from view.

Next morning was bright, sunny and warm, though in the narrow streets and squares of Mdina, the air still felt cold and chill. Nicolas and his wife were, as they had said the evening before, gone. The three of them had risen, still sleepy and tired from the night before, eating toast and drinking coffee in the small kitchen, and shut the front door behind them. As they walked through one of the main squares, they noticed large wooden scaffoldings or frames being busily erected all along the sides of the open space. Some were already standing over twenty feet high, small beams and planks of wood nailed together to form huge timber structures. The sound of hammering and raucous voices filled the morning air.

‘What’s going on?’ asked Morag in amazement. ‘They’re not having public executions, are they?’

Simon looked around. ‘No, they’re preparing for a festa tonight. It’s quite late in the year, so this must be the last one. All those wooden constructions are to mount the fireworks on, for the celebrations’. ‘What are festas?’

‘They’re religious festivals, but in reality, they’re also huge firework displays. Someone told me that they are the best in the world. The Maltese make their own fireworks, you see, and I’m told that they really are the biggest and the greatest. Really spectacular!’

Just then they caught sight of their mother and father waiting by the citadel gate. They waved and caught up with them, amidst a throng of tourists, sightseers and Maltese workmen, carrying tool-bags and long wooden planks across their shoulders.

‘Sorry we’re late, mum’. Annie said, ‘You were right, it was a long night. I hope you weren’t worried’.

‘No, we weren’t. We knew you would be safe with dear Nicolas and Peronelle’. Her mother put her mouth next to Annie’s ear. ‘Did you find the answers you were looking for?’

‘Yes. At least some of them’, Annie whispered.

Her mother lowered her voice even further. ‘Your father and I have decided. From now on we will be watching over you. That will be our first concern’. ‘What about the Watchers?’‘Damn the Watchers! You are our children! You take priority!’

Her mother’s outburst caused the others to look around. Her father glanced briefly at their mother, and nodded. ‘I think we should celebrate our last night in Malta by treating Morag to a festa. Don’t you?’

‘Brilliant! cried Simon. ‘But Morag might be a bit frightened of the loud bangs!’

‘No, I won’t! retorted Morag indignantly, at the same time casting an apprehensive look at the wooden structures inside the gate.

‘Never mind, Morag. When that huge rocket flies up into the sky with you hanging onto it, we’ll always think of you’.

‘And when it explodes, and your mortal remains are scattered across the firmament, we’ll be able to look up and say “there’s Morag”! It’ll be the experience of a lifetime!’

‘I hope it won’t be my last’. muttered Morag, gloomily.

The festa was in full swing when they finally managed to push their way through the crowds of people that thronged the small square outside the cathedral. Everyone jostled and shoved, Tourists in their brightly coloured clothes, Maltese families with small children, even in pushchairs, Morag noted with dismay. Here and there, small figures flitted, setting light to the tight bundles of fireworks mounted above their heads on the wooden frames that towered above them. The noise was indescribable, shouts, yells greetings, applause, as yet another enormous Catherine wheel slowly began to revolve, and then began to whirl around and around, in a violent spinning blaze of red, yellow and purple colours, spitting bright yellow sparks that fell to the ground in and amongst the people milling below. Morag squealed and jumped as a shower of sparks cascaded around her legs.

She felt a hand grasp hers and tug at it. ‘Over here!’ Annie yelled above the sputtering din and press of people. ‘On the cathedral steps! We can watch it better from there!’ Morag allowed herself to be pulled along through a group of young Maltese men, who cheered and wolf-whistled as she was bundled along by Annie. A burly, dark man slapped her jovially on the back, as she squeezed by him, holding a half-empty beer bottle. ‘Good fun, eh!’ he shouted in her ear.

‘Yes, definitely’, muttered Morag weakly, and then found herself on the cathedral steps, where, thankfully, they were out of the crowds below. She looked down at the piazza. It was actually thick with people, all laughing, gesticulating and cheering, as yet another wheel began its motion, slowly at first, and then becoming a whorl of incandescent colours, throwing out gleaming gobbets of light that exploded in the air around it.

She looked up and gasped. Unseen rockets had lifted into the dark blue sky, and then exploded, Great chrysanthemums of gold, purple and silver blossomed high above, one after another, each one replacing the fading flower before. It was extraordinarily beautiful. Morag stared entranced at this enormous bouquet of light that opened up in the heavens, over and over again, replacing gold, silver and green, with red, blue and purple, so bright, that they illuminated the faces of the people below, white oval shapes caught suddenly in the darkness around.

A huge bang shook the citadel. Morag shrieked and sprang to her feet. ‘There’s been an explosion!’

Simon dragged her down again. ‘Morag! That’s just a big bang! They always do that, at the end of each display! Custom, I think!’ She could hardly hear the words he shouted in her ear. She decided to cup her hands over her ears. She had never liked unexpected bangs as a child. She was always fearful, waiting for it to happen, and just as she felt reassured, there would always be a loud bang that made her jump with fright. It had always been a weakness, which she had never lost.

Simon’s face was rapt with excitement. He leant over and shouted in her ear again. ‘Imagine what it must have been like in the great siege! Half-blinded by smoke, cannon blowing your walls away, not knowing what was happening! Day after day, night after night! It must have been terrible!’

She jumped again, as another loud bang reverberated around the square. I’m not happy about this, she thought. I hope we’ll go soon. I don’t like those big bangs at all. She turned to look at Annie, and suddenly forgot about her fears. Annie was staring at something up in the square, Even in the bright light of the fireworks she could see Annie’s pale face, her mouth half-open in shock. She turned to look at Simon. His face was white too, staring in the same direction as Annie.

‘What’s the matter?’ she shouted in Annie’s ear. Annie pointed. Morag looked in the direction to where Annie was pointing. Smoke from the fireworks hung in a heavy cloud above the square. She could smell the sharp taste of gunpowder. Her eyes pricked in the heat and acrid atmosphere. She rubbed them impatiently, and tried to peer through the festoons of smoke thast hung in the dense night air. She saw a stone balcony, jutting out from one of the tall apartment buildings, diagonally across from where they were sitting on the cold steps of the cathedral. It was empty.

‘Annie! Simon! There’s no-one there!’

‘There was! I saw them! Annie shouted vehemently.

‘So did I!’

‘Who?’

‘Doctor Wrist, of course! And all of his family! They were standing there, on that balcony! They were grinning at the crowd below! I don’t think they saw us. I hope not!’

Annie put her head into her hands. Simon moved across and put his arm around her shoulders. Morag stared at them. And then up at the balcony again. It was still empty. A huge bang suddenly made her jump. It was the end of the festa. Despite the remnants of the smoke, she could see people moving in small groups and clusters, still chattering and laughing, towards the main gate. It was all over for another year.

The Airbus banked slightly, and then headed out across the Mediterranean towards the mainland of Europe. Contained within the steel and aluminium tube of its fuselage, Simon, Annie and Morag sat side by side. Their parents were in double seats opposite. Morag lay with her head against the window, her sunglasses slightly askew on her face. Her eyes were closed. Simon and Annie sat together, looking down at the pad of paper that Simon held on his lap, They glanced across at Morag.

‘Morag seems a bit the worse for wear this morning’. remarked Simon, rather slyly.

‘I heard that’. said Morag out of the corner of her mouth.

She settled back, and then curiosity got the better of her.

‘What’s that you’re reading, Simon?’ settling her sunglasses back on her nose.

‘The last part of my account of the great siege’.

‘I’d like to know that. Only, you’d better read it to me. I’ve got a headache and I’m still full of that smoke from last night.’

Simon looked at Annie. She nodded.

“They have left! They have all gone! I, Vincento Viteschi, write this in the year of our Lord, September the eighth, 1565, We have triumphed! Our forces are even now still sweeping down on the Turk as he withdraws to his ships and galleys! Few of us can believe this day. We heard rumblings and groans throughout the night. We did not know what it meant at first. But at first light, we looked across the slopes in front of us. Nothing remained! Nothing was there! The trenches were empty. We could still see the long ruts of their guns where they had fired so long upon us! We were burnt and deafened. The silence was so vast that at first we could not believe it! The Grand Master ordered the gates to be opened. Wounded as I was, in rags, and still holding my trusty arquebus, that had been my friend for so long, I wandered out, like the others, into the Turk’s position. Great was our joy, despite all our privations. Bodies lay everywhere, rotting and bloated in the sun. We took no heed. I picked up a wonderful richly-worked dagger, that some soldier had cast aside. I have it to this moment. We gave thanks to God for this heaven-sent miracle! I must confess I fell on my knees, and prayed for my dearly beloved friend, Francesco, who though a Spaniard, was a great comrade to me, and who perished at Saint Elmo. Thanks be to God for this day!”

Simon finished reading, and closed his notepad.

‘They were finally relieved in the end’. he said. ‘But it was so close. So close’.

They heard the clatter of the meal and drinks trolley behind them, where the air stewardesses were loading up for the in-flight meal. Their mother and father sat together, asleep, her mother’s head on her father’s shoulder. They were holding each other’s hand. Annie sighed, and spoke aloud.

‘We’re not just fighting a battle, or a siege any more. We’re fighting a war’.

The Airbus drove on steadily,high above the corrugated brown hills of Italy, back towards Gatwick, and their own home in Brighton.

Frank Jackson (21/09/10) Word count - 10925

1. A view in Malta.

2. The hotel in Valletta that Annie so much admired.

3. Saint Paul’s Bay, where they stayed.

4. A street in Mdina

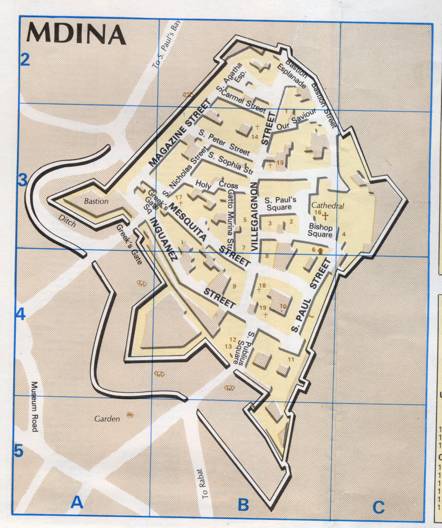

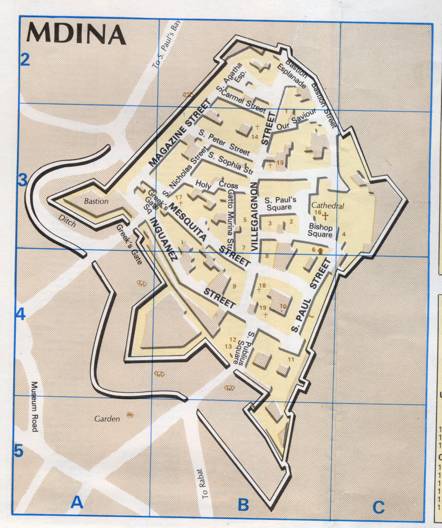

5 Plan of Mdina.

5. An imaginative portrait of Nicolas Flamel as he appeared to a nineteenth century engraver.

|